- Home

- Collections

- MOODY M

- Newspaper Articles

- Newspaper Article 1988 - Heretaunga land deal fair?

Newspaper Article 1988 – Heretaunga land deal fair?

Heretaunga land deal fair?

Historians Kay Mooney in her History of the County of Hawke’s Bay, Mary Boyd in her City of the Plains and Patrick Parsons in the Herald Tribune’s special centenary of Hastings supplement, have all dealt effectively with the purchase of the Heretaunga Plains and the transactions by which it was acquired by Europeans last century.

This article in three parts is an attempt to examine in more detail the evidence given before the Hawke’s Bay Native Lands Alienation Commission in 1973, to comment upon it, to trace the background for the four commissioners, two pakeha and two Maori, and finally to assess the commission’s findings.

By S.W. GRANT

After the Land Wars between Maori and pakeha in the late 1850s and the early 1860s the Maori will to resist was broken. In the words of the historian, Sinclair, “the Land Court then quietly separated them from their lands.”

The Native Lands Act 1862 waived the Crown’s right of pre-emption over Maori land and was followed by the Native Lands Act 1865 which set up the Native Land Court… “for the investigation of titles of persons to native lands for the determination of the succession of natives to native lands…”

Floodgates open

The floodgates were opened. Clause XXIII of the 1865 Act made provision for the issue of a certificate of title “to be made and issued which certificate shall specify the names of the persons or the tribe who according to native custom own or are interested in the land… provided that no certificate shall be ordered to more than ten persons…”

The theory behind this clause in the Act of 1865 appears to have been that it would be too difficult to locate all those who had a claim to a specified area of native land, that to name ten owners was sufficient, and that those ten would naturally look after the interests of all members of the hapu.

Illegal leasing

The Ngati Kahungunu of Heretaunga soon became aware that covetous pakeha eyes were upon their land and had leased some of it to the newcomers, who were grazing their sheep on the drier parts.

Under an Ordinance of New Zealand entitled the Native Land Purchase Ordinance this arrangement between the Maori owners and the pakeha graziers was illegal.

Occasionally legal action was taken against the lessees but the law was widely ignored. Among the offending pakeha grazing sheep on parts of Heretaunga were the Reverend Samuel Williams and Mr J.D. Ormond.

Oral arrangements

These leases were made by oral arrangement and suited both parties for the time being; the Maori was not averse to receiving money or goods for what he believed to be the temporary use of his land, while even at this stage some of the pakeha had in mind the prospect of buying Heretaunga outright.

As soon as the Native Land Court was established applications were made in many parts of New Zealand for certificates of title.

A series of meetings were held to determine the lawful owners of land. In the court lengthy evidence concerning Maori tribal history, customs, and whakapapa was heard, much of it contradictory.

Ten grantees

On March 15, 1866, the people of Heretaunga made their application for a certificate of title to their land, which was to become known as the Heretaunga block. The block, containing 19,385 acres had been surveyed as the Act required by Mr William Ellison and was bounded on the south and east by the Ngaruroro River, on the north by the Ohiwia River, and on the west the the Waitio River.

Most, but not all, gave evidence in the court presided over by Judge T.H. Smith and two Maori assessors, Te Kune and Te Hemara, as to their ancestry and their claims to be owners of Heretaunga.

Eventually a Crown grant of the land was made by the court to ten grantees. During the course of the hearing much interesting tribal history, some of it conflicting, was heard, but by December 1866, final agreement among the Maori owners was reached, the court ordering that a certificate of title should be issued to the following as owners of Heretaunga:

Henare Tomoana

Arihi

Manaena Tini

Matiaha Kuhukuhu

Paramena Oneone

Apera Pahoro

Karaitiana Takamoana

Te Waka Kawatini

Noa Huke

Tareha Moananui

During his evidence given to the Native Land Court Karaitiana Takamoana admitted that he had been leasing land to the pakeha since 1857.

One of the illegal lessees was Mr Thomas Tanner, who emigrated to New Zealand in 1849 and first became aware of the possibilities of transforming Heretaunga into fertile land in the early 1860s.

Lead by Tanner

Mr Tanner was to become the very active leader of a group of pakeha whose aim it was to buy the land from the Maori owners and transform the swamps of the plains by draining and irrigating it into good grassland.

To carry his schemes into effect would require the expenditure of capital, of which he was himself possessed, as were the men he persuaded to join him in his projects.

