Page 8. Tuesday, November 29, 1960

They salute Sir Andrew Russell

“New Zealanders owe a great debt to General Russell,’ says a former aide-de-camp in this article.

How he led NZ Division in crisis of 1918 – and closed the gap

AFTER the battle of Passchendaele in October 1917 the New Zealand Division was for a time out of the line preparing, after its rather heavy casualties suffered in that epic effort, to go into a sector of the Ypres Salient.

I was then with the 3rd Canterbury Battalion. Winter was approaching and the prospect of months in the trenches was not a very cheering one.

Out the blue as it were, a message came to me, a command that I was to present myself at General Russell’s headquarters.

Not knowing the reason for the summons I was a little apprehensive on my way to meet the General. The little world of a platoon commander or that of a temporary company commander is in quite a different sphere from the realm of Divisional Headquarters.

I knew little of the division’s composition or personnel. Certainly in Armentieres, when a Parliamentary delegation visited us and Sir James Carroll spent some time with the Maori Battalion and Mr Parr was under my charge to visit the Second Auckland Battalion in the trenches, General Russell had invited Lieutenant Downie Stewart and me to dinner as guests with our fellow Members of Parliament. That is all I knew or saw of Divisional Headquarters.

However, when I presented myself to General Russell the interview was short and to the point. He smilingly said he wanted me for a time to be an aide-de-camp, and when I was a little perplexed he said: “You’ll be sure of dry quarters for the winter.”

That settled it.

No. 1 Mess

Divisional Headquarters for that period when the division was in that area was Anzac Camp. General Russell and his immediate staff messed in a Nissen hut known as No. 1 Mess.

The members of that mess were the General; Staff Officer Colonel Wilson , better known in the Second World War as Field Marshall Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, Commander-in-Chief of the Middle East and now Lord Wilson; Colonel Reid of the British Army, head of “Q” Service Quartermaster-General and generally known as “Red Reid”; Prince Leopold de ? of Belgium attached to the New Zealand Division while the division was in Belgian territory; Mr Malcolm Ross the New Zealand war correspondent; Captain Dick Riddiford of the Wellington Regiment, ADC; and myself.

This group of men General Russell called his family and laid down a strict rule that at mess rank vanished and all seven officers were equal.

“Up the line”

As soon as the division took possession of its sector – the Ypres sector – I soon learned what life at Divisional Headquarters meant. In separate huts staff officers worked all day and far into the night on maps and reports from different units.

General Russell’s work commenced in the very early morning. It was my duty to accompany him “up the line” where he kept in personal touch with brigade and battalion headquarters – insisting on seeing for himself and leaving nothing to chance.

In those grim black freezingly cold mornings before dawn in the winter of 1917-1918 the General would have a snack for breakfast, the dim hut illuminated by kerosene lamplight and then a car would rumble and take us over the rough road through the ruined town of Ypres and up the Menin Road. The car would stop – that was as far as any vehicle could safely proceed.

Out of the car the General would lightly step on to duckboards with a swinging stride with the buoyancy of a young athlete with an untiring gait.

At the Butte headquarters he would confer with the brigadier-general who was for the time being making his headquarters in that queer pyramid of a place The conference over, off he would tramp on to see if and how new trenches were constructed in the front line.

Talked to men

On the return journey he might meet an officer belonging to a unit and question him on his work. A private would be stopped and the General would talk with him not merely to pass the time of day but to learn from the private if he intelligently understood his platoon’s position and the job his unit were committed to.

The Operation Polderhoek was undertaken by a selected unit from the division and this project caused daily visits to the region involved and to the place where the force selected for this assault was in training.

Staff work at headquarters involved headquarters in long hours of work – intensive work by day and later hours at night. After General Russell’s visit to the sector in the early mornings he had his afternoon filled with work – visiting units in training, interviewing senior officers, at dinner a senior officer or two as guests, and then work, more work, in his office until late in the night. He certainly lived and worked in top gear.

Health suffered

The winter of 1917-1918 in that damp region of Flanders was a very severe one. Repeated colds and pleurisy affected General Russell. The doctors ordered him away from the marshes and fogs and mists of Flanders to the sunny south of France.

The let-up and this change worked wonders in the General for he returned and quite recovered in health and ready to pay due attention and courtesy to these important guests.

