- Home

- Collections

- TONER A

- Newspaper Supplement - A Province Reborn

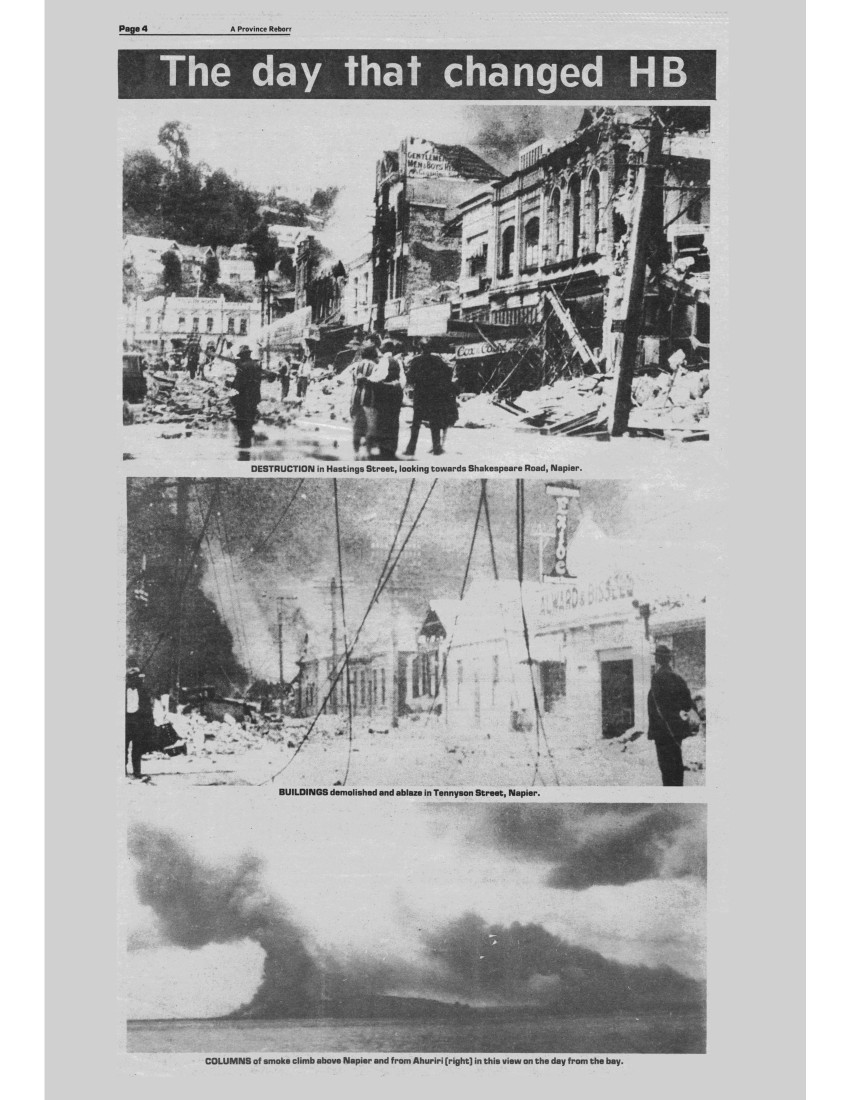

Newspaper Supplement – A Province Reborn

Page 2 A Province Reborn

A Province Reborn

A special issue to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the earthquake which caused widespread devastation in Hawke’s Bay on February 3, 1931.

Published by the Daily Telegraph, Napier, Monday, February 2, 1981.

Fifty years onwards

By Sir Peter Tait

Disaster brings courage; adversity brings challenge; suffering brings strength. These are the attributes found in those people who went through the earthquake. Personal courage was so often displayed.

The citizens accepted the challenge to rebuild; the people became stronger through their suffering.

Napier was faced with the immense problem of re-building their town. This entailed not only their homes and businesses, but providing the essential services of water, sewerage, roading and flood control.

The first decade to 1940 saw many homes and business concerns rebuilt. Planning to utilise some of the 9000 acres of land raised up from the sea started and the first few houses were built in Kennedy Road across Georges Drive. Work proceeded slowly throughout the war years but the suburb of Marewa took shape and housing commenced by the State and the borough.

The Napier Harbour Board received ownership of the 9000 acres of land, and they entered into an agreement with the borough council that the land be planned and developed to cater for residential and industrial use to meet the demand. The co-operation between the board and the town and now the City of Napier has been of immense benefit to both parties. The board has endowment lands and the city has room to expand. They have both grown, side by side.

Suburbs

The early 1950s saw the suburb of Maraenui developed mostly by the Crown, while the City developed the sections of Onekawa and Pirimai. The major problems were those of an adequate sewage disposal system, the provision of a continuous water supply, the provision of sections for both housing and industry, pensioner units for the elderly, and the installation of a flood control system for the low-lying reclaimed areas. A formidable task for any city council.

I had the privilege of being Member of Parliament for Napier in 1951-54 during which time the housing position was desperate. Through the co-operation of the then State Advances and the Minister of Housing we saw more than 300 State houses erected. The Minister warned me this might cost me my seat in the House, but I have no regrets in taking this action. These were some of the problems facing the city council when I became mayor in 1956. I do not wish, in any way, to criticise previous councils – they just did not have the finance to tackle these major problems.

Although Napier is built on underground lakes of clear fresh water, every year hosing restrictions were imposed. The cost of pumping was high and the reticulation and pumping stations quite inadequate. Priority was given to updating the water supply with the result that from 1956 there have been no water restrictions whatsoever imposed in Napier.

A proposition to discharge sewage off the Napier breakwater was quickly thrown out by the new council in 1956. Some 500 acres of land adjoining the Hawke’s Bay Airport was purchased with the view of establishing oxidation ponds and primary treatment. However, after an overseas visit, I recommended this scheme be abandoned as the ponds became popular with gulls and other birds and these would have constituted a flying hazard for the jets using the adjoining airport.

Our advice was that in our geographical situation, a sea outfall system would be the most suitable form of sewage disposal. Under the City Engineer, Mr J. G. Perry, investigations took place at Awatoto to cater for the disposal of sewage for the Napier City and Awatoto industrial area. Float tests at various depths and conditions took place over a number of years and the outfall was finally launched in 1972.

Building

A further problem facing the council was the administration building. The old building on the Marine Parade had served for some 80 years and was in a poor state of repair. Council offices were scattered around the city and after the usual “battle of sites”, a new modern building was erected to house all council departments. This fine building was opened by Sir Keith Holyoake in 1968.

The late Henry Charles was a retired businessman without any close kin. He wanted to use some of his savings for the senior citizens of Napier and offered us the sum of $80,000 providing the council would raise a loan for a similar amount and that it would qualify for a Government subsidy of 1:1. His $80,000 then attracted a total of $320,000 which built 40 modern pensioner units.

The scheme was so popular and the demand so great that Mr Charles contributed a further $80,000 and in addition, sufficient funds to erect a social hall for the occupants of the flats. Shortly afterwards, the Napier District Masonic Trust commenced providing pensioner flats and to date has completed 92 flats. These, together with units build by the State and the city council now total in excess of 600 pensioner units in Napier which would be substantially greater, proportionately, than those in any other city of New Zealand.

New land

The land reclaimed from the earthquake is, of course, low lying, most of it being less than half a metre above sea level. This means that water, sewage and stormwater have to be pumped at considerable expense. The low lying areas have been subjected to flooding problems and this has largely been overcome by the construction of the Purimu Creek with a pumping station capacity of 250,000 gallons per minute. This flood protection was finished in 1972 and completed the major essential services for Napier.

The Municipal Electricity Department has served Napier well and can now boast that 80 per cent of the power lines are underground. It is planned to have the whole of the MED area with underground reticulation within the next 5 years. The MED has also been progressive with its lighting programme using fluorescent tubes for street lighting most effectively. Our MED, under Ray Matthews, was also responsible for installing the flood lighting system in McLean Park of some half a million candle power allowing all varieties of sport to be played at night.

Tourism

Napier has few natural tourist attractions, apart from its glorious weather and we set about building enterprises which would bring tourists to the City. The Hawke’s Bay Aquarium was opened in 1957 under the War Memorial and some four years ago, a new aquarium building up to world standard was opened on the Marine Parade. Marineland has become internationally acknowledged and, together with the aquarium, attracts more than 350,000 people a year and a grand total to the end of 1980 of 5 million visitors.

Councils have been careful to ensure that only worthy attractions be built on the now famous Marine Parade and these have included a fine roller skating rink by the Napier Skating Club largely through the inspiration of Mr Ray Rees; a fine sunken garden named after one of Napier’s greatest philanthropists, Sir Lewis Harris and family; the Kiwi House for the showing of live kiwis, a fine boating lake for children and three now famous sculptures of Pania of the Reef, the Spirit of Napier and, more recently, the lovely sculpture of the fishermen at the aquarium.

Sporting facilities include a modern Olympic swimming pool complex, together with an indoor heated pool, recognised as one of the best in the country. Parks and reserves for all sports have been included as well as a fine Centennial Hall now in the course of extension and the council purchased the racecourse at Greenmeadows from the Napier Park Racing Club. This area is kept as a greenbelt between Napier and Taradale as a good open space of 90 acres.

The success of the manmade attractions in Napier is indicated by the number of tourists now visiting the city which have increased from some 30,000 per year to more than 350,000 per annum.

The boundaries of Napier were extended to include the borough of Taradale after much soul-searching and criticism. It is now acknowledged that the inclusion of Taradale has been of substantial benefit to the city and the borough.

Together with the growth of the city, catering for both industry and housing, the Hawke’s Bay Harbour Board has progressively extended its operations and can justly claim to be the most efficient port of New Zealand.

Gifts

One of the most unusual and interesting exhibits is the Lilliput Village which I had the pleasure of buying and donating to the city. This consists of a completely hand-made model railway with more than 80 animated models and the attraction has been extended by the addition of one of the best solar exhibits in the country.

Mr H. R. Holt donated a magnificent Zeiss Planetarium to the city and under the guidance of our former town clerk, Pat Ryan, a society has been formed to promote the Lilliput Village and feature planetary exploration. This exhibit has attracted almost 100,000 people over the past 10 years.

The last attraction with which I was associated before retiring from the mayoralty in 1974 was to switch on the artificial waterfall at the Centennial Gardens. This area was an old prison quarry where inmates were breaking stones for many years. On one of our visits to our sister city, Victoria, in British Columbia, we saw what had been done at Butchart Gardens, transforming an old quarry into a most beautiful garden setting. Our Reserves Department transformed the quarry and installed an artificial waterfall which is very greatly admired and appreciated.

One of the problems facing tourists to Napier was the lack of reasonable accommodation and here again, the council took the lead by developing the Kennedy Park Motor Camp. The inspiration for its development must go to Mr Gordon Beveridge who has been employed for the past 25 years and, without doubt, it is the most complete camping ground in New Zealand, providing accommodation for tents, cabins, motels and now has a first class restaurant.

Older residents may well recall the battle we had to retain Kennedy Park as a council operation which required special legislation to be passed by the House of Representatives. It involved a great amount of controversy but was successfully concluded.

Space allows only a brief mention of other benefits which have been contributed to the development of our city. The building of the Napier Cathedral, the extensions to the art gallery, the development of Whitmore Park, Maraenui Park, the Botanical Gardens, the development of Westshore, the transformation of many of the original streets on the hill, the building of the senior citizens new hall, are but some of the achievements of the people of Napier.

An example of the generosity of the citizens is shown in the erection of the Princess Alexandra Community Hospital which fulfils a special need in the area and has been responsible in attracting a number of specialist doctors to Napier.

Spirit

Napier has been blessed with an outstanding community spirit which I believe stemmed from the suffering endured during the earthquake. I know of no other city where the spirit of generosity has been indicated in so many practical ways. Almost all of the attractions of the Marine Parade and indeed throughout Napier have been created without any recourse to rates collected by the City Council.

The Memorial Hall, the Floral Clock, Pania of the Reef, the attractions at the Sound Shell, Skating Rink, Sunken Gardens, Marineland and the Aquarium, have all been provided with funds received from the people of Napier. The Olympic Pool complex cost $1m of which only $160,000 was raised by way of loan. Almost every sporting and social club, together with the arts and theatrical societies now have their own club rooms.

Suffering has given our city strength. It has been a privilege to lead Napier as an MP and Mayor for just over 20 years and be a part of an enthusiastic community. Let us continue the example set before us by those who endured the quake.

Not bigger, but better

Not wealth, but perseverance

Not all for one, but all for our City

To leave it a little better

Because we have lived there.