Those whom Mr Tanner first approached were the Reverend Samuel Williams, Captain J.G. Gordon, Mr J.B. Braithwaite, Captain A.H. Russell, and Mr Purvis Russell.

Except for Mr Braithwaite, who was a bank manager, all were landowners possessed of considerable capital.

The Reverend Samuel Williams asked that his share in the consortium should be taken by his brother-in-law Mr J.N. Williams, and Mr J.D. Ormond, a member of the Hawke’s Bay Provincial Council, wrote to Mr Tanner asking to take up a share.

Eventually the shares in the leasehold were held in the following proportions: Tanner (3), J.N. Williams (2), Captain A.H. Russell (2), Captain J.G. Gordon (2), J.D. Ormond (1), Purvis Russell (1), J.B. Braithwaite (1).

Thus these seven men held 12 shares among them.

As the purchasers became the subject of some notoriety they were cynically dubbed ‘the Twelve Apostles.’ No doubt the part played by the missionary’s son, Mr Samuel Williams, was the inspiration for the apostolic title.

River change

In pre-pakeha days the Ngaruroro River must have changed its course many times, but when the pakeha arrived in the late 1840s and the early 1850s, the river was on a fairly steady course swinging south from what is now Fernhill, along the south and west sides of the present Hastings to Havelock (founded 1860), and then turning north to flow out to sea near Clive.

In 1867 a great flood occurred which altered the course of the river very considerably. After the 1867 flood and another in 1870, the Ngaruroro established its bed well west of its former course running through Fernhill in an easterly direction to the sea.

This change of course had a dramatic effect upon the Heretaunga Plains, draining much of the water from the area now occupied by Hastings and its surroundings. The land became even more desirable in the eyes of the pakeha buyers.

First had come the Native Land Court order vesting the Heretaunga block in the names of ten grantees; now a heaven-sent change in the course of the Ngaruroro, improving the drainage of the plains substantially.

Sold by 1870

By 1870 the Heretaunga block, with the exception of a portion known as the Karamu Reserve containing 1500 acres, had been sold.

Mr Tanner acquired by far the largest share amounting to nearly 6000 acres, or a third of the block, comprising the greater part of the land now occupied by the city of Hastings; Mr J.N. Williams had Frimley; Mr A.H. Russell and his brother Captain W.R. Russell had Flaxmere; Mr J.D. Ormond took 1250 acres which he named Karamu, although it was not part of the reserve of that name.

Karamu Reserve lay on the east side of Heretaunga covering an area to the south and west of Mangateretere. It suffered the fate of many Native reserves and was cut and sold to individual buyers, both Maori and pakeha.

Sale criticised

In the 1870s New Zealand was still a country of small population but the case of the Heretaunga purchase, when the names of the purchasers and the methods by which the land was acquired became known, aroused widespread criticism in Hawke’s Bay and far beyond and stimulated heated debate and recrimination in the House of Representatives.

The Stafford Ministry, the Government in 1872, took the course common to governments when they are confronted with questions which are difficult to answer: It set up a Commission of Enquiry to investigate the sale of native lands in Hawke’s Bay and to report its findings to the Government.

The required legislation was passed under the title of The Hawke’s Bay Native Lands Alienation Commission Act 1872.

Four appointees

Four commissioners were appointed, two of whom were pakeha and two Maori. The former were Mr C.W. Richmond, at the time a Judge of the Supreme Court of New Zealand, and Mr F.E. Maning, a Judge of the Native Land Court. The Maori commissioners were Wiremu Te Wheoro te Morehu Waipapa and Wiremu Hikairo.

It is from the published reports of the Alienation Commission as presented to Parliament, including as they do the evidence given by both pakeha purchasers and Maori sellers, that the details of the transactions occurring can be learned.

Following the conclusion of the evidence come the opinions of the commissioners expressed in their individual reports on the proceedings of the buyers and sellers not only of Heretaunga, which was by far the largest sale investigated, but also in a number of smaller areas of land.

Our next instalments will describe the methods used by the purchasers of Heretaunga to persuade the ten grantees to sell their shares of Heretaunga.

Photo captions –

Mr Tanner…an early lessee from the Maori and the man who had the first choice of the Heretaunga carve-up. He chose the eastern side of present-day Hastings, eventually being master of 5600 acres.