The United States of America had at long last decided to join the Allies and in America the armies of the United States were in training. Before the armies of the United States landed in France it was deemed expedient that senior officers should visit the front five units of the Allies and see for themselves what we were up against. So it came about that General Russell had as his guests for some weeks three United States officers.

Major-General Hodges was a highly-thought-of American officer, famous for his knowledge of engineering. He was accompanied by a staff officer who was taken in charge by Colonel Wilson. His aide, handsome Captain William Cowgill, was handed over to Captain Riddiford and me.

War school

These officers received a thorough schooling in modern warfare, General Russell not sparing himself to convey to his protege details that would help him when his division set foot in France and Flanders.

Other distinguished visitors to General Russell’s mess were the two Bourbon Parma princes – the elder a claimant to the Kingdom of France; these officers served with the Belgian not the French army.

There were frequent visits of high-ranking officers to General Russell at different times and, of course, visits of General Russell to other units.

I remember especially a visit General Russell paid to the Australian headquarters of Major-General Monash. These two generals had fought together at Gallipoli and a very understanding and cordial friendship was the result.

Discussing books

It was amazing to me how General Russell, leading this strenuous life, could find time to keep himself abreast with important current literature. He must have read until the small hours of the morning after his long day’s work was done.

I had to seize snatches of time during off-duty time to keep my reading up-to-date; for from military worries and work he sought diversion in discussing recent books and literature. He was educated at Harrow, Winston Churchill’s old school, and certainly had a very good grounding in classics.

French was a subject he was particularly fond of, and to perfect his accent when he was at school in England he went for walking tours in France, speaking and hearing French spoken the while. He had a distinguished career at Sandhurst and saw military service in India.

In New Zealand he served with the Fourth Wellington East Coast Mounted and in 1911 he was a brigade commander. With the New Zealand Forces in Gallipoli he was General Officer Commanding a mounted brigade. On forming our forces in 1915 at Moascar in Egypt after Gallipoli into a division he was General Officer in Charge and held that position until the war finished in 1919.

Wounded

At Messines he was wounded but returned in duty. In 1917 he reserved the honour of Commander of the Bath.

His foreign honours were Legion of Honour by France, Croix de Guerre by Belgium, Order of Danilo by Montenegro. He was also a Commander of the Order of Leopold (Belgium) and a Commander of the Order of White Eagle (Serbia).

His British honours were Knight Commander of the Bath in 1917 and in 1915 the honour of Knight Commander of Saint Michael and Saint George.

In April 1918 the situation in France was serious for the Allies. The Germans had broken through and down on the old Somme area near the town of Albert – there was a gap of three miles in our British line – and the way clear for a straight drive through to Paris.

At this crisis the New Zealand Division was hurried down to this gap and the honour of holding the Hun was in the hands of the 62nd British Division, the First Australian Division and the New Zealand Division.

I had rejoined the third Canterbury Battalion at this time, and I could only imagine what the strain and the anxiety at headquarters must have been.

The gap was filled – the Hun was held and there the Division held its line until the great, the triumphant advance some months later.

Message

On a memorable Easter Monday in 1918 I received a message from Brigadier-General Young to report to him. I did so – General Young informed me that General Russell had sent for me. I duly reported to my General and received from him the appointment of divisional representative in America of Lord Beaverbrook’s mission.

“You are on duty,” the General said to me at his headquarters. “So we shall ride together to the conference of the generals of the Australian and 62nd British Divisions.”

I was back with “the family” again and received their congratulations and the injunction from the General what I was to do and to report on this important mission.

Great debt

We owe in New Zealand a great debt to General Russell. As General Officer Commanding the division it is difficult to assess what his leadership meant to us. What he saved us, what he did for us, can never be measured.

That he was offered a higher command than the GOC New Zealand Division there is no doubt. He would not leave his fellow New Zealanders.

In 1934 I visited England. Sir Andrew Russell insisted I get in touch? in England with Lord Wilson, the former Jumbo Wilson, General Staff Officer New Zealand Division, which I reluctantly did. I felt after so many years since we were together in Flanders – and knowing what very important posts such as Field Marshall, Commander-in-Chief of the Middle East he had occupied – a little surprised that he wanted to see me.

We met in London by appointment. He talked of General Russell and said “He was the best general I ever served under.” Could any praise have been higher?