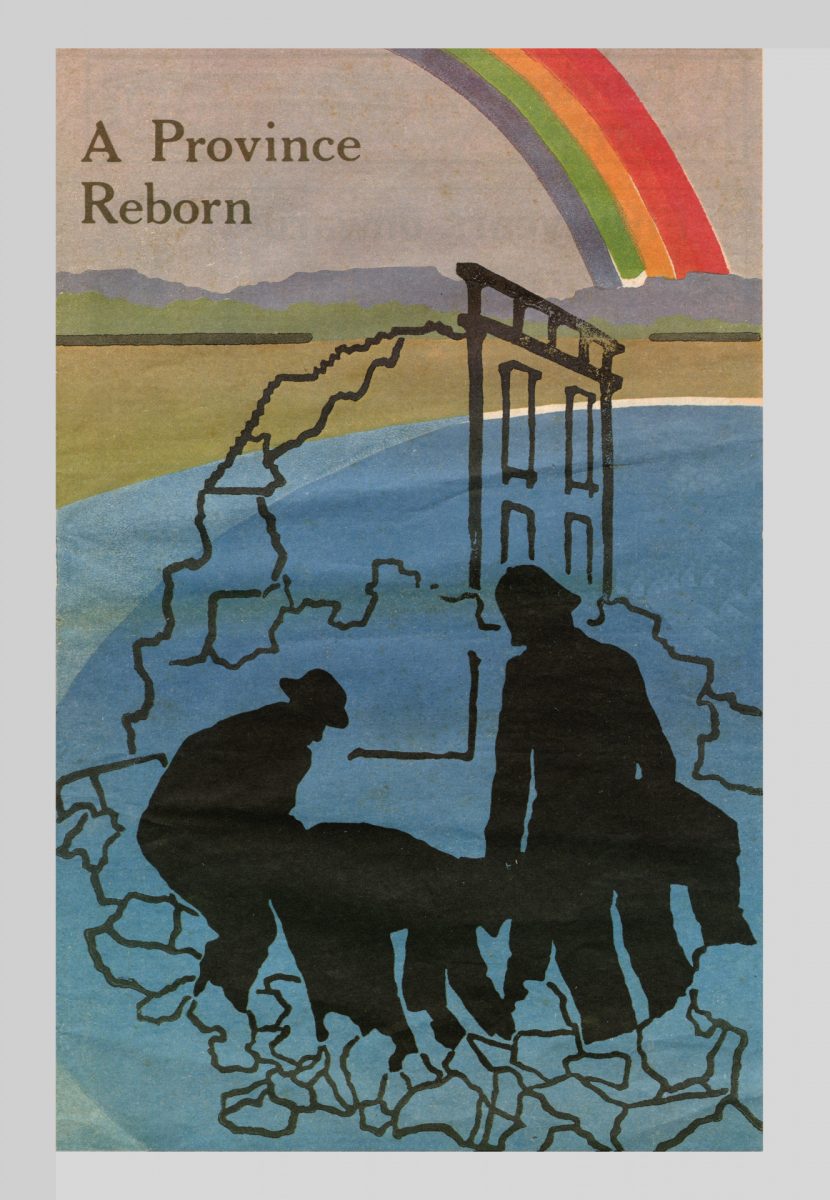

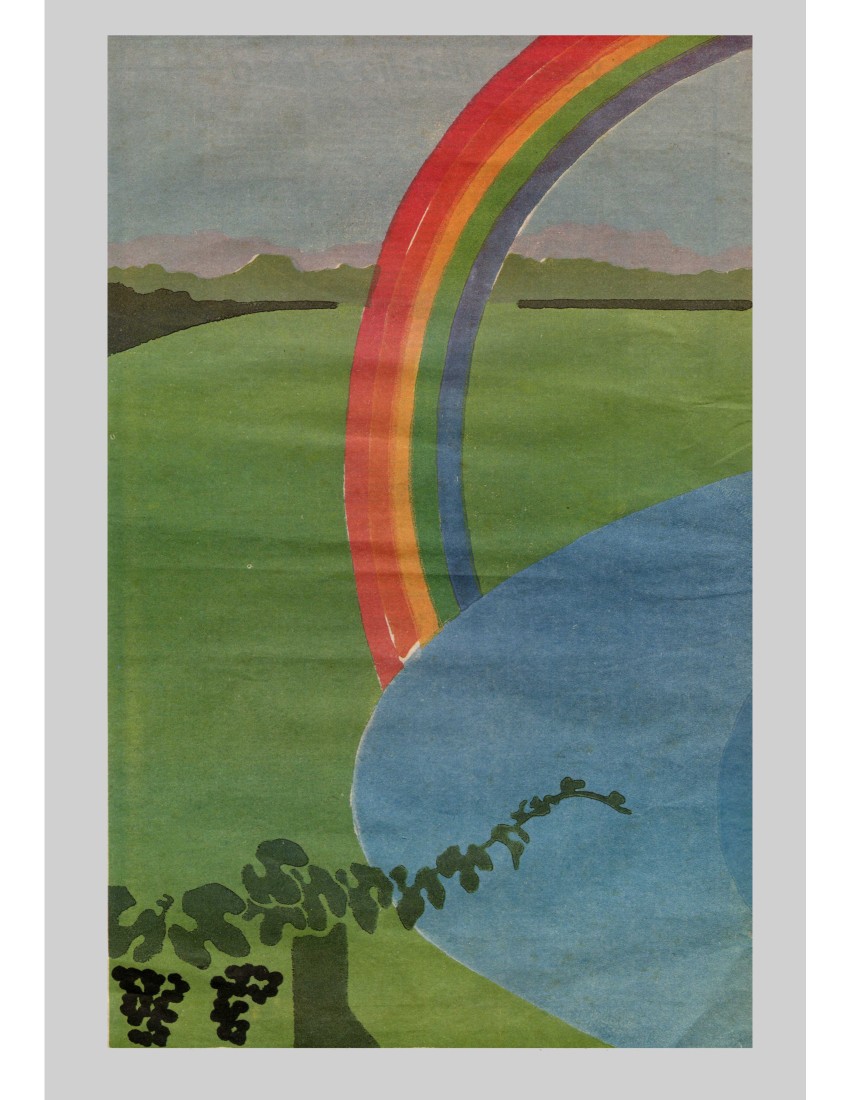

DESIGN AWARD

Mrs Janet Campbell, a 43-year-old self-taught Napier artist and mother of five, designed and created the cover of this commemorative issue.

She spent two months on the project to win the $500 design prize offered by The Daily Telegraph.

Mrs Campbell used lino prints, with three plates, each with six colours, for her finished work.

Her front panel was designed to depict gloom and destruction against a background of the sweep of Hawke Bay and the “clear Hawke’s Bay skies” which so impressed Mrs Campbell when she first came to the province from Wellington some 30 years ago.

The back panel uses grapes to represent growth and prosperity. The two sections are linked by a rainbow to symbolise hope.

She has been painting actively for about 10 years and is an artist member of the Hawke’s Bay Art Gallery. This is her first success in an art competition, although she exhibits regularly in the gallery’s annual exhibitions.

The original will hang in the main foyer of the Daily Telegraph in Napier.

A Province Reborn Page 3

WHAT HIT HAWKE’S BAY?

GEORGE EIBY, recently retired superintendent of the Seismological Observatory of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Wellington, looks at the lessons of the 1931 earthquake in the light of a further fifty years’ research.

Earthquakes are as inescapable as the weather. Even Mars and the Moon have them. Here on earth, seismologists report that every year there are a couple of million of them strong enough to be felt, a thousand or so that could bring down chimneys, and a dozen potential disasters. It’s just as well that so much of our earth is ocean, mountain, desert, or uninhabited forest that our chances of being hit by a big one are small enough.

How is it then that we keep reading of distant disasters that kill a hundred times more people than all New Zealand shocks taken together? The answer is not bigger earthquakes, but worse buildings!

One of the earliest lessons from the Hawke’s Bay earthquake was the need for strict building laws, and out engineers have come to be among the leaders in the art of designing earthquake-resisting structures.

There has also been astonishing progress in understanding how and why earthquakes happen. Some seismologists are raising hopes that reliable earthquake forecasting is not far away. Others insist that forecasting is a side issue; that there is little point in predicting when cities will fall down, and that we should concentrate upon making them stand up. Both schools of thought agree that we need a sound knowledge of the habits of earthquakes.

Piecing the earthquake story together has been a long business, and we have yet to reach the end of it. As long ago as the eighteenth century John Michell realised that waves travelling through the solid Earth were responsible for shaking down buildings, and suggested ways of tracing them back to their source. By about 1900 recording instruments had been invented, and we had learned a great deal more about the kinds of waves involved, and how they travelled.

We also knew that the shocks were a consequence of the processes that built mountains, and shaped the face of the Earth. Rocks far underground were fractured and set off the seismic waves. If the shock was big enough and shallow enough, a great crack could break through to the surface and appear as what geologists call a fault.

After the big San Francisco earthquake in 1906, H. F. Reid examined the displacements of the ground near the San Andreas Fault, and realised that what had happened was an “elastic rebound”. A long slow accumulation of strain had finally brought the rocks to break-point, and released the stored energy. The earthquake was not something sudden and abnormal, but a return to normal from a condition of strain.

That the strains are going on is clear enough from the folds and fractures that can be seen in rocks almost anywhere, but where do they come from? During the last few years, earth scientists have arrived at an explanation they call “plate tectonics”.

As with most important scientific theories, the basic ideas of plate tectonics are simple, but they turn out to explain most features of the Earth’s surface, from the broad pattern of continents and oceans to earthquakes, volcanoes and the deep trenches in the ocean floors.

Great fractures have been found to divide the outermost layers of the Earth into about seven large rigid plates which float on the more plastic material of the mantle underneath. The Earth’s internal heat keeps this material in slow circulation. It rises beneath the great central mountain ranges that cross the ocean floors, and moves outwards towards the margins of the continents as it cools. There it descends into the mantle once more, and is melted and re-absorbed.

The plates are carried along by this movement, which brings their edges into collision, folding and fracturing them, and producing belts of earthquakes and volcanoes. Because they are rigid, the central parts of the plates are comparatively stable.

New Zealand lies at the meeting of two plates. To the west, the Indian plate carries both Australia and India, while to the east the Pacific Plate forms the floor of the ocean, and is being driven beneath the North Island. This thrusting accounts for the Hawke’s Bay earthquake of 1931 and, indeed, for all the earthquakes in the North Island and the northern half of the South Island.

In Fiordland, the same forces are responsible, but here it is the Pacific plate that is on top, and the Indian Plate that is being driven beneath it. The complexities of the transition are a subject of lively scientific argument.

Since European settlement began, New Zealand has had about fifteen earthquakes within half a magnitude or so of the size of the Hawke’s Bay one, yet only the Murchison shock in 1929 produced casualties running to double figures, and none has caused comparable damage to property. Why was it so destructive?

The short answer is that its origin was unusually close to centres of population, and close to the surface. In places where a plate is being thrust back into the mantle, very deep shocks are often found. New Zealand’s deepest – under north Taranaki – were more than 600km down; but the great majority of shocks, including all the destructive ones, originate within the crust, about 30km thick.

In 1931, there were few good seismographs in New Zealand, and we had to get most of our information about the Hawke’s Bay earthquake from overseas recordings, so it would be rash to be too dogmatic about the position of the origin.

The best estimates put the epicentre (the point on the surface directly over the origin) between Rissington and Patoka, about 25km north-west of Napier, but this could be as much as 20km out in any direction. The depth was no more than 15 or 20km.

The magnitude of the shock was 7.9, about the same as that of the Murchison earthquake two years earlier. It is not the country’s biggest shock, that distinction going to the south-west Wairarapa earthquake of 1855, which had a magnitude of at least 8. The Inangahua earthquake in 1968, the last of New Zealand’s really serious shocks, reached only 7.1.

There is more to a big earthquake than an underground breaking of rocks and the radiation of a train of waves. The whole of the Earth’s crust must readjust, with consequent uplifts and subsidences, and a sequence of aftershocks that may persist for a year or more. In Hawke’s Bay two common accompaniments of a large shock were missing – a tsunami (or seismic sea-wave) and visible displacements along a geological fault. Some minor breakages occurred near Paki Paki, but they are not considered to be part of the main causative fracture.

The curious disruption of the tides and the draining of the Ahuriri Lagoon were not the result of a tsunami, but of the regional uplift that was a permanent result of the earthquake. An area some 90km long and 15km wide was raised by a maximum of about 3 metres. There was also settlement of poorly compacted land near the mouth of the Tutaekuri River and on the Heretaunga Plains, with the expulsion of sand and mud, and permanent changes to the drainage pattern.

The story of the casualties and the damaged buildings is not part of the seismologists brief, but he must answer one final question: Could it happen again? So far as the geological story is concerned, the answer is yes, the movement of the plates is not going to stop.

Hawke’s Bay will have more earthquakes, and a few of them will be as big or bigger than the one in 1931. What need not be repeated is the loss of life and property. We know how we should build, and where we should build to withstand even the strongest likely shocks. Are we wise enough to apply our knowledge? That is another matter.

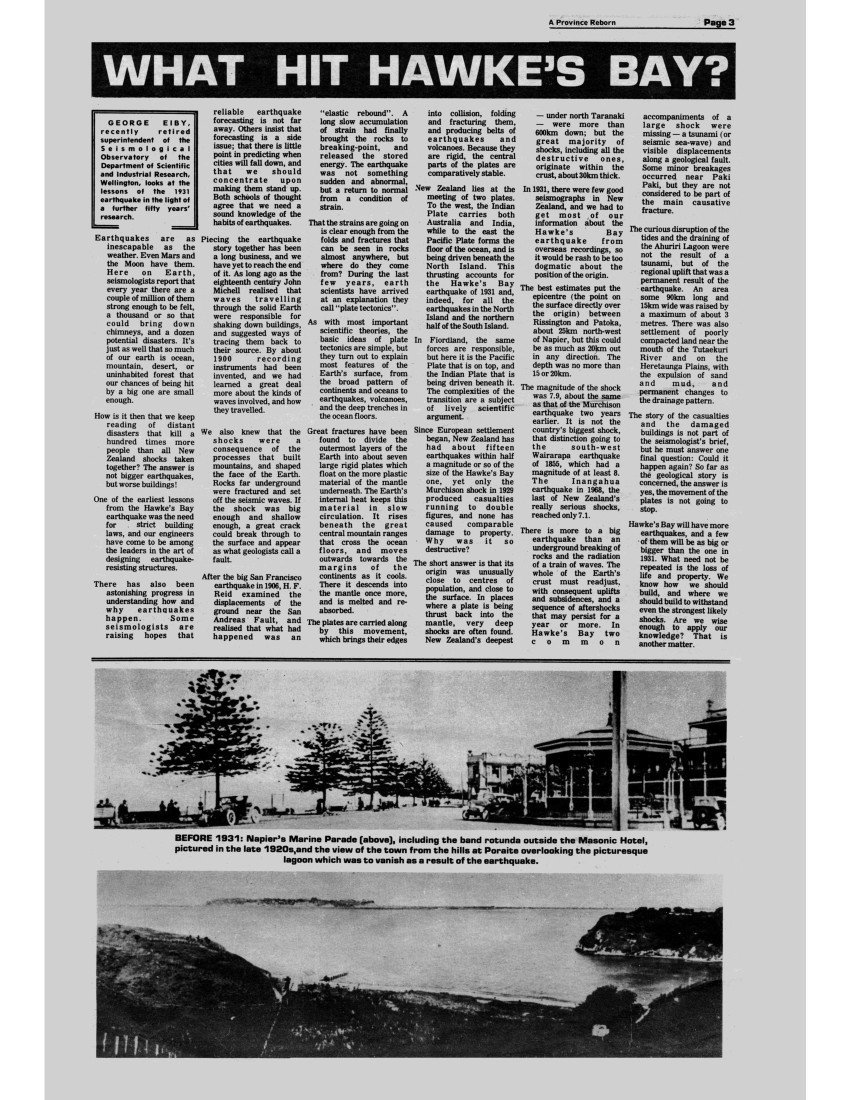

BEFORE 1931: Napier’s Marine Parade (above), including the band rotunda outside the Masonic Hotel, pictured in the late 1920s, and the view of the town from the hills at Poraite [Poraiti] overlooking the picturesque lagoon which was to vanish as a result of the earthquake.

A Province Reborn Page 5

Tuesday, February 3, 1931

“A week ago we were very proud of our little town. In fact, we knew of no more desirable place of residence on the face of the earth. Today it is known as the ‘stricken area’ and WE are the ‘refugees’. If you could see the conditions under which we live, you would not be altogether surprised at not hearing from us sooner.

“Last Tuesday, at 11, I was interviewing a client in my room at Hastings when, without warning, a violent shake occurred, followed immediately by a tossing about more than anything you can conceive.

