A gift from the fire gods

By MARION MORRIS

The magic of fire… the blessing of the gods… and the skill of the potter has again triumphed in Hawke’s Bay.

When Bruce and Estelle Martin, Kamaka Pottery, Bridge Pa, opened their anagama kiln after their latest firing the result of the year’s work of their hands and hearts were revealed in all their beauty.

“It’s a bit like being a farmer, being an anagama potter,” said Estelle. “It takes a whole year to see how our work turns out.”

We know only the shape of our pots – it’s what the fire does in colouring and glazing them that is so interesting and beautiful to us.”

Unlike conventional pottery, which is glazed before being fired in an electric, oil or gas-fired kiln, pottery fired in an anagama kiln goes in unglazed and comes out glazed by the ash from the pine wood burned inside the kiln.

“Our pots are painted by the fire but we assist the fire by keeping it awake,” said Estelle.

Ancient method

Anagama is a Japanese word meaning “‘hole kiln”. This method of firing pottery dates back to the 11th and 12th century. Originally anagama kilns were holes dug in clay banks with the flue dug down from a higher level. More modern anagama kilns are built from brick but this method of firing is now rare in Japan because of strict pollution controls and the high cost of wood used in firing.

Pots fired in anagama kilns are unique. During the 10-day firing the ash and flame in the kiln produce natural glazes on the pots that cannot be obtained in any other way. They are all completely individual pots – no two are ever the same.

Bruce and Estelle visited Japan in 1978 and resolved to build an anagama kiln.

It took them three years of part-time digging and laying bricks to build the Kamaka anagama. The main chamber is six metres long, 2.6 metres wide at the widest point and 1.8 metres high.

The floor is stepped in three places. There are no internal supports or dividing walls. Six metres of flue extend from the back of the kiln and a total volume of 47 square metres. The kiln has a main fire at the mouth and three pairs of stoke holes along the side.

Japanese visited

The [In] 1983, Mr Sanyo Fujii, a master Japanese potter and anagama firer, stayed with the Martins for eight months to make pots and participated in the first firing of the Kamaka kiln.

Mr Fujii is still part of Kamaka. Out of respect to him the Martins observe some of the traditions of firing an anagama.

Around the kiln hang paper flying cranes, the symbol of Huneji [Himeji] Castle, an area in Japan, which keep the bad spirits away from the kiln. Small offerings to the kiln gods are of salt (to cleanse) rice (for ancestors) flowers (manuka of New Zealand and pine of Japan) and saki (for the kiln gods).

“We know these things seem strange to most New Zealanders, but we do it out of respect for Mr Fujii from whom we learned so much,” said Estelle.

Firing is always a special time for the Martins. Not only is it the culmination of a year’s potting in itself, the 10 days they spend feeding the kiln has a special peacefulness about them.

“It’s a lovely time – so quiet,” says Estelle.

“Estelle calls it a lesson in patience,” said Bruce.

Peaceful scene

It was a peaceful scene. Soft music came from a transistor radio, a picnic table and chairs sat close by the kiln which, on the second day, was burning quietly and Abbey, the dog, lay asleep at our feet.

The unusually warm May morning smelled of the pine wood stacked neatly in huge piles around the kiln. Inside the kiln, now 24 hours after its lighting, the ash was beginning to form. Outside its entrance down a flight of steps Bruce watched the wood and gently pushed it in further as its ends burned down.

In the 10 days the kiln will be tended day and night the temperature will be coaxed up to 1300C.

The scene will change then.

Feeding the fire will be a more frantic occupation and wood will be put in three areas every five minutes. Bruce and Estelle will be tired but, by then, their two sons will be sharing the firing and all will enjoy the luxury of 12 hours on duty followed by 12 hours off.

Estelle speaks proudly of her five-year-old grand-daughter who last year fed the small wood into the side ports when the temperature was at its maximum.

It was quite brave of Frances to put wood into the glowing kiln,” she said.

The Martins say firing is a time they love. It follow [follows] nine or 10 months of potting then two months of cutting and splitting wood.