Sir William Russell…one of the apostles

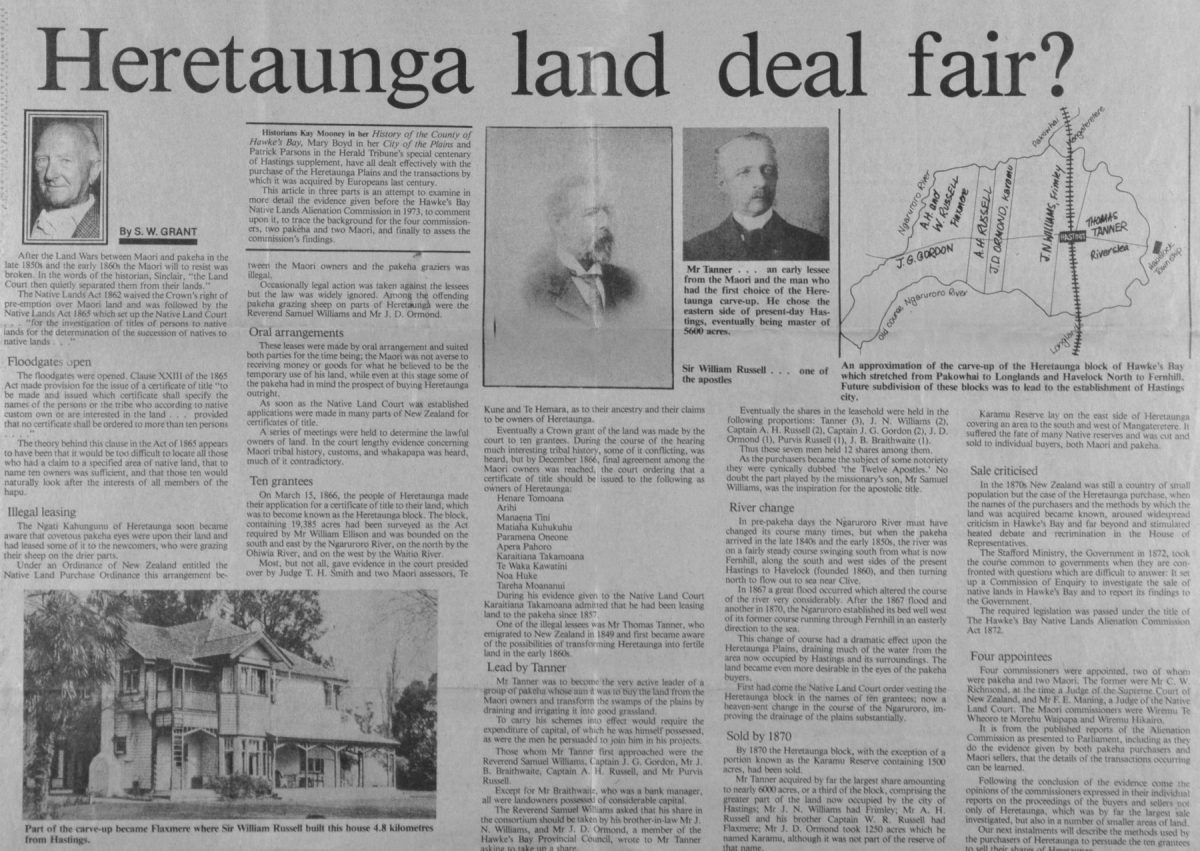

An approximation of the carve-up of the Heretaunga block of Hawke’s Bay which stretched from Pakowhai to Longlands and Havelock North to Fernhill. Future subdivision of these blocks was to lead to the establishment of Hastings city.

Part of the carve-up became Flaxmere where Sir William Russell built this house 4.8 kilometres from Hastings.

Maoris pay debts with land

By S.W. GRANT

This article is the second in a three-part series which attempts to examine in detail the evidence given before the Hawke’s Bay Native Lands Alienation Commission in 1873, to comment on it, to trace the background of the four commissioners and to assess the commissioners’ findings.

In the first of the series last Saturday the writer told of the period after the land wars of the 1850s and early 1860s when the Native Land Court was set up “for the investigation of titles of persons to native land for the determination of the succession of natives to native lands.”

It can be said from the outset, without contradiction, that Mr. Thomas Tanner was both the initiator and executor of the purchase of Heretaunga – ‘the chiefest of the apostles’ Mr Richmond called him in a private letter.

The rest of the Apostles were content that it should be so as they had confidence in Mr Tanner’s business ability and know of his influence with the Maori whose language he spoke and understood.