“For about a minute I was hanging on like grim death to my table, wondering if I could continue to hold on. If I had let go, I would have banged immediately on the floor. The client fell immediately and kept telling me he was in the safest place, under the table, and I skated across the room to him.

“There was a tremendous row outside of falling buildings and, by the time I reached the street, I was looking on an entirely new scene. Solid brick buildings had gone down flat like castles of cards. Roofs were hanging sideways, great heaps of bricks were everywhere, and the air was full of dust. Every minute or two another wild rattle would set us watching for overhead wires or more falling masonry.

“The worse scene was people, hurrying about with bleeding heads or bound-up wounds – grey, black, red or white, according to the material they had been near. A few minutes later it was ‘Poor old Colebourne’s dead’ (manager of Williams and Kettle), or ‘So and so’s leg’s broken’ or ‘There are three dead just outside Roach’s and goodness knows how many inside’.

“Next, all our Napier folk wanted to get in to see how their people had fared and I started off with nine in the car – married men and girl typists. The latter were plucky, but were naturally weeping spasmodically.

“The first bridge showed that it was not going to be plain sailing. The approaches were gone and we detoured to another route.

“On we went, sometimes mounting one-foot steps and dropping down others and leaving the road altogether on account of fissures. Hundreds of cars were travelling both ways, all full of anxious people. Others were stuck in the road with one wheel in a hole.

“When we reached the town (of Napier), several big fires were blazing and to get home I had to make a detour along the hills. It was (there goes another shake) an immense relief to see Alison at the gate and…

“The next two days were a nightmare. We learnt that our neighbours and K’s great friend [Kathleen, his wife], old Mrs McLean, was in the Cathedral, which had collapsed like a pack of cards at the first shake. Others were anxiously awaiting the return of sons and daughters, fathers and mothers.

“To our relief, Mrs McLean was brought up in a car, greatly shaken, but not much the worse. No one, however, had heard of her daughter Dorothy, who had left her to go shopping.

“Night came on and we had rows of mattresses pulled out on our side path or drive, as we call it. Twenty-one spent the first night there – two also were mothers with daughters missing.

“As soon as all were bedded somewhere, the search for the missing commenced, but by that time the fire had swept the whole business area of Napier and rescue work was out of the question, except in outlying parts. Not a single building in Napier or Hastings could be occupied and all lights and water were cut off by broken pipes, but the work went on all night.

“The biggest field hospital was at Napier racecourse (four miles out) and roads were frightful with bumps, hollows and open fissures.

“I peered into dozens and dozens of patient’s faces, trying to find Dorothy McLean, but it was all in vain. The poor girl’s body was only identified by her brother (who is with me now) today. The other missing girl was found three days ago.

“Another half-day and evening I was helping a husband to find his wife, who was reported again and again to be alive with a broken leg. That, too turned out to be fruitless. Her body has since been found. I could only take her little girl home with a broken arm.

“It is impossible to describe the conditions under which everyone was working – no light, no telephones, no houses, no sanitary conveniences, only carted water, nobody to give information, no names attached to the patients, half the roads blocked. The only redeeming feature then and since has been no rain.

“I omitted to say no shops to buy or commandeer anything. (Another good shake). (And another). Alan quietly remarked: ‘That’s the first for a long time’.

“Napier now looks like the last days of Pompeii. What the earthquake spared the fire took. That applies only to the business area.

“Most of the houses are like mine – or a little worse – the chimneys down and a few big gaps in the roof, the drawing room full of bricks, pictures, mirrors, vases in splinters everywhere. The pantry is a huge sticky “fruit salad”, every room with its chairs and furniture upside down, bricks and brick dust inside and out, wherever you look, and you never wish to see a brick again.

“I estimate my repair bill at 200 pounds but, allowing for a hundred or two houses and, in many cases, sections too that will have to be abandoned, I put down the average at 300 pounds per house, including furniture. Multiply that by 5000 houses and you have 1.5 million pounds for residences alone. Add to that the business premises and Hastings and the country, and you will reach seven or eight million.

“The loss of life will be about 300 in all. Bodies are still being found every day. In some respects things are being exaggerated, but nearly every visitor finds things ever so much worse than they expected. I could not have conceived the scene if I had not experienced it.

“Our life is a strange one, 75 per cent of the citizens are out of the town, including practically all the children and nine-tenths of the women. Those left are all living in tents and motor-sheds.

“We are all on a common level. All those left behind know everybody else. Everyone helps everyone. Anyone going into town asks for letters and telegrams for all his neighbours. Little groups of tents have arisen in all flat sections on the hills.

“The neighbouring towns have been grand – Wellington, Palmerston North, Dannevirke, Feilding . . . “(All that survives of the letter, the last page/pages having been lost.)

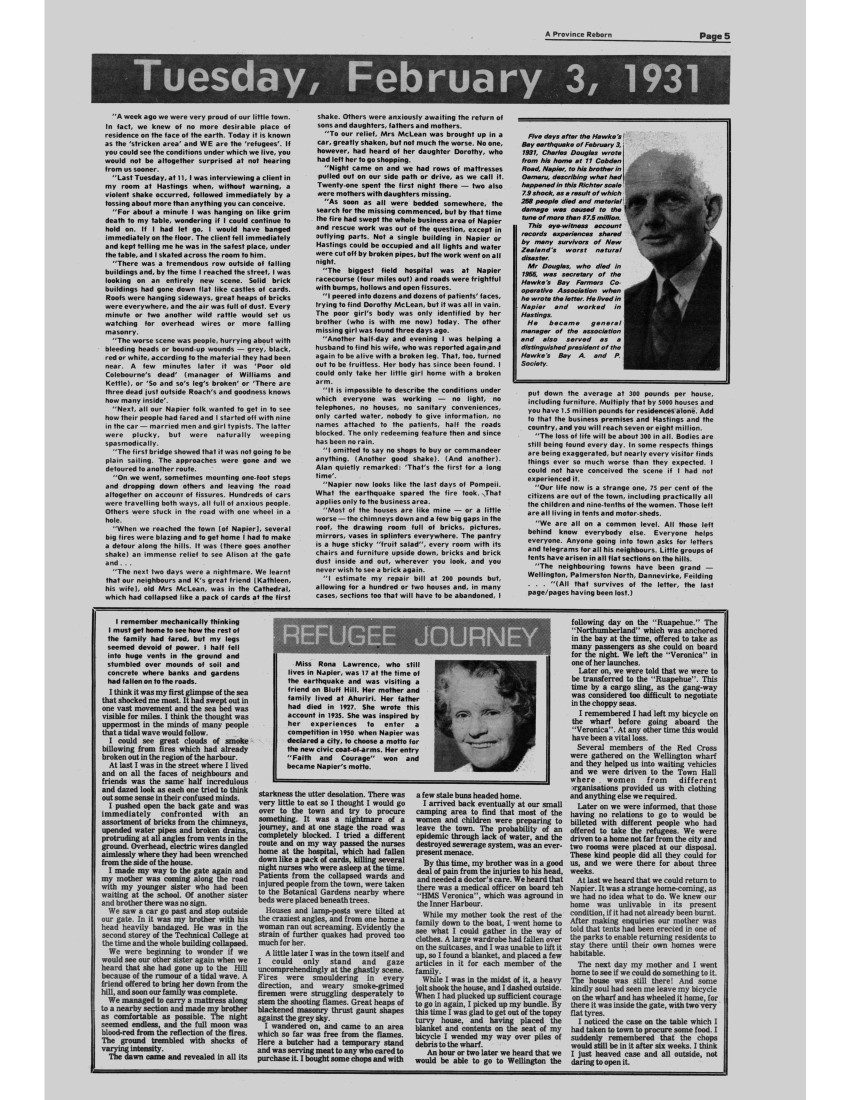

Five days after the Hawke’s Bay earthquake of February 3, 1931, Charles Douglas wrote from his home at 11 Cobden Road, Napier, to his brother in Oamaru, describing what had happened in this Richter scale 7.9 shock, as a result of which 258 people died and material damage was caused to the tune of more than $7.5 million.

This eye-witness account records experiences shared by many survivors of New Zealand’s worst natural disaster.

Mr Douglas, who died in 1955, was secretary of the Hawke’s Bay Farmers Co-operative Association when he wrote the letter. He lived in Napier and worked in Hastings.

He became general manager of the association and also served as a distinguished president of the Hawke’s Bay A. and P. Society.

REFUGEE JOURNEY

Miss Rona Lawrence, who still lives in Napier, was 17 at the time of the earthquake and was visiting a friend on Bluff Hill. Her mother and father lived at Ahuriri. Her father had died in 1927. She wrote this account in 1935. She was inspired by her experiences to enter a competition in 1950 when Napier was declared a city, to choose a motto for the new civic coat-of-arms. Her entry “Faith and Courage” won and became Napier’s motto.

I remember mechanically thinking I must get home to see how the rest of the family fared, but my legs seemed devoid of power. I half fell into huge vents in the ground and stumbled over mounds of soil and concrete where banks and gardens had fallen on to the roads.

I think it was my first glimpse of the sea that shocked me the most. It had swept out in one vast movement and the sea bed was visible for miles. I think the thought was uppermost in the minds of many people that a tidal wave would follow.

I could see great clouds of smoke billowing from fires which had already broken out in the region of the harbour.

At last I was in the street where I lived and on all the faces of neighbours and friends was the same half incredulous and dazed look as each one tried to think out some sense in their confused minds.

I pushed open the back gate and was immediately confronted with an assortment of bricks from the chimneys, upended water pipes and broken drains, protruding at all angles from vents in the ground. Overhead, electric wires dangled aimlessly where they had been wrenched from the side of the house.

I made my way to the gate again and my mother was coming along the road with my younger sister who had been waiting at the school. Of another sister and brother there was no sign.

We saw a car go past and stop outside our gate. In it was my brother with his head heavily bandaged. He was in the second storey of the Technical College at the time and the whole building collapsed.

We were beginning to wonder if we would see our other sister again when we heard that she had gone up to the Hill because of the rumour of a tidal wave. A friend offered to bring her down from the hill, and soon our family was complete.

We managed to carry a mattress along to a nearby section and made my brother as comfortable as possible. The night seemed endless, and the full moon was blood-red from the reflection of the fires. The ground trembled with shocks of varying intensity.

The dawn came and revealed in all its starkness the utter desolation. There was very little to eat so I thought I would go over to the town and try to procure something. It was a nightmare of a journey, and at one stage the road was completely blocked. I tried a different route and on my way passed the nurses home at the hospital, which had fallen down like a pack of cards, killing several night nurses who were asleep at the time. Patients from the collapsed wards and injured people from the town, were taken to the Botanical Gardens nearby where beds were placed beneath trees.

Houses and lamp-posts were tilted at the craziest angles, and from one home a woman ran out screaming. Evidently the strain of further quakes had proved too much for her.

A little later I was standing in the town itself and I could only stand and gaze at the ghastly scene. Fires were smouldering in every direction, and weary smoke-grimed firemen were struggling desperately to stem the shooting flames. Great heaps of blackened masonry thrust gaunt shapes against the grey sky.

I wandered on, and came to an area which so far was free from the flames. Here a butcher had a temporary stand and was serving meat to any who cared to purchase it. I bought some chops and with few stale buns headed home.

I arrived back eventually at our small camping area to find that most of the women and children were preparing to leave the town. The probability of an epidemic through lack of water, and with the destroyed sewerage system, was an ever-present menace.

By this time, my brother was in a good deal of pain from the injuries to his head, and needed a doctor’s care. We heard that there was a medical officer on board the (sic) “HMS Veronica”, which was aground in the Inner Harbour.

While my mother took the rest of the family down to the boat, I went home to see what I could gather in the way of clothes. A large wardrobe had fallen over on the suitcases, and I was unable to lift it up, so I found a blanket, and placed a few articles in it for each member of the family.

While I was in the midst of it, a heavy jolt shook the house, and I dashed outside. When I had plucked up sufficient courage to go in again, I picked up my bundle. By this time I was glad to get out of the topsy turvy house, and having placed the blanket and contents on the seat of my bicycle I wended my way over piles of debris to the wharf.

An hour or two later we heard that we would be able to go to Wellington the following day on the “Ruapehue.” The “Northumberland” which was anchored in the bay at the time, offered to take as many passengers as she could on board for the night. We left the “Veronica” in one of her launches.

Later on, we were told that we were to be transferred to the “Ruapehue”. This time by a cargo sling, as the gang-way was considered too difficult to negotiate in the choppy seas.

I remembered I had left my bicycle on the wharf before going aboard the “Veronica”. At any other time this would have been a vital loss.

Several members of the Red Cross were gathered on the Wellington wharf and they helped us into waiting vehicles and we were driven to the Town Hall where women from different organisations provided us with clothing and anything else we required.

Later on we were informed, that those having no relations to go to would be billeted with different people who had offered to take the refugees. We were driven to a home not far from the city and two rooms were placed at our disposal. These kind people did all they could for us, and we were there for about three weeks.

At last we heard that we could return to Napier. It was a strange home-coming, as we had no idea what to do. We knew our home was unlivable in its present condition, if it had not already been burnt. After making enquiries our mother was told that tents had been erected in one of the parks to enable returning residents to stay there until their own homes were habitable.

The next day my mother and I went home to see if we could do something to it. The house was still there! And some kindly soul had seen me leave my bicycle on the wharf and has wheeled it home, for there it was inside the gate, with two very flat tyres.

I noticed the case on the table which I had taken to town to procure some food. I suddenly remembered that the chops would still be in it after six weeks. I think I just heaved case and all outside, not daring to open it.

Page 6 A Province Reborn

They saw it happen

Stories of individual experiences of February 3, 1931, as told to the chief reporter of The Daily Telegraph, Brian McErlane.

“End of the world”

The actions of Claude Temperton, chief clerk of the New Zealand Insurance office in Napier 50 years ago, saved the lives of several people.

Mr Tom Prebble, who was a 19-year-old clerk working in the NZI building, then on the corner of Tennyson and Hastings Streets, recalls the events:

“Mr Temperton, whose son Bruce also worked for the NZI, stopped people rushing out of the building when it was still shaking following the first big earthquake.

“If he hadn’t done this, I am certain several of our staff would have been killed. As it was, one of the girls (a Miss Brandon) who worked upstairs in the solicitor’s office, was killed when a piece of masonry fell on her.”

Mr Prebble, who worked for the NZI for 41 years, retired as manager in Napier in 1971.

“I was just sitting at my desk in the office, which was opposite the Masonic Hotel, when I felt a terrible rumble,” he said.