Slab pine used

They buy slab pine which has to be stripped of bark and then cut into precise lengths and thicknesses.

“If it is cut too short it burns too quickly and if it is too long it will knock the pots over,” said Bruce.

The thickness varies. The wood for the main front fire has to be thicker and for the side ports it has to be finer and quicker burning to raise temperatures.

Twenty-five tonnes of wood will be consumed by the kiln in the 10-day firing – the Martins think this may equate to 40 cords.

There are other preparations prior to firing. Meals for the 10 days are all ready.

“We have some lovely meals, don’t we Bruce?” said Estelle.

Biscuits and fragrant tea appeared in only a matter of minutes. There is a tent set up nearby with power, a camp bed and the necessities for meals.

The Martin’s house is about 50 yards from the kiln so it is too far away to be used as a base. However, when the 12-hour shifts began they were able to ‘‘go home”’.

This year the Martins were organised early but couldn’t start until their sons were available.

May 2 finally arrived.

“We couldn’t wait for morning to get started,” said Estelle.

That was Wednesday, May 3.

By Friday lunchtime another visit found the Martins still looking fresh and happy with the way things were going.

Intensive heat

The temperature of the kiln was 900C at the front and 800C at the back and wood was now being put through a higher front opening so that it fell on to the ash below and sent it flying upward on to the pots.

It was another warm Hawke’s Bay day and feeding the fire had Estelle sweating. Both have to wear high-necked long sleeved shirts to protect themselves from the heat.

The kiln, covered with a layer of clay, is beginning to expand and small cracks in the clay begin to widen.

The top door of the kiln is kept partially open at this stage so that any carbon is burned off as the long soak (24 hours of gradual temperature rise to heat the back of the kiln and dry the pots) continues.

Bruce says some space-age technology is now part of the kiln.

“We needed a door which we could handle – one that didn’t get too hot as the old iron one did.

“That door is made from silica – the insulation material used in the space shuttle. It never gets too hot to touch despite the 1300C temperature inside the kiln,” he said.

“So we have an 11th century kiln with a 20th century door.”

Expensive

An anagama kiln is an extremely inefficient way to fire pots – expensive and time consuming but the results are outstanding.

Wood as a fuel is remarkable. At the end of the firing the ash of the 40 cords of wood can be carried away in a wheelbarrow.

Day 10 this year didn’t actually arrive.

The Martins decided their pots were ready after nine days and firing ceased.

The unused wood – they estimate they burned only 20 tonnes this year in what they called a lean firing – is part of the reason the Martins now say they will do another firing next year.

They had decided this was to be the last but the leftover wood and the success and excitement of seeing what the fire made them this year has prompted them to fire up again next year.

Moment of truth

Unloading the kiln is another big task in the life of the anagama potter. A year’s pots have to be carefully removed but it’s an exciting time.

Many of the pots – this year many of them are new and original Ikebana containers destined for an international Ikebana conference being held in Christchurch next February – have to be finished by sanding off tiny pieces of silica which are sharp to the touch.

That completed, every piece will be tested for 24 hours to see that it holds water. It will be the end of June before the kiln will be empty and its products on display.

Estelle was thrilled that a small number of pots this year had been given a soft pink and soft apple green colouring.

“We felt that because it was so dry we may have missed out on the full range of colours that an anagama kiln creates but we didn’t.”

She explained that when the ground is moist the kiln seems to attract the moisture which contributes to the pinkish glaze.

10 day cool down

The Martin’s 10-day vigil over their kiln, then the 10-day wait until it was cool enough to open are over and the rhythm of their lives has reached another phase.

For them, and for anyone who has fallen under the spell of their unusual pottery, it’s good knowing that more pots will be made and that the anagama will work its magic once again next year.