Then Lord Wilson talked of the tragedy of General Russell’s son John, who was killed in the Middle East. The sympathy of one of “the family” for his old chief was very sincere. He had a high regard for the young officer who was following in his father’s footsteps.

RSA leader

Sir Andrew’s interest in the New Zealand soldier did not cease when he was placed on the retired list of the New Zealand Military Forces, for from 1920-1924 and from 1926 until 1935 he was president of the New Zealand Returned Services Association.

One year he led a delegation from the New Zealand association to Australia when the Duke of Gloucester met the Anzacs in Melbourne. When the Second World War struck us once more his services were offered, and he became Inspector-General of the New Zealand forces with headquarters in Wellington.

As a Member of Parliament myself I regretted that Sir Andrew’s ability and his knowledge of military matters, his skill as a speaker, were not availed of in the halls of the legislature. As a Member of the Upper House, as it was then constituted, his services would have been of inestimable value to the country.

Memories

I shall cherish memories of those happy months I spent with “the General.” As a soldier – a scholar – he was indeed in a very high class. He was a valued friend.

As a host, he and Lady Russell added to their cheery friendly welcome at their home, Tunanui [Tuna Nui], a charm and graciousness which cannot be forgotten. He loved his farm, his trees, his stock.

He loved New Zealand and New Zealanders. He served his country well. His long illness he suffered with courage and patience and every cheerfulness. Now he has gone and I say “goodbye” to a valued friend.

May I borrow from Shakespeare, the poet, whose works he knew and appreciated so thoroughly these few words of farewell:

“Goodnight – and flights of angels waft thee to thy rest.”

Old soldiers recall service with general

Throughout Hawke’s Bay, many old soldiers who served with the late Major-General Sir Andrew Russell have expressed sorrow at his death.

Mr Harry Lomas, 618 St Aubyn Street, Hastings, one-time driver to Sir Andrew said today: “He was a great soldier, a gentleman, and he never said anything he did not mean.”

Mr Lomas had many encounters with Sir Andrew in his later years.

His wish

“I had to go and present a replacement of his gold RSA badge to Sir Andrew about three years ago when the original was lost,” he said “and on that occasion Sir Andrew, who was approaching 89, said his one ambition was to live to 90, like his friend Lord Bledisloe.

“I’m glad he got his wish.”

Mr Lomas first met Sir Andrew in 1911 when he was in command of a Mounted Rifles camp at Tutira.

“Later when I worked at the Hawke’s Bay Farmers’ garage in Hastings, I used sometimes to serve him with petrol. He drove his own car till he was 85, and was a good driver.”

Mr Lomas often acted as driver for Sir Andrew in France, and also in civilian life.

“The last time was for the laying of the foundation stone of the Hastings Memorial Library. I remember him refusing assistance to ascend the stairs to the Mayor’s room after the show, saying that if he couldn’t make it on his own power he wouldn’t go at all – but he got there.

Ex-groom

Mr William O’Neill, owner of the Crown and Union Hotels, Napier was Sir Andrew Russell’s groom during the First World War and before the war acted as his chauffeur and horse breaker.

Mr O’Neill, now 81, was born in County Waterford, Ireland, and recently suffered a stroke. He does not recall[?] very clearly as far back as the First World War, but one memory of the time remains with him.

The general was a stern disciplinarian, but never lost his humanity.” he said. “I can remember when he was promoted. He recalled a parade on Lemnos Island, and told the men that he had got his promotion because of the performance by the men, and he owed it to them.

“He also said that he might have been a bit hard on them, but would turn over a new leaf. But he was never hard on me.

“At times he was very much the British officer, but it didn’t take him much to forget it. He was always one for the men, and would stand by them in any trouble.

Courage

“He was a courageous man, and I remember him on the peninsula (Gallipoli) standing up in a trench. The men said, “Don’t stand up there sir, you’ll get hit.” And he’d no sooner said “Don’t worry they won’t get me,” when a bullet went straight through his steel helmet.

“He was in hospital for only 24 hours, then insisted on coming back to be with his men.

“Oh, yes, he was a professional soldier, and in love with his job, but he never lost sight of the fact that the men came first,” said Mr O’Neill.

Tireless soldier – no dugout king

THE DEATH of Major-General Sir Andrew Hamilton Russell, KCB, KCMG, at the ripe old age of 92 years has removed to higher service one of our most distinguished military leaders.