“I said then: ‘That’s a big truck going up the street.’ Then she blew. It was just whoof, whoof. Very few could stand. I had a pole next to me so I grabbed that and I was later told that I said: ‘This is the end of the world.’

“I was also told that I grabbed one of the office girl’s legs and hung on, but I can’t remember that.

“The building was made of large Oamaru stone blocks lined with wood and a wooden floor, but they had limestone filler between the first and second floors to deaden the sound.

“The result was that you could hardly see a thing for dust and rubble. Bricks also flew off the parapets of the Masonic Hotel and were hurled across the road through our windows.”

Mr Prebble was one of nine people in the office, including his sister, Maisie (no Mrs Ogilvie), and when they left together they walked along Herschell Street.

“We saw a girl lying dead outside the Hawke’s Bay County Council building,” he said. “We then came back along the Marine Parade which was undulating just like a sea.

“The whole front of the Masonic Hotel had fallen out. We saw an amazing rescue. A man was sitting on his bed on the top floor Apparently caught by a beam. The fire brigade put up a ladder to rescue him.

The fireman would run up the ladder, but would then run down again as the building was shaking terribly. He did that several times before he eventually freed the man and they both ran down the ladder, one after the other.

“After this our attention was drawn to the sea. It had receded such a long way and this was why there was a fear of a tidal wave coming and people were told to go up the hill.”

As it was Mr Prebble was one of several men who were detailed to go to the hospital and help. “We got a lift up in a car and when we got there the hospital was a terrible mess,” he said.

Mr Prebble said he and others assisted by carrying blankets to the first-aid post at the top of the Botanical Gardens. He also remembers seeing rescuers recovering a girl from the bottom of the demolished nurses’ home.

“She had been on night duty and had been trapped. She spent more than four hours there before they got her out.”

Mr Prebble said the nurse was Miss Tuppy Loten, whose father was the headmaster of Te Aute College. She is now Mrs Sam Dwyer, the mother of Social Credit Party deputy leader, Jeremy Dwyer.

Mr Prebble said about 35 people slept on the lawn outside his parents’ home for several days, while 10 days after the earthquake he and the other NZI staff were sent to Dannevirke where they worked in the company’s office for six months.

“Just when we were leaving home there was another quake which was just as big as the first one,” he said, “Our house really shook.

“We eventually got on the train that had come up from Wellington with many men seeking work in the rebuilding of the town as this was in the midst of the Depression. However, many of these men never got off the train. That shake was enough for them and they went straight back to Wellington again.”

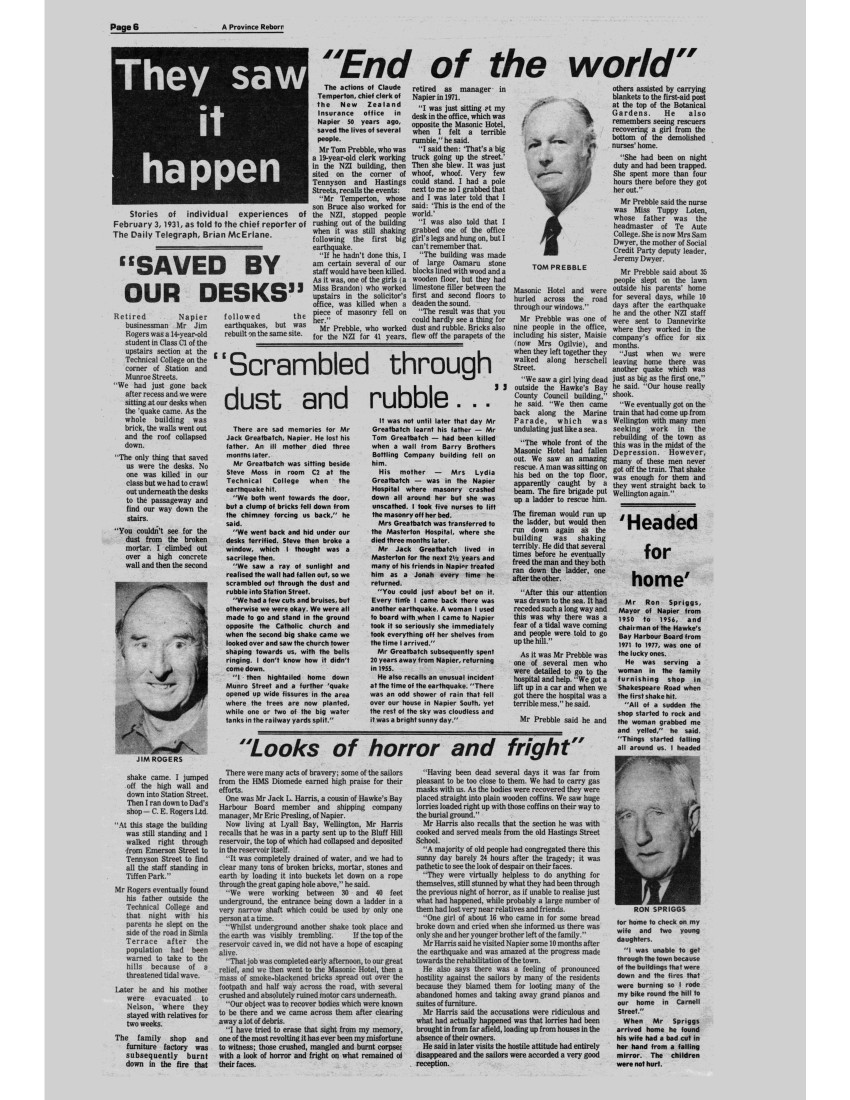

Photo caption – TOM PREBBLE

“SAVED BY OUR DESKS”

Retired Napier businessman Mr Jim Rogers was a 14-year-old student in Class C1 of the upstairs section at the Technical College on the corner of Station and Munroe Streets.

“We had just gone back after recess and we were sitting at our desks when the ‘quake came. As the whole building was brick, the walls went out and the roof collapsed down.

“The only thing that saved us were the desks. No one was killed in our class but we had to crawl out underneath the desks to the passageway and find our way down the stairs.

“You couldn’t see for the dust from the broken mortar. I climbed out over a high concrete wall and then the second shake came. I jumped off the high wall and down into Station Street. Then I ran down to Dad’s shop – C. E. Rogers Ltd.

“At this stage the building was still standing and I walked right through from Emerson Street to Tennyson Street to find all the staff standing in Tiffen Park.”

Mr Rogers eventually found his father outside the Technical College and that night with his parents he slept on the side of the road in Simla Terrace after the population had been warned to take to the hills because of the threatened tidal wave.

Later he and his mother were evacuated to Nelson, where they stayed with relatives for two weeks.

The family shop and furniture factory was subsequently burnt down in the fire that followed the earthquakes, but was rebuilt on the same site.

Photo caption – JIM ROGERS

“Scrambled through dust and rubble…”

There are sad memories for Mr Jack Greatbatch, Napier. He lost his father. An ill mother died three months later.

Mr Greatbatch was sitting beside Steve Moss in room C2 at the Technical College when the earthquake hit.

“We both went towards the door, but a clump of bricks fell down from the chimney forcing us back,” he said.

“We went back and hid under our desks terrified. Steve then broke a window, which I thought was a sacrilege then.

“We saw a ray of sunlight and realised the wall had fallen out, so we scrambled out through the dust and rubble into Station Street.

“We had a few cuts and bruises, but otherwise we were okay. We were all made to go and stand in the ground opposite the Catholic church and when the second big shake came we looked over and saw the church tower shaping towards us, with the bells ringing. I don’t know how it didn’t come down.

“I then hightailed home down Munro Street and a further ‘quake opened up wide fissures in the area where the trees are now planted, while one or two of the big water tanks in the railway yards split.”

It was not until later that day Mr Greatbatch learnt his father – Mr Tom Greatbatch – had been killed when a wall from Barry Brothers Bottling Company building fell on him.

His mother – Mrs Lydia Greatbatch – was in the Napier Hospital where masonry crashed down all around her but she was unscathed. I[It] took five nurses to lift the masonry off her bed.

Mrs Greatbatch was transferred to the Masterton Hospital, where she died three months later.

Mr Jack Greatbatch lived in Masterton for the next 2 1/2 years and many of his friends in Napier treated him as a Jonah every time he returned.

“You could just about bet on it. Every time I came back there was another earthquake. A woman I used to board with when I came to Napier took it so seriously she immediately took everything off her shelves from the time I arrived.”

Mr Greatbatch subsequently spent 20 years away from Napier, returning in 1955.

He also recalls an unusual incident at the time of the earthquake. “There was an odd shower of rain that fell over our house in Napier South, yet the rest of the sky was cloudless and it was a bright sunny day.”

‘Headed for home’

Mr Ron Spriggs, Mayor of Napier from 1950 to 1956, and chairman on the Hawke’s Bay Harbour Board from 1971 to 1977, was one of the lucky ones.

He was serving a woman in the family furnishing shop in Shakespeare Road when the first shake hit.

“All of a sudden the shop started to rock and the woman grabbed me and yelled,” he said. Things started falling all around us. I headed for home to check on my wife and two young daughters.

“I was unable to get through the town because of the buildings that were down and the fires that were burning so I rode my bike around the hill to our home in Carnell Street.”

When Mr Spriggs arrived home he found his wife had a bad cut in her hand from a falling mirror. The children were not hurt.

Photo caption – RON SPRIGGS

“Looks of horror and fright”

There were many acts of bravery; some of the sailors from the HMS Diomedes earned high praise for their efforts.

One was Mr Jack L. Harris, a cousin of Hake’s Bay Harbour Board member and shipping company manager, Mr Eric Presling, of Napier.

Now living at Lyall Bay, Wellington, Mr Harris recalls that he was in a party sent up to the Bluff Hill reservoir, the top of which had collapsed and deposited in the reservoir itself.

“It was completely drained of water, and we had to clear many tons of broken bricks, mortar, stones and earth by loading it into buckets let down on a rope through the great gaping hole above,” he said.

“We were working between 30 and 40 feet underground, the entrance being down a ladder in a very narrow shaft which could be used by only one person at a time.

“Whilst underground another shake took place and the earth was visibly trembling. If the top of the reservoir caved in, we did not have a hope of escaping alive.

“That job was completed early afternoon, to our great relief, and we then went to the Masonic Hotel, then a mass of smoke-blackened bricks spread out over the footpath and half way across the road, with several crushed and absolutely ruined motor cars underneath.

“Our object was to recover bodies which were known to be there and we came across them after clearing away a lot of debris.

“I have tried to erase that sight from my memory, one of the most revolting it has ever been my misfortune to witness; those crushed, mangled and burnt corpses with a look of horror and fright on what remained of their faces.

“Having been dead several days it was far from pleasant to be too close to them. We had to carry gas masks with us. As the bodies were recovered they were placed straight into plain wooden coffins. We saw huge lorries loaded right up with those coffins on their way to the burial ground.”

Mr Harris also recalls that the section he was with cooked and served meals from the old Hastings Street School.

“A majority of old people had congregated there this sunny day barely 24 hours after the tragedy; it was pathetic to see the look of despair on their faces.

“They were virtually helpless to do anything for themselves, still stunned by what they had been through the previous night of horror, as if unable to realise just what had happened, while probably a large number of them had lost very near relatives and friends.

“One girl of about 16 who came in for some bread broke down and cried when she informed us there only she and her younger brother left of the family.”

Mr Harris said he visited Napier some 10 months after the earthquake and was amazed at the progress made towards the rehabilitation of the town.

He also says there was a feeling of hostility against the sailors by many of the residents because they blamed them for looting many of the abandoned homes and taking away grand pianos and suites of furniture.

Mr Harris said the accusations were ridiculous and what had actually happened was that lorries had been brought from far afield, loading up from houses in the absence of their owners.

He said in later visits the hostile attitude had entirely disappeared and the sailors were accorded a very good reception.

A Province Reborn Page 7

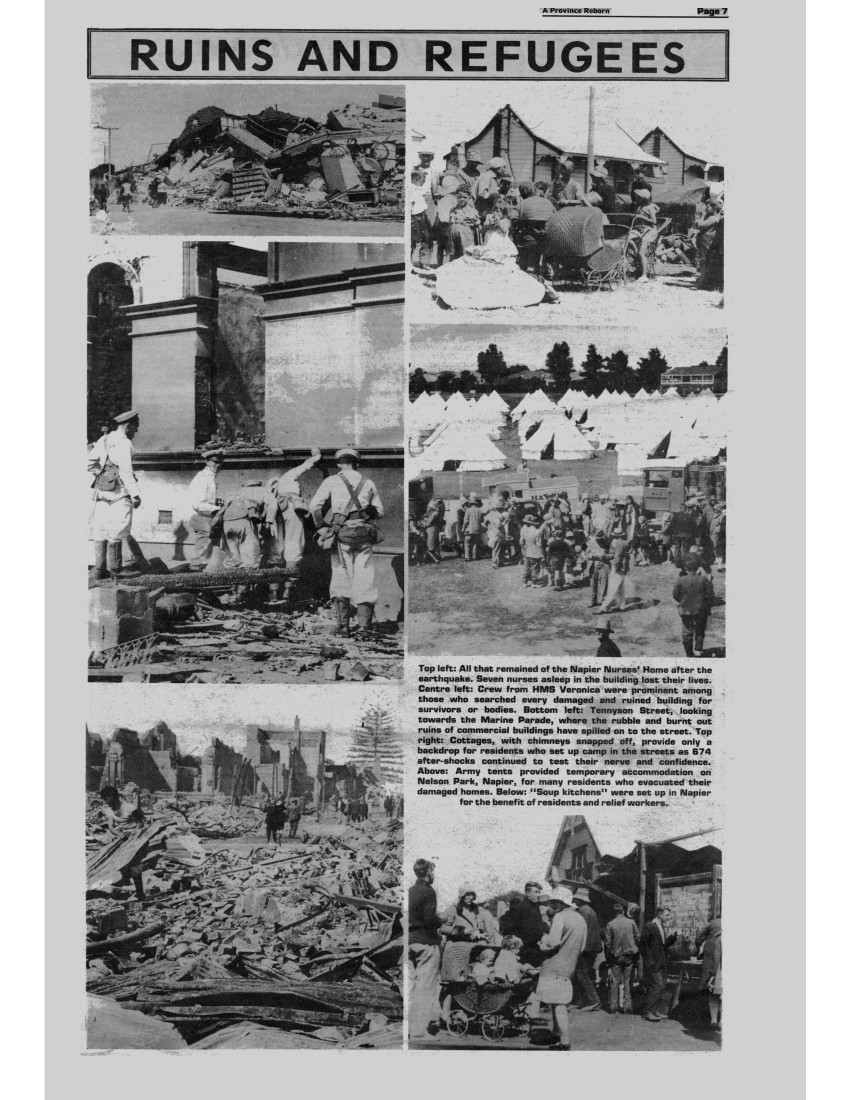

RUINS AND REFUGEES

Top left: All that remained of the Napier Nurses’ Home after the earthquake. Seven nurses asleep in the building lost their lives. Centre left: Crew from HMS Veronica were prominent among those who searched every damaged and ruined building for survivors or bodies. Bottom left: Tennyson Street, looking towards the Marine Parade, where the rubble and burnt out ruins of commercial buildings have spilled on to the street. Top right: Cottages, with chimneys snapped off, provide only a backdrop for residents who set up camp in the streets as 674 after-shocks continued to test their nerve and confidence. Above: Army tents provided temporary accommodation on Nelson Park, Napier, for many residents who evacuated their damaged homes. Below: “Soup kitchens” were set up in Napier for the benefit of residents and relief workers.