Mr Tanner did not conduct personally all the negotiations to buy, but used the storekeepers and publicans , Mr Frederick Sutton and Mr R.D. Maney, and more than one solicitor but particularly Mr Joshua Cuff, Mr J.N. Wilson, and Mr A.R. Lascelles, all of whom were in practice in Napier.

Finally, he employed the interpreters Messrs H.R. and F.E. Hamlin, both sons of the missionary, the Reverend James Hamlin, who for many years was stationed at Wairoa.

Other licensed interpreters who gave evidence were Mr J. Grindell whom Mr Tanner paid for refraining from interpreting for other pakeha buyers, and Mr G.B. Worgan whose license was revoked by Mr Donald McLean not long after the commission concluded its task.

Mr Frederick Sutton and R.D. Maney played an integral and dubious part in the transactions.

Both these early Hawke’s Bay settlers allowed and encouraged their Maori customers to make extravagant purchases of goods on credit over considerable periods with the result that they incurred large debts which they could not pay.

For example, Te Waka Kawatini, one of the ten grantees, owed Mr R.D. Maney a total of £948 of which £370 or 39 per cent of the bill was for wines and spirits.

Paoro Torotoro (accused of being drunk most of the time) had an account with the same publican amounting to £626 of which £213 was for grog or 34 per cent. Other items included in these two accounts included clothing, tea, flour, tobacco, building materials, and saddlery.

Mr Richmond in his finding commented that these examples were some of the worst of a number of others. Nevertheless, a substantial number of Maori included in this harmful and reckless spending which was eventually to be paid for by the loss of their heritage.

Far from sober

If it is considered that some of them were often far from sober when they were presented with legal documents of management to sell or mortgage (forms which even when explained by interpreters were difficult for them to understand) the iniquity of the proceedings is evident.

In such cases the Maori of Heretaunga were in no condition to exercise any kind of judgment.

When Mr Maney and Mr Sutton estimated that the time was ripe to press for payment they threatened to take legal action which in default of payment would have their Maori debtors imprisoned.

It was easy then for the creditors to say: “Well, you have a share in Heretaunga. Sell that, your debt will be paid, you will not have to go to prison.” Simple terms, easily understood.

Two deplorable examples of this kind of pressure were cited in evidence: In 1869 Henare Tomoana offered the services of a body of 160 local Maori to join the Government forces against Te Kooti and his men near Taupo.

Henare Tomoana owed Mr Frederick Sutton a considerable amount and on the eve of his departure upon the war expedition he was served with a writ tor his arrest.

Pressure tactics

The ‘loyalist’ about to assist the pakeha in a war against the Maori would have been imprisoned had it not been for the invention of Mr Thomas Tanner or Mr J.D. Ormond or both, who apparently assured Mr Sutton that he would receive his money at a more opportune time.

In a second example of pressure tactics the lawyer Mr Joshua Cuff was sent by Mr Tanner to follow Karaitiana to Pakowhai to insist on payment of his debts.

In one pocket Mr Guff had a writ for Karaitiana’s arrest and in the other a knotted handkerchief containing £1000 with which to buy Karaitiana’s land.

The following of Tareha Moananui to Wellington was another example of dubious tactics. The advantage of isolating one grantee from the others were obvious.

Away from his fellow grantees and his own hapu a Maori owner felt less secure, more confused, and was more likely to agree to sell.

In 1869 the Duke of Edinburgh visited New Zealand. Both pakeha and Maori were eager to see the second son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Parliament was in session and Tareha was member for Eastern Maori.

Also in Wellington were Mr Donald McLean and Mr J.D. Ormond, the former Minister of the Crown, the latter a Member of the House of Representatives.

There, too, were the Reverend Samuel Williams, attending a sitting of the Native Land Court, Mr J.N. Williams, Mr Thomas Tanner, Mr R. D. Maney, and the interpreter Mr H.M. Hamlin.

It is probable that all were in the capital city to show their loyalty to the Royal visitor, but if so, some of them combined business with pleasure, pursuing Tareha to a hotel and to Te Aro to urge him to sell his land for £1500 to Mr Thomas Tanner so that he (Tareha) could pay his debts to Mr R. D. Maney and a trader named Mr Peacock.

Tareha ran away to a house in Te Aro, was pursued and brought back to the hotel where he agreed eventually to sign a transfer of his land, the generous creditors buying him a gig, as well as giving him and his wife some cash.