Every Digger who served with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade in Egypt and Gallipoli in 1914-1915, or in Egypt, France, Flanders and Germany 1916-1919, under his command, will mourn his passing.

So too will the thousands of ex-servicemen who remember his great service to their cause and welfare in the early days of the New Zealand Returned Services Association, when, as it’s president, he led the team who laid the foundations for much of what we now enjoy.

Truly “Old soldiers never die – they simply fade away.” Sir Andrew has faded away, but memory of him will not fade while any two of us remain unfaded, who were privileged to serve under him and can foregather as old Diggers do.

He formed, trained and led to victory the New Zealand Division acknowledged by both friend and foe, to be one of the four best divisions among the armies in France, be they allied or enemy. It earned the name the Silent Division because it did its job without fuss or bother, successfully and well taking its cue from its commander.

He commanded, from its launch in 1916, to its disbandment in 1919, without break, what was indeed a happy division, because he saw to it that it was so. Discipline was maintained completely because of his ability to interpret situations sensibly.

Inspiring

No “dugout king”, he wore out a long succession of ADC’s by his visits to the front line, where the sight of him was always welcome and inspiring to his men, particularly when things were tough.

He was the native-born commander of our first complete fighting unit, a full division of 20,000 men and all arms of the service, all from New Zealand. With it, our Dominion won its spurs in battle and graduated to nationhood.

Our nation owes him much – more, indeed, than it has yet acknowledged fully.

That he could be the great leader that he was is not altogether to be wondered at. He came of a military family with a fine tradition.

His great-grandfather, Captain Andrew Hamilton Russell of the 28th Regiment, fought at the Battle of Copenhagen, took part in the Walcheren Expedition and was killed in action in the Peninsula Campaign in 1811.

His grandfather, Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew Hamilton Russell commanded the 58th Regiment in New Zealand during the Maori Wars.

His father Captain Andrew Russell served with the British Army.

His uncle, the late Sir William Russell, KB, was educated at Sandhurst and commissioned in the 58th Regiment, which he joined in New Zealand. Retiring from the Army in 1862, he settled in Hawke’s Bay and served for some years as captain of the Meeanee Militia. The Hawke’s Bay Rifle Volunteers were enlisted on June 6, 1867 under his command as captain.

In Parliament

He represented Hawke’s Bay in Parliament for over 21 years. For six years was the Leader of the Opposition, and in 1854 was Postmaster-General. From 1883 to 1891 he held the Portfolios 0f Colonial Secretary and Minister of Defence.

He lost one son killed in action while serving in South Africa. Another of his sons was commissioned in the 38th Regiment.

Sir Andrew’s military career began at Sandhurst in 1887, where in his year, he won a sword of honour. Commissioned in the Border Regiment to New Zealand and civilian life he was elected to command the Hawke’s Bay Mounted Riffles on the formation of that Volunteer unit in 1900.

He served as a Volunteer and as a Territorial officer until his appointment, with the rank of colonel, to command the New Zealand Mounted Riffle Brigade, on August 5, 1914. He was promoted to major-general in November, 1915. After service with his Brigade in Egypt and on Gallipoli, he was appointed to form and command the New Zealand Division.

On return to civil life and to his farm at Tunanui he immediately interested himself in the welfare of ex-servicemen.

His greeting to ex-officers of his division was invariably to ask “What are you doing for the returned soldier?” This was followed by the exhortation. “You had the privilege of commanding men overseas now it is your duty to look after them on their return to civil life.” Certainly he practised what he preached.

Return to duty

When the Second World War broke he had already reached the allotted span but returned to duty with the Army in a consultative capacity. His son, Lieutenant Colonel John Tinsley Russell, was killed in action while commanding the 22nd Battalion, 2 NZEF.

It was written of the late Sir William Russell: “He might quite appropriately be called the ‘Bayard of New Zealand Politics’, in the arena of which he fought for many years, yet never once struck an opponent beneath the belt, paltered with his own conscience or did anything unworthy of a gentleman – a man of courtesy and honour.”

If the reference to “politics” be changed to that of “service to his country, and to his fellow men, as a great and brave commander in the field, and a distinguished leader out of it,” the same, and more could honestly be written of Sir Andrew.

He has gone and we shall miss him.

Let’s give him a soldier’s farewell:

“He was a good bloke! – but it may be my turn tonight.”