Page 8 A Province Reborn

“Their sun is gone down…

By staff reporter, John Cousins)

Falling masonry – creating a deafening roar and stirring up plumes of dust which rose to block out the sun – terrified, injured and killed as forces of nature unleashed themselves on February 3, 1931.

Two hundred and fifty-eight people lost their lives in the minutes and hours that followed. Many more throughout the province were injured,

Those who emerged unscathed were stunned and shattered by the experience. In communities the size those days of Napier, Hastings, Wairoa, Waipawa and Waipukurau, few did not suffer the loss of family, relatives or friends.

The tumble of masonry which caused the first casualties is vividly remembered by Miss Nancy Hobson who was inside her father’s chemist shop under the old Masonic Hotel.

“I felt it coming. My first instinct was to run outside. I had barely got onto the road when the whole face of the hotel fell.

“It was like being on the deck of a ship in very rough seas. You didn’t know where your feet were going to hit the ground.

“I tripped on wires and fell over people. I couldn’t control my walking at all. It was very dark and there was this extraordinary roar of falling masonry that went on for a very long time,” she recalls today.

These were the conditions which killed so many people fleeing to escape buildings that rocked violently.

Facades, cornices and parapets – popular architectural decorations of the time – toppled and struck death blows.

Several days later a journalist witnessed workmen removing a mound of rubble from what had been the entrance to the Masonic Hotel. He told readers that seven bodies were found “huddled together where they had tried to rush from the building”.

“Plumes of dust blocked the sun”

An even more horrific fate awaited the many who never made it to the streets.

Maimed, pinned down, or simply trapped inside buildings, they were at the mercy of fires which broke out in several chemist shops around town and which soon engulfed the whole main business centre of Napier.

Desperate attempts to save them were doomed by the heat of the fire or the weight of the rubble.

Firemen, sailors, policemen and civilians heard the screams of people perishing in the flames.

It was to be New Zealand’s worst natural disaster. Napier bore the brunt and 162 people perished in the town. In Hastings, 93 lost their lives and a further three people died at Wairoa.

The search for survivors began immediately. Townspeople were joined by crew from the HMS Veronica berthed at the port.

Fire fighting became almost impossible, mainly through a lack of water resulting from broken water mains.

Residents left their homes. Many camped on the beachfront; others gathered together on front lawns and other open spaces as the earthquakes continued.

Open areas such as the racecourse at Greenmeadows became a field hospital; Nelson Park was designated a refugee centre. As Napier and Hastings started to organise relief work, offers of assistance poured in from the whole of New Zealand.

The naval vessels HMS Dunedin and Diomedes dashed with relief equipment and workers from Auckland. Within hours virtually, medical and relief work was proceeding at pace with volunteer agencies such as Red Cross at the centre of activity.

Several of Miss Hobson’s friends were nurses sleeping off their night’s labours in the wards of the Napier Hospital. Eight were killed when the earthquake wrecked the nurses’ home.

Miss Amy Railey, pulled from the street-front rubble of The Daily Telegraph, remembers the tragedy which befell young police constable Tripney.

His wife, Annie, and their six-week-old son, David, were killed at the hospital. Alone, the constable dug their graves at Park Island – choosing against the mass grave for earthquake victims.

“Our little world was turned upside down with a vengeance,” she said.

For a long time afterwards, Miss Railey and her colleagues pondered the fate of a lady who worked upstairs in the Labour Department.

“We used to think she was quite old, but she probably wasn’t. Her name was Miss McHenry – that’s all I knew her as.

“We think she got caught coming back to the office. She was never heard of again. No trace was ever found of her,” she said.

“Our little world upside down”

Miss Connie Berry helped identify the bodies of two relatives who had gone to shop in Hastings. The two women were found among the rows of the dead lined up inside the temporary mortuary sited at the YMCA.

One of them was found among the 17 who died under the debris of Roachs department store.

Back in Napier that same afternoon, Miss Berry was commandeered to help a nurse treat the injured in Clive Square.

It was the anticipation of life which spurred the citizenry of both cities. They were inspired, too, by the gallantry of sailors from HMS Veronica.

Mrs Gladys Harris, enlisted by the Red Cross to carry out relief in Hastings, will never forget witnessing the grim task of searching through the ruins.

As a limb appeared the rescuers would group around and either cheer or lapse into a hushed silence, depending on whether the person was alive or dead.

In Napier the dead were taken to a temporary mortuary set up in the courthouse.

The list of injuries among the living reflected the rapidly rising death toll which was first hinted to the outside world 67 minutes after the ‘quake took place. A signaller on board HMS Veronica relayed the message: “Medical assistance required; fear considerable loss of life.”

The aged were hit hard; 15 perished in the Old People’s Home at Park Island.

Greenmeadows winemaker, Mr Tom McDonald, helped excavate the nine Catholic clergy or students who perished under the walls of the vestibule in the chapel of the Mount St Mary’s Seminary.

He was later appointed a “special constable” and had the unenviable task of picking up the remains of people found in the ruins. In this he worked alongside the pathologist.

Mr Desmond Duthie arrived in Napier from Wellington soon after the ‘quake to take charge of identification of the dead – a role he had been used to in wartime conditions.

Identification of badly charred bodies was sometimes carried out by no other clue than personal jewellery.

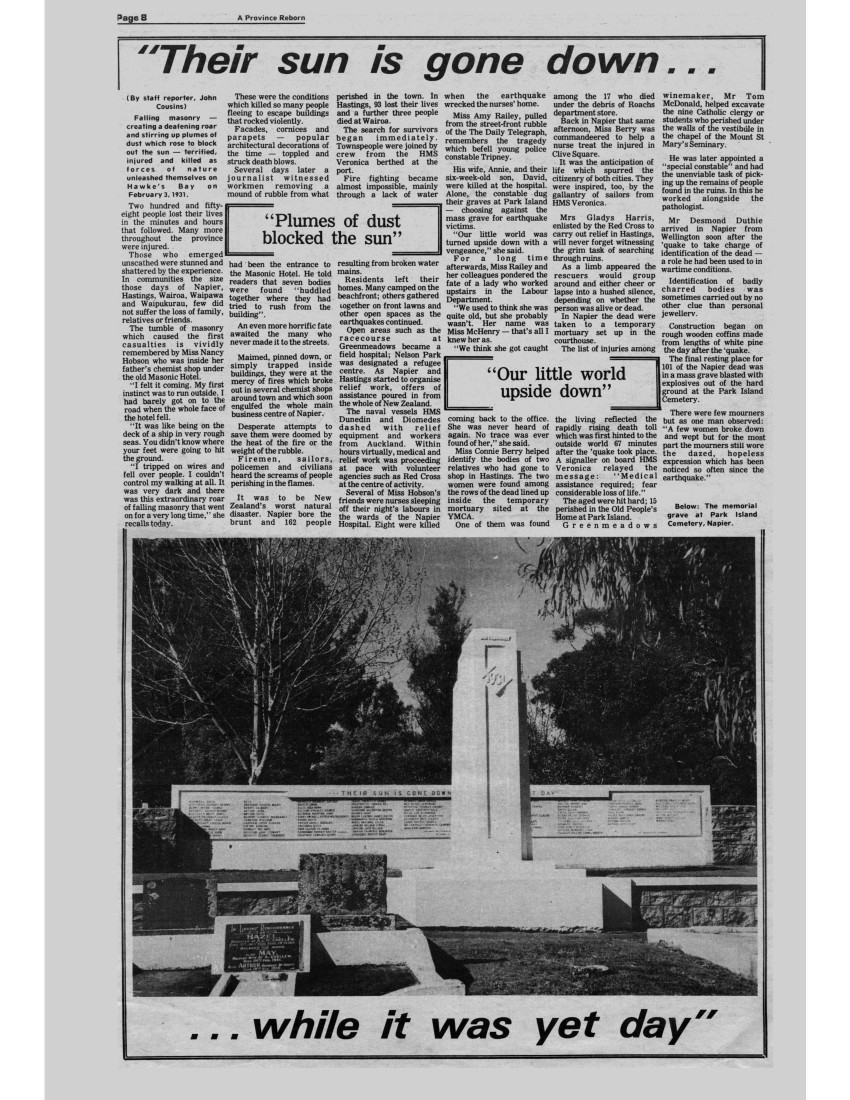

Construction began on rough wooden coffins made from lengths of white pine the day after the ‘quake.

The final resting place for 101 of the Napier dead was in a mass grave blasted with explosives out of the hard ground at Park Island Cemetery.

There were few mourners but as one man observed: “A few women broke down and wept but for the most part the mourners still wore the dazed, hopeless expression which has been noticed so often since the earthquake.”

Photo caption – Below: The memorial grave at Park Island Cemetery, Napier.

…while it was yet day”

A Province Reborn Page 9

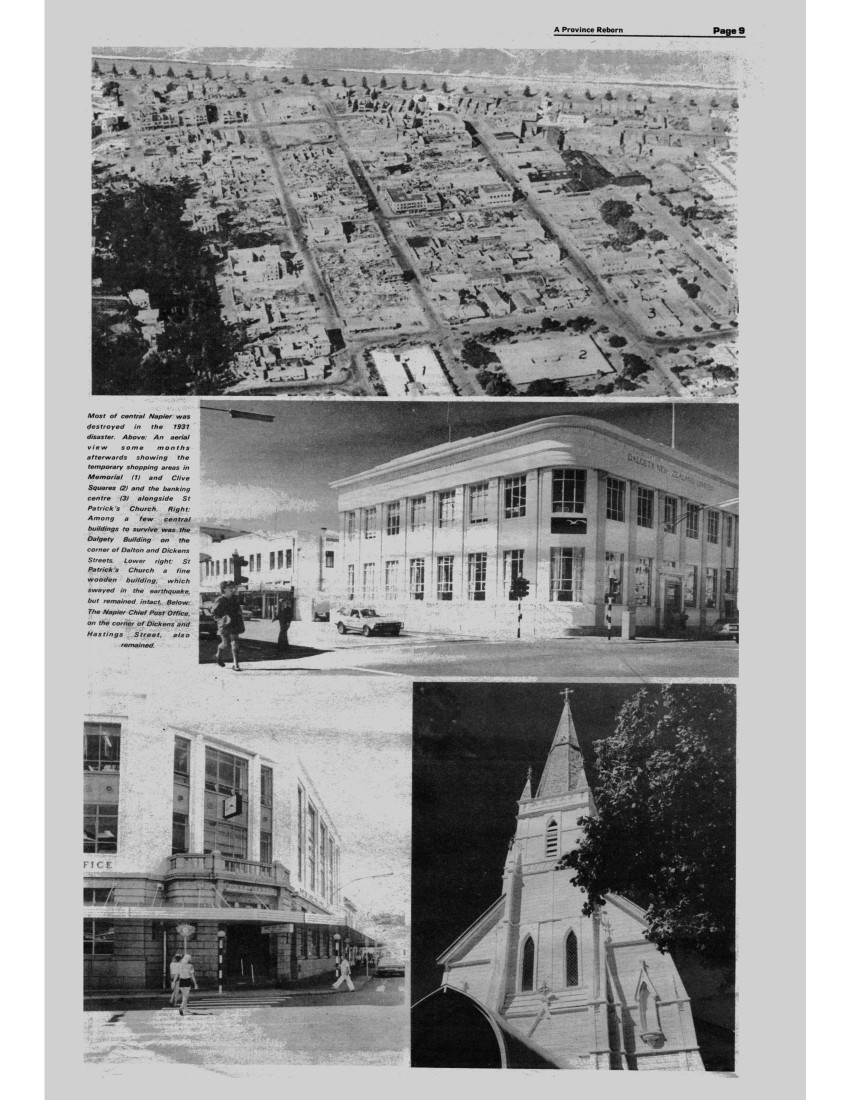

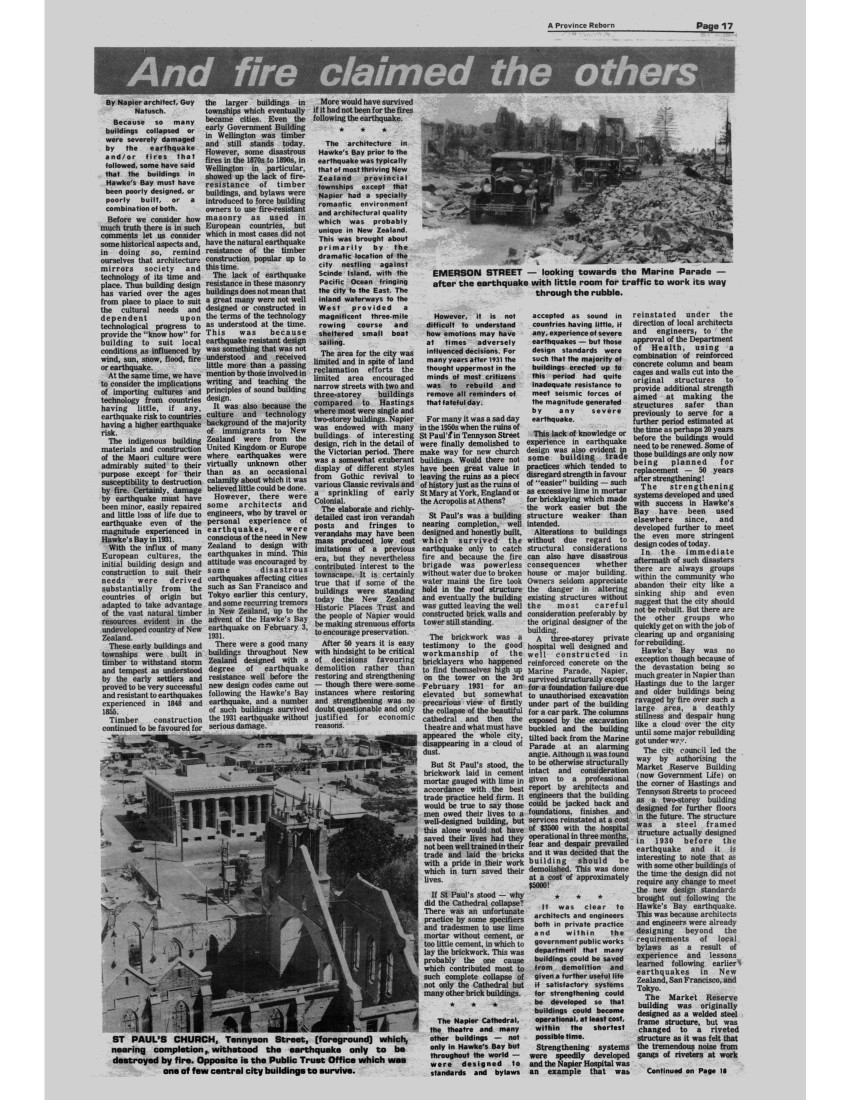

Most of central Napier was destroyed in the 1931 disaster. Above: An aerial view some months afterwards showing the temporary shopping areas in Memorial (1) and Clive Square as (2) and the banking centre (3) alongside St Patrick’s Church. Right: Among a few central buildings to survive was the Dalgety Building on the corner of Dalton and Dickens Streets. Lower right: St Patrick’s Church a fine wooden building, which swayed in the earthquake, but remained intact. Below: The Napier Chief Post Office, on the corner of Dickens and Hastings Street, also remained.