Photo caption – From the railway line looking toward Havelock North in the early 1880s. Mr Frederick Sutton built the Railway Hotel, left the forerunner to the Grand, opening it in 1875, The price of the land was £97.10.

Perjury common at commission hearing

Mr Donald McLean was superintendent of the province of Hawke’s Bay from 1863 to 1869; Mr J.D. Ormond was deputy superintendant from 1865 to 1868 and superintendent from 1869 to 1876.

It is commonly said that the two men ran Hawke’s Bay. There is no direct evidence that either of these two, both substantial landowners themselves, tried to influence the Heretaunga Maori to sell their land.

The imputation that both had used their official positions and political influence to obtain the sale of Heretaunga had been so widely bandied about in Hawke’s Bay and Wellington that both saw fit to write to the Hawke’s Bay Herald before the commission hearing was ended to state categorically that they had in no way used their influence to help gain the Heretaunga land.

The evidence heard by the commission contains some prime, even ludicrous, examples of the tactics used by the would-be buyers and the evasions of the Maori owners.

All the witnesses were sworn in and nearly all denied what was said about them and the bargainings, both Maori and pakeha. That a great deal of perjury was committed is certain.

Prisoner claims

Henare Tomoana told the commission of a meeting with Mr Joshua Cuff, Mr Thomas Tanner, and Mr Hamlin at Waitangi, a mile or two out of Napier.

According to Henare he was virtually imprisoned there by the pakeha in an effort to get him to sell his share of Heretaunga. Both Mr Tanner and Mr Cuff denied that this was so.

Mr Manaera Tini, who was said to weigh as good 20 stone, told of being relentlessly pursued until he was forced to climb a willow tree to hide from the purchasers.

In the course of evidence Mr Tanner asked Manaema “What did you go up the tree for? Manaena replied “ I was tired of your coming and I ran away I was tired of being hunted; they were like bush dogs hunting bush pigs.”

Mr Waka Kawatini replying to a question by the lawyer Mr Sheehan asking whether he was aware how much money he was to get answered ‘No: I was the only person and I was supplied with rum. How could I see?”

Mr J.N. Wilson, another Napier lawyer admitted that Mr Waka was generally not fit to transact business as he was often in liquor. “Two gallons of rum was usually the consideration he wanted for any of his land.”

Mr Apera Oahoro claimed that he was under the influence of alcohol when negotiations over Heretaunga were in progress.

He said the interpreter, Mr James Grindell, met him near Pakipaki and took him to to a public house. Mr Tanner cross-examined Mr Pahoro asking: “ Did you get some drink?” To which Mr Pahoro replied: “Yes, there were twenty persons intoxicated.

“And again later Mr Tanner asked Mr Pahoro: “ Did he (Mr Grindell) take you to Havelock?

“Yes.”

“Had you not some spirits when you got there?”

“Grindell got intoxicated. And I and Paranema returned.”

The evidence given by the Maori owners having concluded, the pakeha buyers and others involved in the transactions then appeared before the commissioners.

Allowed debts

Mr Maney and Mr Sutton, the principal intermediaries between the owners and the buyers, made no attempt to deny that they had allowed the Maori to run up large debts over a considerable period.

Strangely, the commissioners did not ask them why they had permitted such leniency. Mr Maney said that when the land was made over to him in payment for the debts he then transferred it to Mr Tanner because ‘I have always held as a settler of Hawke’s Bay it would be a betrayal to purchase land from a native that I have not given to the occupiers of the land at the same prices as I bought it.”

In the course of his evidence Mr Sutton admitted and commented upon one or two discreditable occurrences, with animadversions on both Maori and pakeha.

He had retained some £700 of Pahoro’s money and when asked why by Mr Sheehan he replied: “He never asked me for it to this day he often came to me for £5 or£10 which I have always given him when he was sober one does not see him sober once in six months.

Never sober

On being asked by Mr Tanner about the percentage of wines and spirits in a debt of £1000 expended by natives and Europeans Mr Sutton replied: “I have no hesitation in saying that as fas as my spirits in a debt of £1000 expended by natives and Europeans Mr Sutton replied: “I have no hesitation in saying that are far as my experience goes there is a larger percentage of spirits with Europeans than with natives?”

Mr Thomas Tanner gave very full evidence and was in the witness box for longer than anyone else.

In his reported evidence there is an excellent description of the Heretaunga Plains as they were when the first pakeha arrived.