A former aide-de-camp of General Russell’s, Captain T. E. Y. Seddon, contributes this recollection of the General. Captain Seddon, son of Richard Seddon, the noted New Zealand Premier, was for many years MP for Westland. For 30 years he has been chairman of the War Pensions Board.

Major-General Sir Andrew Hamilton Russell, famous New Zealand soldier, died this morning. See page 10.

This tribute to Sir Andrew Russell is contributed by Colonel Reg Gambrill, VD.

Colonel Gambrill, who lives at Gisborne, served under General Russell in the 1914-1918 war as an officer in the Wellington Regiment attaining the rank of major. He is a well-known barrister and solicitor with a distinguished record of more than 46 years’ continuous military service, in the Volunteer, Territorial and Expeditionary forces. He was for several years honarary [honorary] Colonel of the Hawke’s Bay Regiment.

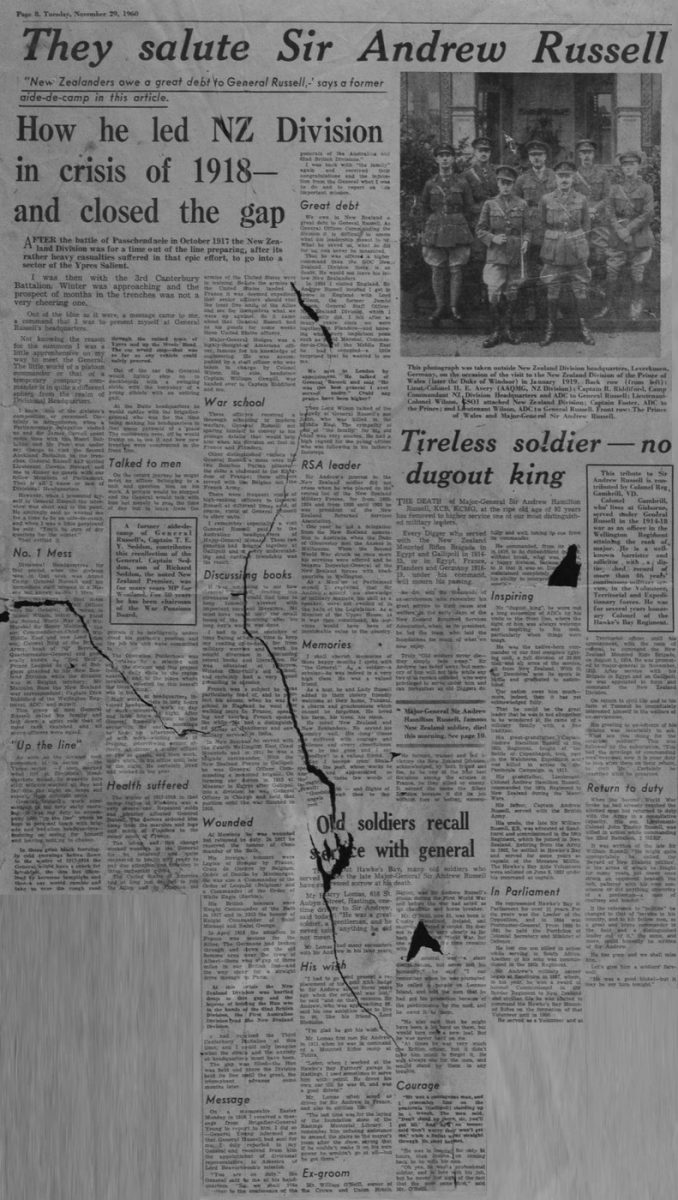

Photo caption –

This photograph was taken outside New Zealand Division headquarters, Leverkusen, Germany, on the occasion of the visit to the New Zealand Division of the Prince of Wales (later the Duke of Windsor) in January 1919. Back row (from left): Lieut.-Colonel H.E. Avery (AAQMG, NZ Division); Captain R. Riddiford, Camp Commandant NZ Division Headquarters and ADC to General Russell; Lieutenant-Colonel Wilson, CSO1 attached New Zealand Division; Captain Foster, ADC to the Prince; and Lieutenant Wilson, ADC to General Russell. Front row: The Prince of Wales and Major-General Sir Andrew Russell.

[HB Knowledge Bank – error in photo caption as Lieutenant Wilson is depicted twice]

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.