Page 10 A Province Reborn

‘Boiling mud and water bubbled from the ground’

By Daily Telegraph journalist, Craig Marsh.

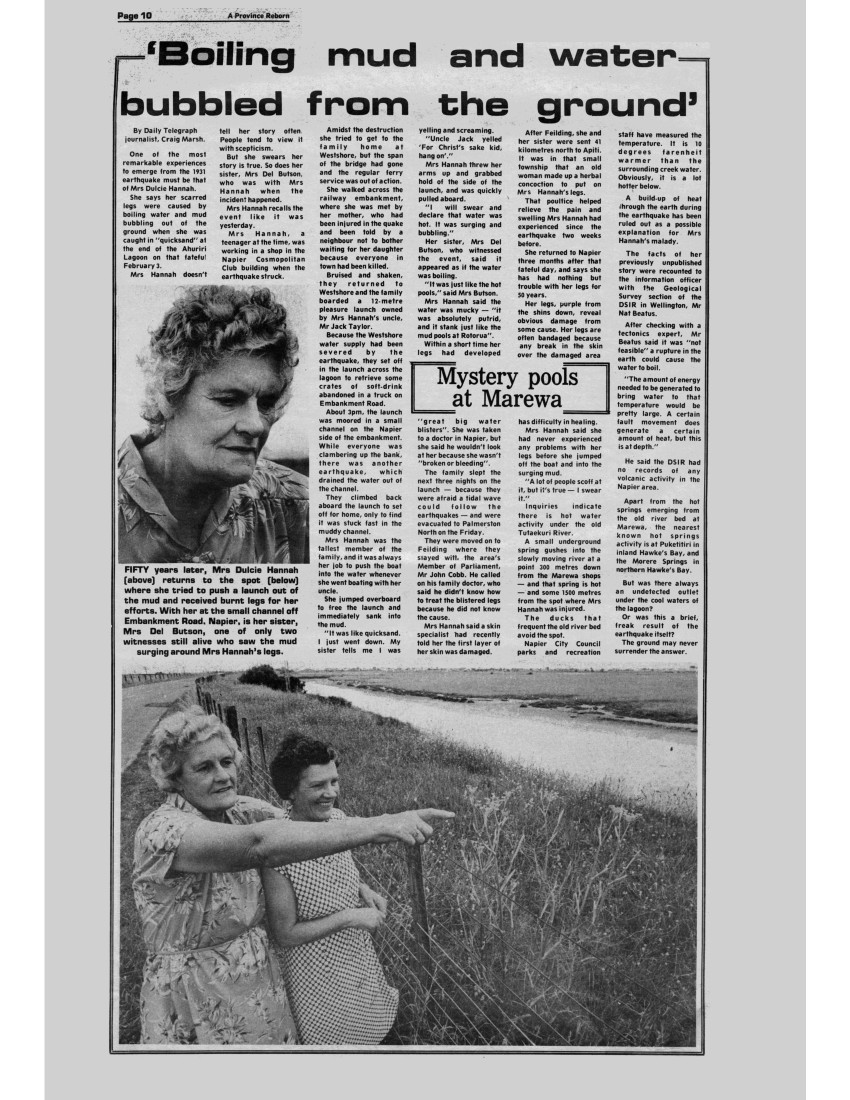

One of the most remarkable experiences to emerge from the 1931 earthquake must be that of Mrs Dulcie Hannah.

She says her scarred legs were caused by boiling water and mud bubbling out of the ground when she was caught in “quicksand” at the end of the Ahuriri Lagoon on that fateful February 3.

Mrs Hannah doesn’t tell her story often. People tend to view it with scepticism.

But she swears her story is true. So does her sister, Mrs Del Butson, who was with Mrs Hannah when the incident happened.

Mrs Hannah recalls the event like it was yesterday.

Mrs Hannah, a teenager at the time, was working in a shop in the Napier Cosmopolitan Club building when the earthquake struck.

Amidst the destruction she tried to get to the family home at Westshore, but the span of the bridge had gone and the regular ferry service was out of action.

She walked across the railway embankment, where she was met by her mother, who had been injured in the quake and been told by a neighbour not to bother waiting for her daughter because everyone in town had been killed.

Bruised and shaken, they returned to Westshore and the family boarded a 12-metre pleasure launch owned by Mrs Hannah’s uncle, Mr Jack Taylor.

Because the Westshore water supply had been severed by the earthquake, they set off in the launch across the lagoon to retrieve some crates of soft-drink abandoned in a truck on Embankment Road.

About 3pm, the launch was moored in a small channel on the Napier side of the embankment. While everyone was clambering up the bank, there was another earthquake, which drained the water out of the channel.

They climbed back aboard the launch to set off for home, only to find it was stuck fast in the muddy channel.

Mrs Hannah was the tallest member of the family, and it was always her job to push the boat into the water whenever she went boating with her uncle.

She jumped overboard to free the launch and immediately sank into the mud.

“It was like quicksand. I just went down. My sister tells me I was yelling and screaming.

“Uncle Jack yelled ‘For Christ’s sake kid, hang on’.”

Mrs Hannah threw her arms up and grabbed hold of the side of the launch, and was quickly pulled aboard.

“I will swear and declare that water was hot. It was surging and bubbling.”

Her sister, Mrs Del Butson, who witnessed the event, said it appeared as if the water was boiling.

“It was just like the hot pools,” said Mrs Butson.

Mrs Hannah said the water was mucky – “it was absolutely putrid, and it stank just like the mud pools at Rotorua”.

Within a short time her legs had developed “great big water blisters”. She was taken to a doctor in Napier, but she said he wouldn’t look at her because she wasn’t “broken or bleeding”.

Mystery pools at Marewa

The family slept the next three nights on the launch – because they were afraid a tidal wave could follow the earthquakes – and were evacuated to Palmerston North on the Friday.

They were moved on to Feilding where they stayed with the area’s Member of Parliament, Mr John Cobb. He called on his family doctor, who said he didn’t know how to treat the blistered legs because he did not know the cause.

Mrs Hannah said a skin specialist had recently told her the first layer of her skin was damaged.

After Feilding, she and her sister were sent 41 kilometres north to Apiti. It was in that small township that an old woman made up an herbal concoction to put on Mrs Hannah’s legs.

That poultice helped relieve the pain and swelling Mrs Hannah had experienced since the earthquake two weeks before.

She returned to Napier three months after that fateful day, and says she has had nothing but trouble with her legs for 50 years.

Her legs, purple from the shins down, reveal obvious damage from some cause. Her legs are often bandaged because any break in the skin over the damaged area has difficulty in healing.

Mrs Hannah said she never experience any problems with her legs before she jumped off the boat and into the surging mud.

“A lot of people scoff at it, but it’s true – I swear it.”

Inquiries indicate there is hot water activity under the old Tutaekuri River.

A small underground spring gushes into the slowly moving river at a point 300 metres down from the Marewa shops – and that spring is hot – and some 1500 metres from the spot where Mrs Hannah was injured

The ducks that frequent the old river bed avoid the spot.

Napier City Council parks and recreation staff have measured the temperature. It is 10 degrees farenheit [Fahrenheit] warmer than the surrounding creek water. Obviously, it is a lot hotter below.

A build-up of heat through the earth during the earthquake has been ruled out as a possible explanation for Mrs Hannah’s malady.

The facts of her previously unpublished story were recounted to the information officer with the Geological Survey section of the DSIR in Wellington, Mr Nat Beatus.

After checking with a tectonics expert, Mr Beatus said it was “not feasible” a rupture in the earth could cause the water to boil.

“The amount of energy needed to be generated to bring water to that temperature would be pretty large. A certain fault movement does generate a certain amount of heat, but this is at depth.”

He said the DSIR had no records of any volcanic activity in the Napier area.

Apart from the hot springs emerging from the old river bed at Marewa, the nearest known hot springs activity is at Puketitiri in inland Hawke’s Bay, and the Morere Springs in Northern Hawke’s Bay.

But was there always an undetected outlet under the cool waters of the lagoon?

Or was it a brief freak result of the earthquake itself?

The ground may never surrender the answer.

Photo caption – FIFTY years later, Mrs Dulcie Hannah [above] returns to the spot [below] where she tried to push a launch out of the mud and received burnt legs for her efforts. With her at the small channel off Embankment Road, Napier, is her sister, Mrs Del Butson, one of only two witnesses still alive who saw the mud surging around Mrs Hannah’s legs.

A Province Reborn Page 11

‘Tin Town’ bridged the gap

By Daily Telegraph staff journalist, Peter Gaston

Fifty years later, with memories fading and wounds long since healed, Hawke’s Bay’s 1931 earthquake can still provide a shock.

In today’s terms the total value of losses and damage in Napier and Hastings on that fateful February 3 represented a staggering $250 million.

And it was the business community in both cities which was forced to bear the brunt of the losses.

The burden hung like a millstone round the necks of retailers for more than 20 years. Its weight finally dragged some to a premature end.

The cost of losses and damage have been up-dated by the Bank of New South Wales’ economic division to help offer some present-day picture of the magnitude of the disaster.

While business losses (loss and damage to stock and premises) in Napier in 1931 totalled $10.6 million, the comparative cost today would be just on $170 million, or about three times the current retail turnover in the city.

Losses in Hastings amounted to $4 million, in today’s terms about $64 million.

The cost of re-constructing the 8493 houses throughout Hawke’s Bay damaged in the earthquake was $481,282 (about $8 million today).

February 3, 1931, holds special significance for the “old timers”, several of whom today are still in business. There is some truth in the suggestion they continue to measure time from that date.

Wally Ireland is one who remembers the day vividly; he cannot forget. In a few brief minutes his immediate dream of becoming a prosperous retailer was shattered – after only 1½ days in business as picture framer and art supplier.

The first tremor sent stock hurtling around his Dickens Street store; the second hurled him bodily into the street and, as he lay “paralysed” in the convulsing roadway, Napier’s thriving retail area collapsed. Ravaging fire soon added its acrid touch to the scene of the carnage.

Noel Reading’s family, who lived above the family bakery in Emerson Street, was left with only 18c after the earthquake.

His father, the late Mr W. T. C. Reading, was rescued by Loo Kee, an Emerson Street greengrocer, after a brick wall collapsed. Loo Kee’s business was later taken over by Mr Albert Young.

In Hastings Street, L. S. McClurg, whose family still operates a jewellery shop there, lost everything and Neville Harston watched helplessly as fire consumed $80,000 worth of pianos and other musical instruments and the company records in another Hastings Street store.

The front section of Harston’s building, which was built to specifications prepared after the disastrous Murchison earthquake, withstood the earthquake but the back section was destroyed.

They had planned to rebuild the back section of the building after the earthquake but someone stole the bricks before construction started.

The story of losses both in the earthquake and ensuing fires was repeated throughout the entire city.

Tom and Jack Ringland (now operated by Jack Sadler) were burnt out of their Hastings Street premises. They rebuilt their retail store.

Blythes, which became Haywrights and later DIC, were re-constructed on the same Emerson Street site and McGruers were re-built on a site formerly occupied by Ross and Glendenning’s warehouse.

Business records became of paramount importance in the days and months after the earthquake because firms, unable to prove their solvency on the day of the earthquake, were debarred from assistance.

The loss of bank records added further complications to the business world and several businessmen, even today, adamantly claim they repaid pre-earthquake mortgages twice.

In the business heart of Napier only a few buildings of consequence survived the earthquake.

Unfortunately, the disaster occurred at a time of depression. The Government’s grants amounted to about a fifth of the estimated total losses in Napier and Hastings, though it did make some loan concessions in later years.

Although loan monies, through the Napier Rehabilitation Committee, were made available to businessmen for the re-establishment of the retail area, it was generally not enough.

One borrower, who needed $150,000 to re-build and another $26,000 for stock, received a loan for only $39,000.

It was the support Napier received from the wholesale industry that played an important part in the restoration of the business sector.

Wholesalers and other large business interests in other areas of the country rallied around and while they were not always able to provide monetary aid, help was given in other forms.

Fittings and display cases from Wellington assisted Arthur Spackman and Arthur Hobson re-establish their chemist shops in Emerson and Hastings Streets.

Cox’s Menswear, operated by Martin Kilpatrick and Frank Fenton, was burnt out in Hastings Street but with the help of loans they re-established themselves in “Tin Town” and then moved to a site in Emerson Street, which subsequently has been used for the Broadlands Mall.

While in the first weeks after the earthquake efforts were concentrated on restoring essential services and repairing homes there was little help for the businessman.

Some optimistically opened in undamaged backrooms, erected their own temporary premises on their devastated sites. The first tangible sign of returning the retail section to normal came with a $20,000 loan from the Government for the erection, by the Fletcher Construction Company, of temporary premises in Clive Square.

And on March 16, nearly six weeks after the disaster, Tin Town was opened.

The actual re-construction of the business area was delayed while planners widened the three major streets, Tennyson, Emerson and Dickens Streets and added service lanes in the business area.

Reconstruction was slow and costly. By March 1932 only 19 shops were ready for occupation but by the end of the year another 130 were nearing completion or had already re-opened.

The re-building of Napier was the greatest programme of concentrated building New Zealand had ever seen and in the first two years after the earthquake permits for the construction of new buildings worth nearly $1.6 million were issued.