Photo captions –

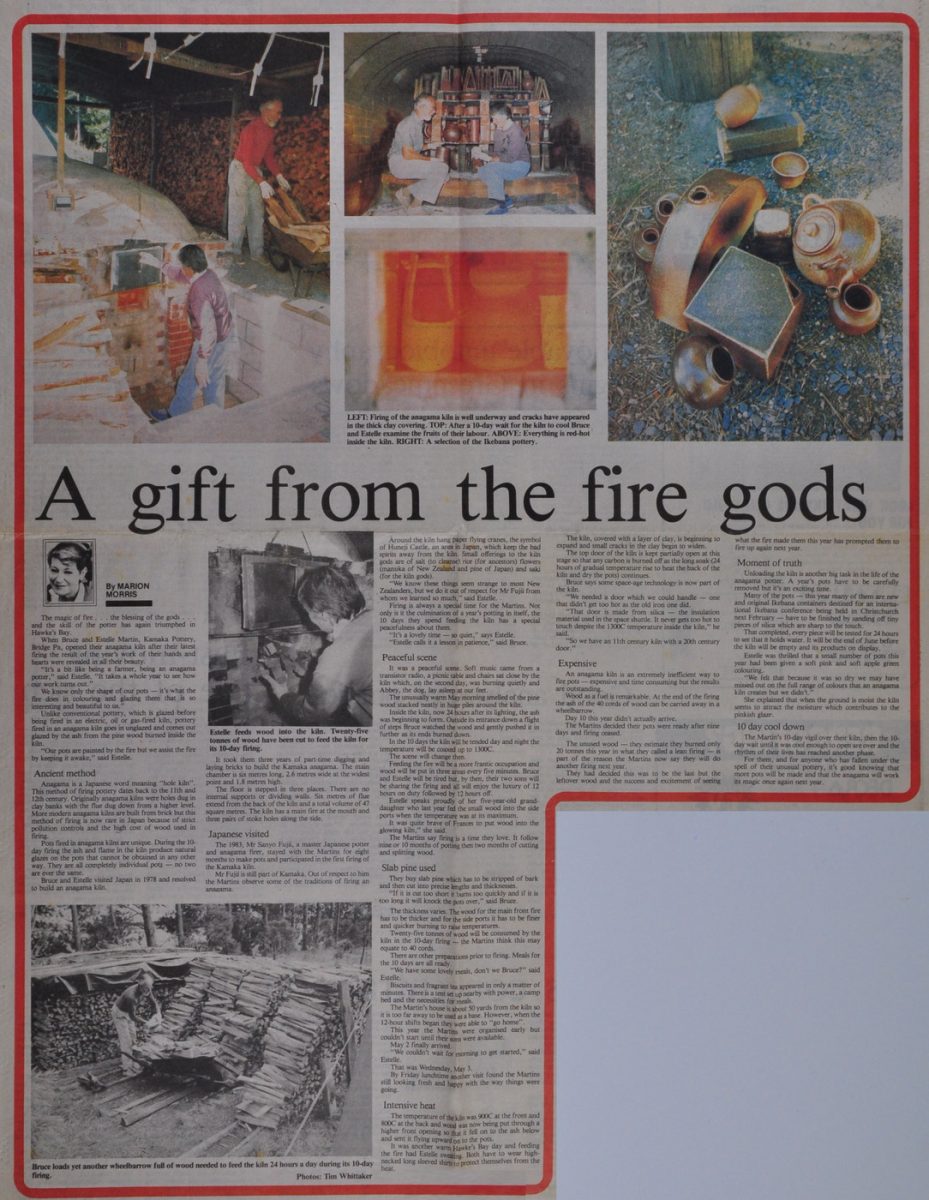

LEFT: Firing of the anagama kiln is well underway and cracks have appeared in the thick clay covering. TOP: After a 10-day wait for the kiln to cool Bruce and Estelle examine the fruits of their labour. ABOVE: Everything is red-hot inside the kiln. RIGHT: A selection of the Ikebana pottery.

Estelle feeds wood into the kiln. Twenty-five tonnes of wood have been cut to feed the kiln for the 10-day firing.

Bruce loads yet another wheelbarrow full of wood needed to feed the kiln 24 hours a day during it’s 10-day firing.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.