It is from Mr Tanner that the more precise details of the transactions are learnt. For him it was obviously fair dealing conducted in the manner used by Europeans over many centuries.

It is Mr Tanner who describes the terms of the final settlement in January 1870, in the office of Mr Joshua Cuff, barrister and solicitor, of Napier, where six of the grantees met Mr Tanner and Mr J.N. Williams and had the Deed of Settlement read to them by the interpreter Mr Martin Hamlin.

Mr J.N. Williams explained the Maori owners that after all their debts had been paid the balance owing to them was £2387.

Karaitiana Takamoana was the first to sign the dead[deed] and was followed by the other grantees.

The Reverend Samuel Williams gave evidence that he was a relative of one of the purchasers of the Heretaunga block, stating “I have an interest in it myself along with Mr James Williams. It is a considerable interest.”

On the next day he appeared again to correct any impression that he was a party to the original lease and stated that he had taken no part in the negotiations of the purchase.

John Davis Ormond, still at this time the superintendent of the province of Hawke’s Bay, gave his evidence in forthright style, stating that he had one share in the Heretaunga block, originally of same 1200 acres, and that he had come in under the lease before the land came under the Native Land Court.

“I have had nothing to do with the negotiations. I have never spoken to a Maori one syllable on the subject from the time the negotiations commenced until they terminated.”

Mr Ormond came under particularly rigorous cross-examination from Mr Sheehan, being asked whether he did not think it part of his public duty as Government agent as well as superintendent to protect the natives from being unfairly dealt with by Europeans.

Mr Ormond’s reply was: “Certainly not. I should not have consented to act had I understood it to be my duty to interfere with their transactions with Europeans.”

After the conclusion of the hearing of the evidence in the Heretaunga case and of the complaints concerning certain other blocks of Maori land in Hawke’s Bay, the Commissioners left to prepare their reports.

The next and final instalment of this article will investigate the backgrounds of the four Commissioners, Maori and pakeha, give a summary of their findings, and comment upon them.

Photo captions –

From the railway line looking toward Havelock North in the early 1880s. Mr Frederick Sutton built the Railway Hotel, left the forerunner to the Grand, opening it in 1875. The price of land was £97.10.

Tareha Te Moananui

Heretaunga land deal ‘unfair’

Realisation came too late

By S.W. GRANT

The third and final article which has examined in detail the evidence given before the Hawke’s Bay Native Lands Alienation Commission in 1873, following the purchase of the Heretaunga Plains by Europeans.

The backgrounds of the two pakeha and two Maori commissioners are traced and the commission’s findings assessed.

Before summarising the findings of the commissioners appointed by the Government to report upon the alienation of Maori land in Hawke’s Bay it is instructive to examine the back-grounds of the two pakeha and two Maori commissioners.

The chairman of the commission was Judge Christopher William Richmond.

It is the convention in English countries to accept that Judges are impartial, incorruptible, uninfluenced (when judging) by their own upbringing and education and remote from the passions which move ordinary men and women.

Judge Richmond was a member of a family who had emigrated to Taranaki in the 1850s and had become allied by marriage to the Atkinson family, the best known of whom was Sir Harry Atkinson who became Prime Minister of New Zealand.

In Pakeha eyes the Atkinsons and the Richmonds were admirable settlers who fought against the Maori of Taranaki for their lands. Their attitude toward the tangata whenua was both aggressive and contemptuous.

Had right to sell

At the time of the historic Waitara dispute Judge Richmond, who was Native Minister, maintained that Te Teira had every right to sell his land without consulting his people whose leader was Wiremu Kingi.

This costly misjudgment was by a later Government admitted as wrong and compensation paid.

It is interesting to record some of Judge Richmond’s comments made at this time and later, which reveal what he really thought of the Maori: ‘A pack of contumacious savages’, ‘ the beastly communism of the pa’, ‘the slough of barbarism from which they are striving to emerge’.

One gains the impression that Judge Richmond was not the man to give a dispassionate judgement about Maori claims.

Judge F.E. Maning, the other pakeha commissioner, was an Irishman who arrived in Hokianga in 1833, lived in that area for a long time and married a local Maori. He acquired a wide knowledge of the Maori, their customs, and lore and was made a Judge of the Native Land Court in 1865.

On the surface it would seem that Judge Maning was just the right man to be appointed to the commission.

Quarrelled with Maori

Unfortunately, at some time before his appointment as a Judge in the Native Land Court he had turned violently anti-Maori and had quarrelled with the local Hokianga people, with his wife, her relations, and his own children.