The first new permanent buildings to be completed after the earthquake was Barrys Bottling Co. Ltd’s Wellesley Road premises and one of the first businesses re-established in the inner-city area was Canning and Loudon’s Tennyson Street garage.

The Masonic Hotel opened for bar trade in December 1932, and Hector McGregor Ltd was also operating from new premises at about the same time.

By January 1933, 108 shops in the new Napier had been completed, 21 were still unoccupied and 43 under construction.

By 1940, as New Zealand clawed itself out of the depths of the depression and into the grasps of a major world conflict, the rebuilding of Napier was virtually completed.

After being restricted to eight streets at the time of the earthquake, Napier’s business centre has begun to expand into Raffles and Vautier Streets with office blocks rising in what was once residential areas.

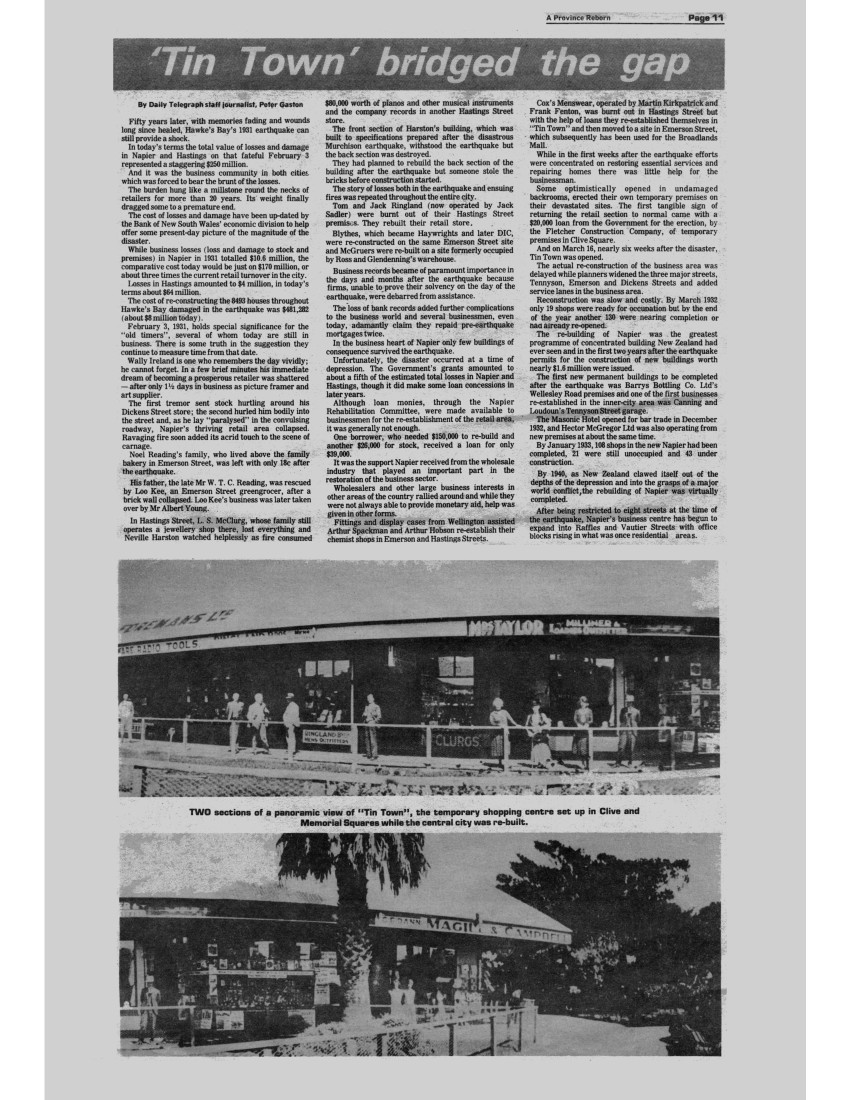

TWO sections of a panoramic view of “Tin Town”, the temporary shopping centre set up in Clive and Memorial Squares while the central city was re-built.

Page 12 A Province Reborn A Province Reborn Page 13

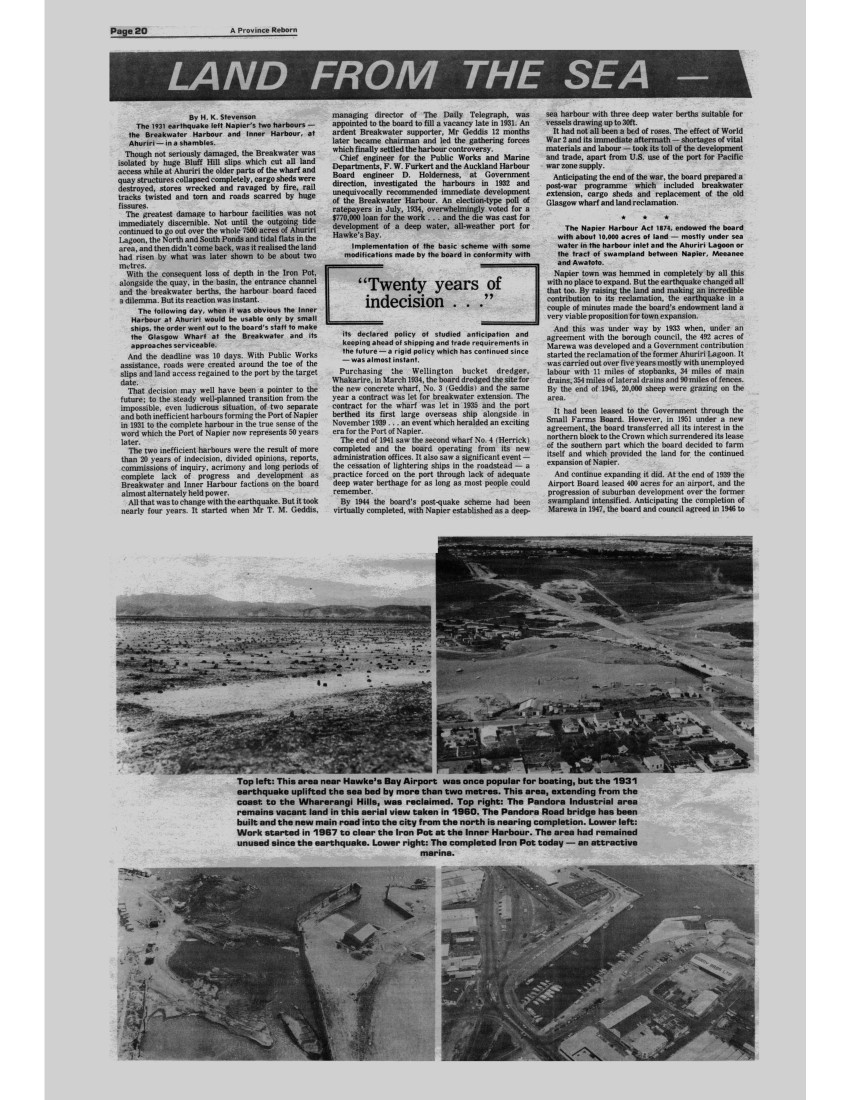

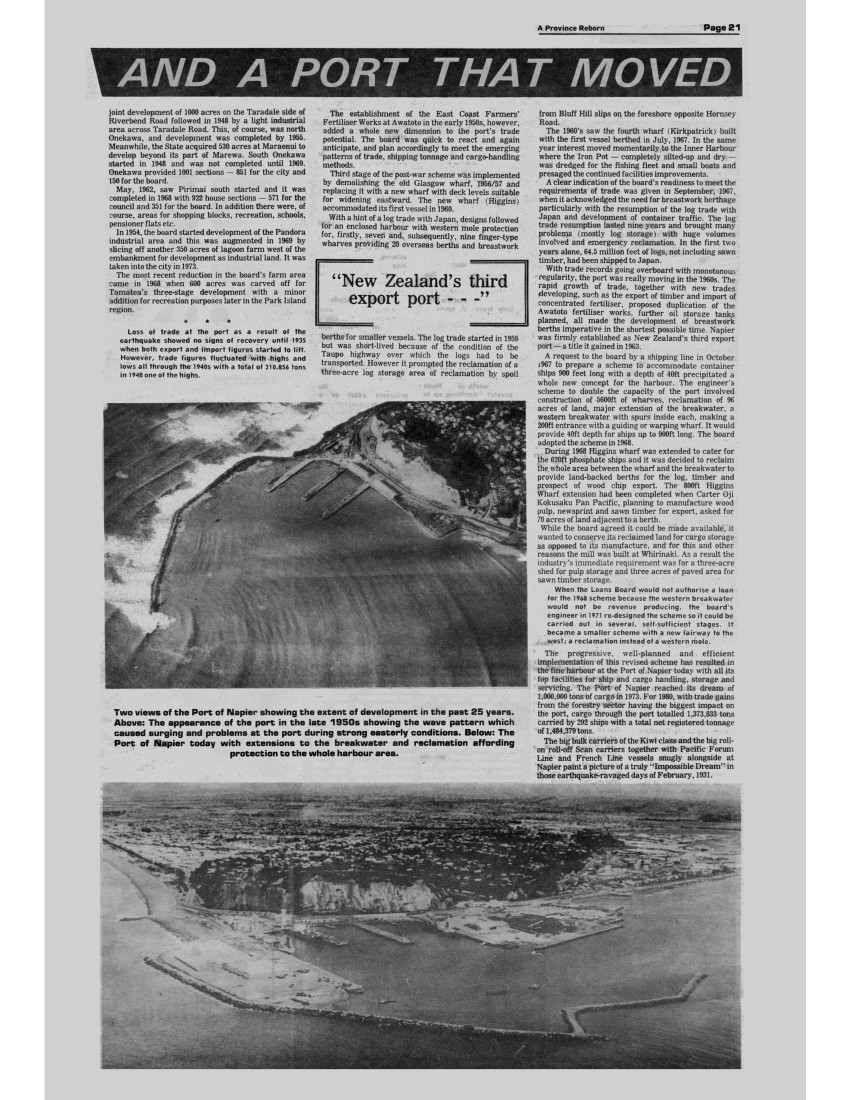

Thousands of acres of land were uplifted from the sea floor in the 1931 earthquake.

Beneath the glider, soaring against a backdrop of Napier and the Heretaunga Plains, is the land which became available for Hawke’s Bay Airport, and for farming, industrial and residential development. After 1931, gone were the days of this as a popular boating and recreational area.

Page 14 A Province Reborn

Napier’s urban growth

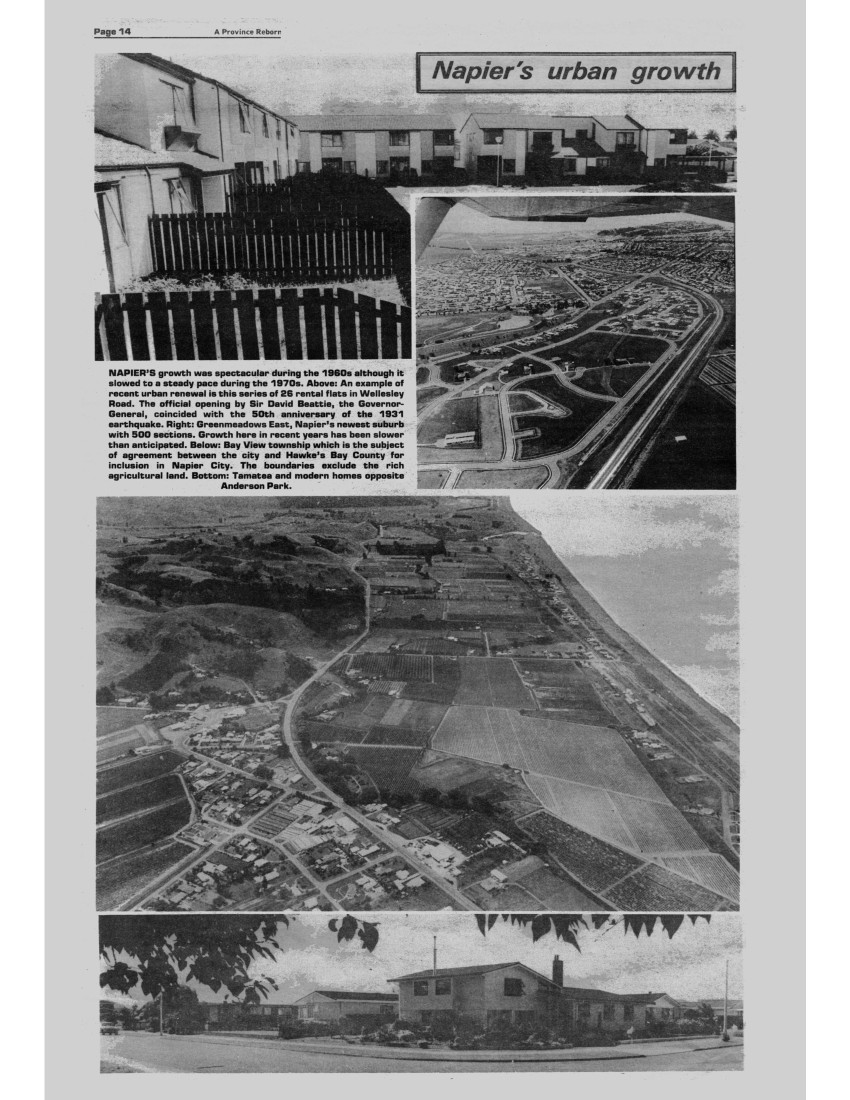

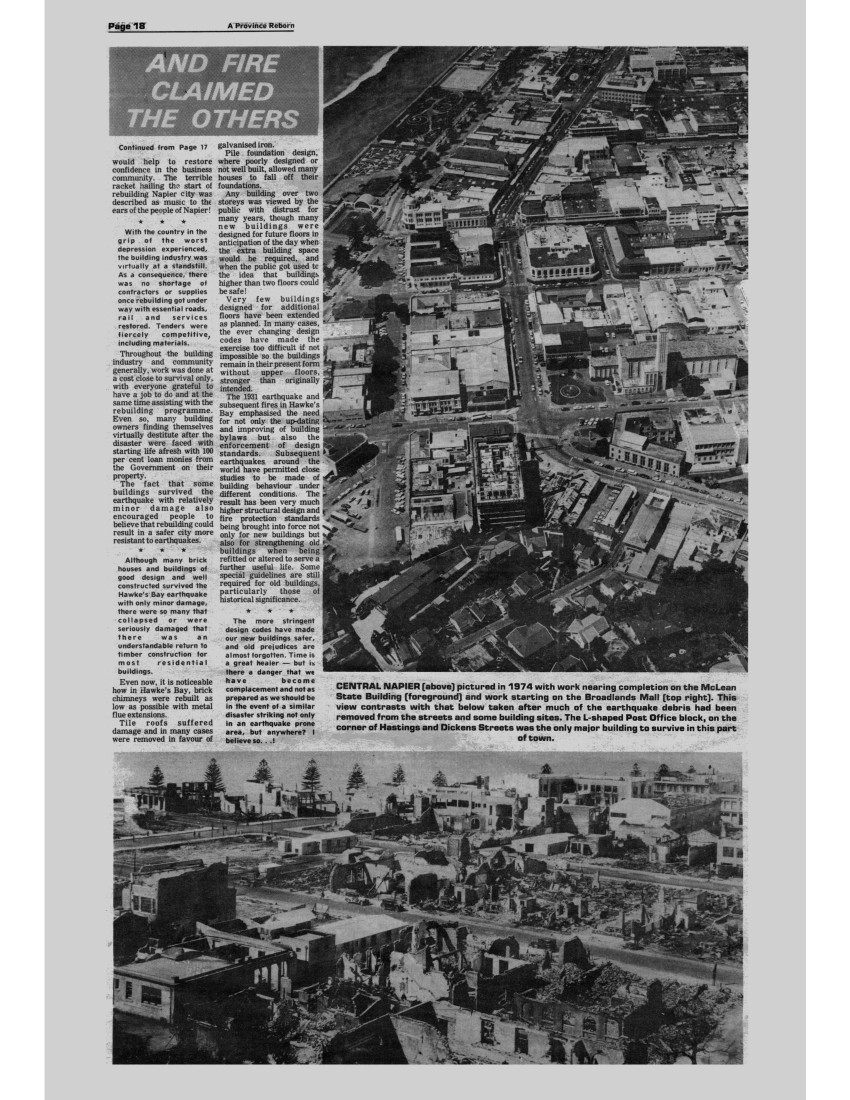

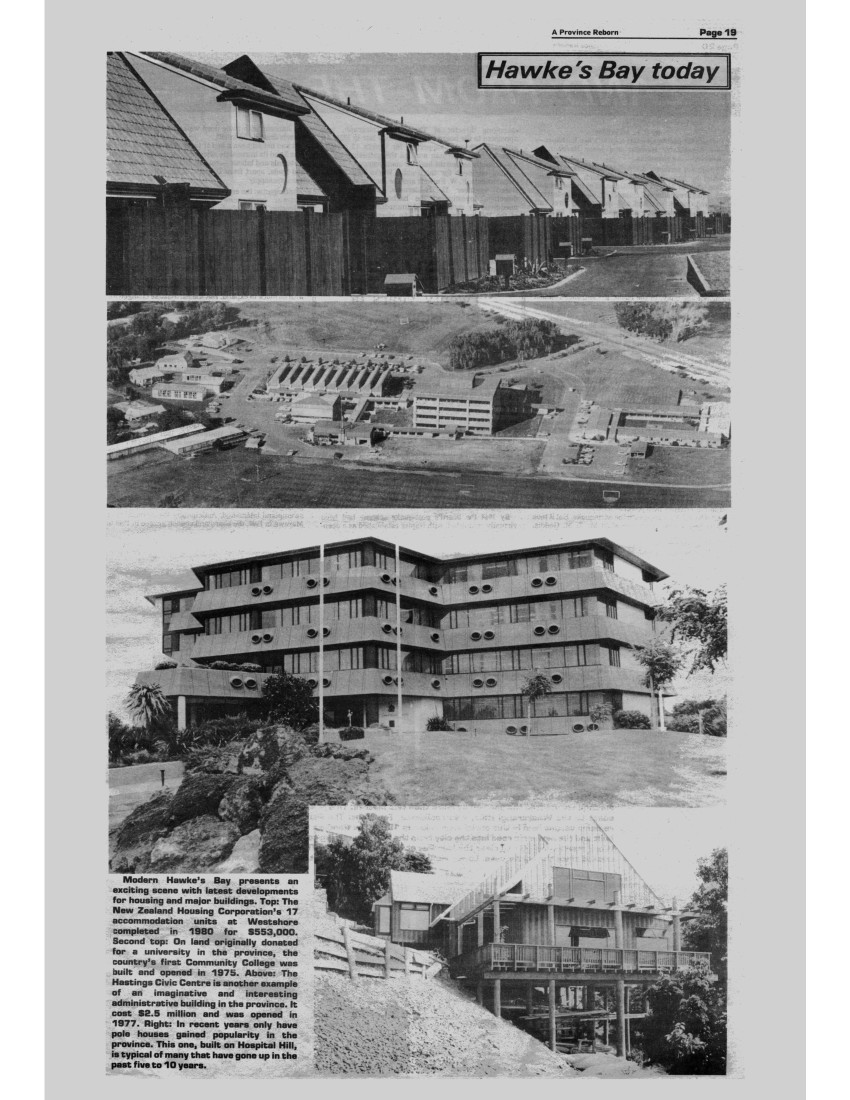

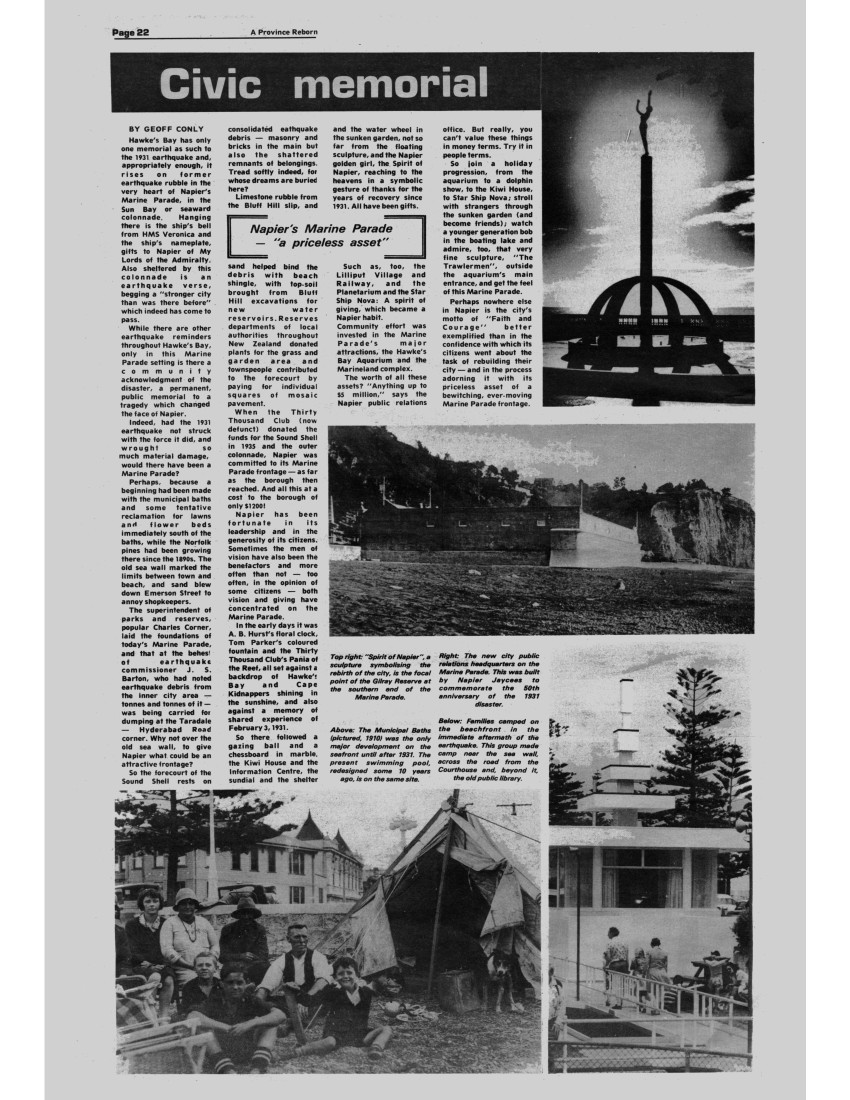

NAPIER’S growth was spectacular during the 1960s although it slowed to a steady pace during the 1970s. Above: An example of recent urban renewal is this series of 26 rental flats in Wellesley Road. The official opening by Sir David Beattie, the Governor-General, coincided with the 50th anniversary of the 1931 earthquake. Right: Greenmeadows East, Napier’s newest suburb with 500 sections. Growth here in recent years has been slower than anticipated. Below: Bay View township which is the subject of agreement between the city and Hawke’s Bay County for inclusion in Napier City. The boundaries exclude the rich agricultural land. Bottom: Tamatea and modern homes opposite Anderson Park.

New course for progress

Daily Telegraph civic reporter CRAIG MARSH traces development on the Heretaunga Plains in the 50 years since the earthquake, highlighting the often spectacular growth of Napier and Hastings in the wake of the country’s worst disaster.

Napier’s tragic destruction was also its salvation.

For nearly 80 years beforehand the town had been caught in a land famine which restricted expansion beyond boundaries severely limited by water and swamp.

By 1925, Napier could not have grown more without enormous sums of money for reclamation. Thus, with the violent upheaval of 2800ha of the lagoon area and the improvement of a further 1100ha, Napier’s future was virtually unlimited.

After 1931, Napier began to expand in earnest: A definite town planning process sprang into being: The land famine which had threatened Napier was over.

Engineers diverted the Tutaekuri River to a new course to reduce the danger of floods, opening up a massive new area of safe land for housing and industry.

Three years after the disaster, the Napier Harbour Board – which had a windfall with the massive land inheritance – agreed to lease a block of 190ha to the then Napier Borough Council.

The development of that area (Marewa) began in July, 1934, with the construction of a bridge over the old Tutaekuri River and extensions to Kennedy and Taradale Roads. By May, 1935, most sections had been leased.

Although this area was extended in 1936 with the inclusion of Marewa South, Napier’s housing shortage remained serious. This was partly relieved by the setting-up of the Housing Corporation branch of the State Advances Corporation in 1937.

Roads were another of the problems besetting the borough’s expansion. Until the completion of tar-sealing during the 1950s, streets were usually dusty in summer and boggy in winter.

Roading was just one of Marewa’s early problems. As an early settlement in the southern expansion of Napier, it was a pioneer State housing ara, complicated by joint administration between county and borough councils.

Although it was the only substantial new housing area developed during the 1930s and 1940s, village settlements were established on harbour board land.

One of these settlements was at the Richmond Block – now Maraenui.

Encouraged by the cluster of cottages and good crop expectations, the Government made plans to reclaim part of the Ahuriri Lagoon for more settlements, designed for 300 families.

As well as new farms, the former Inner Harbour – lagoon area provided new airport sites for Napier. Planning for an airport had been under way as early as 1929 when the Napier Aero Club was formed.

In 1932 the club obtained a lease of 45ha along the Napier-Westshore embankment. Club labour worked the rugged terrain to such a high standard that the Gisborne-based east Coast Airways started its Gisborne-Napier service three years later.

Within a short time a lease of the area now known as Beacons was obtained and this was eventually chosen as Napier’s chief airport, until it “went into recess’ at the outbreak of war in 1939.

It would be another 18 years before the Civil Aviation Administration confirmed the Beacons as Hawke’s Bay airport.

Even then, local rivalries would delay its development for another four years. Hastings’ interests argued a better site existed at Bridge Pa, a few kilometres south-west of Hastings.

Officially opened in 1964, the Hawke’s Bay Airport soon rose to sixth place in New Zealand’s air freight and passenger trade.

The decade following the earthquake was also an important period for the development of Napier’s parks and reserves. Forward thinking during this time provided Napier with what are now some of its finest assets – its parks.

‘Finest assets’

Some, damaged by the earthquake, were restored to their former condition, while others were added to the borough.

Nelson Park and McLean Park, carefully drained and re-sown, had returned to their pre-1931 quality by the end of 1939.

In 1937 the council leased 1.2ha of land in Napier South and called it Kennedy Park. The area quickly developed into a popular camping ground, and a further five hectares were added in 1942.

At Port Ahuriri, the reclamation of eight hectares of land at South Pond started in 1939. By the end of the war, enough ground had been prepared for one football field.

Protracted negotiations between the harbour board and the council ended in 1945 with the release of 420ha for housing under the council’s control. These areas are now the fully-developed suburbs of Onekawa and Pirimai.

A block of 146ha between the embankment and the present Hyderabad-Pandora Roads was also reserved for future industrial development. This agreement meant a new era of progress for Napier.

In January, 1949, the first sections in the new suburb of Onekawa were sold to prospective home-builders.

Napier people took pride in their town’s elevation to city status in March, 1950. The city enjoyed a fair measure of prosperity during the next five years, and the acute housing shortage slowly improved in the latter half of the decade – a difficult economic time for the country.

Urbanisation had proceeded rapidly after the war. By 1945 half of the region’s population lived in metropolitan Napier and Hastings. But by 1966, 60 per cent lived in the two centres, and three out of four Hawke’s Bay residents were town dwellers.

The expanding urban population in Napier needed housing, and two years after development began at Onekawa, the Ministry of Works negotiated the purchase of freehold and leasehold interests in the Richmond Block.

This provided a new residential area of 94ha, with nearly 900 sections available for an estimated 4000 people. Then in March, 1955, the council borrowed more than 100,000 pounds to develop roading, sewerage, drainage and other services in the new suburb of Maraenui.

Another Onekawa block of 113ha, west of Taradale Road and zoned for light industry and warehouses, became part of Napier City in 1958. This was where Napier would experience its rapid industrial development in later years.

The economic recovery of the early 1960s saw increases in housing targets, and the new suburb of Pirimai was developed. For the next six years Napier builders flourished as families moved into the new housing areas of Onekawa South, Maraenui and Pirimai.

As well as its development of Kennedy Park, the city council developed new parks for the city’s growing population. In 1957 it acquired Whitmore Park, and four years later the parks and reserves staff began the development of Onekawa Park (both eight hectares).

Shortly after, Anderson Park (34ha) and Pirimai Park (2.5ha) were added to the impressive list of parks and reserves.

In terms of residential expansion, Napier enjoyed an advantage over its sister city Hastings, whose rich farming hinterland restricted its growth on all sides.

In addition, Napier gained more than 400ha and 6300 people when it absorbed the borough of Taradale. This merger had been considered as early as 1948. Amalgamation took place in 1968.

A year earlier, an area of 240ha was transferred from the county to Napier city. Originally called the Wharerangi block, the development of Tamatea began two years later, rising to the present 2000 households.

The boom period of the early 1970s also resulted in the planning of a satellite city on the nearby Wharerangi Hills. Originally planned for a city of 25,000 people by the 1980s, but later a suburb of more modest proportions, the proposal fell through with the subsequent downturn in the economy and a drop in demand for sections.

‘Boom period’