Through his work for the land court has generally been adjudged of high quality, there is no doubt that he has become an embittered man.

His opinions of people, both Maori and pakeha, at this stage of his life are expressed in virulent form in his personal letters ‘you should see the solid ignorance, pampered, truculent, conceited barbarism, hungering and thirsting after our wealth for themselves, too lazy to create it, envying us, but fortunately, to a certain degree, fearing us.

Pakehas most ill-used

Or this passage from a letter written six weeks after the commission’s hearings had been in progress: ‘I find that it is the pakehas who have been the most ill-used by far and the whole course of the Maori evidence is a mere tissue of exaggeration – prevarication and perjury.

‘The pakehas are also far from angels, but they are chiefly engaged in defaming each other…’

Another letter written after the hearings had concluded: ‘for until you can make until you can make a tiger live on hay you can make nothing of the Maori, but a mean, treacherous, vain, lying and dangerous rowdy, cunning as Satan and dangerous as the serpent – there is only one policy to settle the “difficulty” and that is war a l’outrance’.

An unbiased Commissioner?

How could such a man make an impartial assessment of the evidence?

Co-operation wanted

Commissioner Te Wheoro was a chief of considerable mana among the Waikato Maori and a close friend to Tawhiao.

He favoured co-operation with the pakeha and tried to prevent the young men of the Waikato fighting against them, he himself serving as a captain of militia.

Later he became MHR for Western Maori; he was typical of the good ‘loyalist’, naturally approved by his pakeha employers.

Commissioner Hikairo, the second Maori commissioner as the Ngati wehiwehi and lived a few miles north of Rotorua.

Educated at the mission school conducted by the Reverend Thomas Chapman, Hikairo served as a clerk in the Native Land Court before being appointed as assessor in Auckland. Like most missionary-educated Maori he is likely to have been pakeha-orientated, although little information about him is available.

In spite of the Maori commissioners’ connections with the pakeha it is significant that both dissented from the pakeha commissioners’ findings.

Commissioners’ reports

The heart of Judge Richmond’s report, not just concerning Heretaunga but in reference to all the complaints heard, lies in the following paragraph: ‘Having now gone through the principal heads of imputed fraud, I have to state that, in my opinion, nothing was proved under those heads which ought, in good conscience, invalidate any purchase investigated by us.

I agree with my colleague, Judge Maning, that the natives appear to have been, on the whole, treated fairly by the settlers and dealers of Hawke’s Bay.

I express this opinion as a member of a tribunal, not enabled, nor pretending, to draw legal conclusions.

Some of the stricter principles of an English court of equity may possibly be found to have been infringed upon in transactions examined by us. But it will be difficult for any court to apply ordinary rules in circumstances so peculiar.

To be sure, in a later paragraph the learned Judge does say: ‘Yet I am far from thinking that the Maori of Hawke’s Bay have no real grievances in the matter of their landed rights.’

More forthright

Judge Maning’s findings agreed with Judge Richmond’s, but were expressed in more forthright terms, exhibiting his strong prejudices against the Maori.

The final paragraph of his report reads: ‘The state of things now exhibited in Hawke’s Bay is; I believe, the natural and inevitable consequences of the contact of the two races – one possessed of capital, science, laborious energy, provident, far-sighted, acquisitive and tenacious; the other untaught, in-experienced in the new social conditions which are growing up around him, eager for the present possession of property, devoted to the gratification of the passing day all that can be done is to give the natives a fair opportunity to avail themselves of the benefits of civilisation which are now placed within their reach, and if they abandon or neglect this opportunity to leave them to the event.’

Commissioner Hikairo summed up his finding on the Heretaunga case in brief but telling fashion, making much the same comments as are found in his and Te Wheoro’s general report.

He does not absolve the Maori from all blame for the loss of their land, but makes telling points against the pakeha. Hikairo tabulates his findings as follows:

1. If the Crown grants had been limited to no more than ten persons, much trouble would have been avoided and justice done to all comers.

2. The ten grantees were chosen by the majority of those interested as trustees for them; they were not to sell.

3. Mr Thomas Tanner wanted to get the land for himself and planned to do so when he first obtained a lease.

4. The storekeepers were working for the purchasers of the land and vice versa.

5. The interpreter acted only for the purchasers and the storekeepers.

6. The Maori did not realise the result of amassing debts to the pakeha.

7. The grantees were approached to sell separately.

8. The grantees did not agree that only Henarea [Henare] Tomoana and Karaitiana Takamoana should act for them.

9. The grantees should have met together with the purchasers in one place so that all could have been explained to them.

10. The land is good and the area large, but the price is small.

11. Karaitiana Takamoana, Henare Tomoana, and Manaena did not act fairly by their co-grantees.

Best balanced

Indeed, Hikairo’s report impresses as expressing the best balanced judgment of all the commissioners.

Not only does he list the worst of the pakeha dealings, but also he does not shrink from condemning the foolishness, the ignorance, and most significantly the unfairness of Maori to Maori.

One hundred and twenty years have passed since Heretaunga was first leased to the pakeha and one hundred and thirteen since the Hawke’s Bay Native Lands Alienation Commission investigated the sale of the block.

Nearly all the 19,000 acres have passed forever from the tangata whenua.

Did the transactions constitute a fair deal? In two words Judge Richmond’s finding in relation to the complaints brought before the commission can be summed up – ‘not proven’.

Judge Maning’s findings can be paraphrased as ‘serve them right’. Under English law not one of the purchasers, storekeepers, publicans, lawyers, and interpreters had committed an indictable offence which, if proved, might have made null and void the sale of Heretaunga.

In the minds of many all that is legal is not necessarily ethical. Far from it.

In the case of the Heretaunga purchase there were on the one side the ten grantees and the members of their hapu, most of whom had been brought into contact with the pakeha of Hawke’s Bay not more than fifteen years before the leasing of Heretaunga began.

No education

The Ngati Kahungunu had at this time little or no English education no knowledge of the English language, no understanding of English law, and but a rudimentary understanding of traditional pakeha behaviour.

It is true that they admired the pakeha possessions.

Naturally the Maori coveted the guns, horses, gigs, clothes, alcohol, jewellery, and many other material possessions.

That these desirable things could be bought with money which had to be earned made little impression on the owners of Heretaunga.

Did Ko Tanera work? Did Mr J.D. Ormond? Did the Reverend Samuel Williams?

The facts became obvious to them: The storekeepers would let them buy; Mr Tanner and others gave them money and gifts. The Maori could mortgage (what did that mean?) his land.

Only when they were confronted with their debts and writs did the seriousness of their irresponsibility begin to dawn upon them. Too late, too late.

That the purchase of Heretaunga probably cost the Twelve Apostles dearly – some estimates put the figure at about £20,000, a large sum at that time – is not relevant to the fairness of the deal.

Nor is the fact that the Heretaunga Plains have been transformed into fertile cropping land (upon which, unfortunately, a city has been built) by pakeha brains and hard work, not unaided, however, by the Maori. Reason for assuming that all was fair and above board.

Legal and lay opinion now has concluded that the Treaty of Waitangi has something to do with equity, a quality sadly lacking in the Heretaunga transactions.

A fair deal?

A fair deal? It was a contest between a sophisticated, determined, wealthy group of men, with centuries of commercial tradition behind them and a race already described in Judge Maning’s words ending ‘ leave them to the event.’ In rugby terms, which most New Zealanders understand, as well match the All Blacks with a Te Aute College second fifteen.

There is little that can be done about Heretaunga now, but, to quote Winston Churchill’s words, “the use of recrimination about the past is to enforce effective action for the present.” Much injustice, which can yet be righted, has been done to the Maori in other areas of New Zealand.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Copyright on this material is owned by Hawke's Bay Today and is not available for commercial use without their consent.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Description

Surnames in these articles –

Arihi, Atkinson, Boyd, Braithwaite, Chapman, Cuff, Ellison, Gordon, Grindell, Hamlin, Hikairo, Huke, Kawatini, Kingi, Kuhukuhu, Lascelles, Maney, Maning, Moananui, Mooney, Oahoro, Oneone, Ormond, Pahoro, Parsons, Richmond, Russell, Russell, Sheehan, Sinclair, Smith, Stafford, Sutton, Takamoana, Tanner, Tawhiao, Te Hemara, Te Heira, Te Kune, Tini, Tomoana, Torotoro, Waipapa, Waka, Williams, Wilson, Worgan

Subjects

Format of the original

Newspaper articlesDate published

19 March 1988Creator / Author

Publisher

The Hawke's Bay Herald-TribuneAcknowledgements

Published with permission of Hawke's Bay Today

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.