- Home

- Collections

- COLWILL VM

- 1931 Earthquake

- NZ Free Lance Earthquake Report 1931

NZ Free Lance Earthquake Report 1931

NEW ZEALAND

FREE LANCE

31ST YEAR OF ISSUE – NO. 33. WELLINGTON, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 1931. NINEPENCE

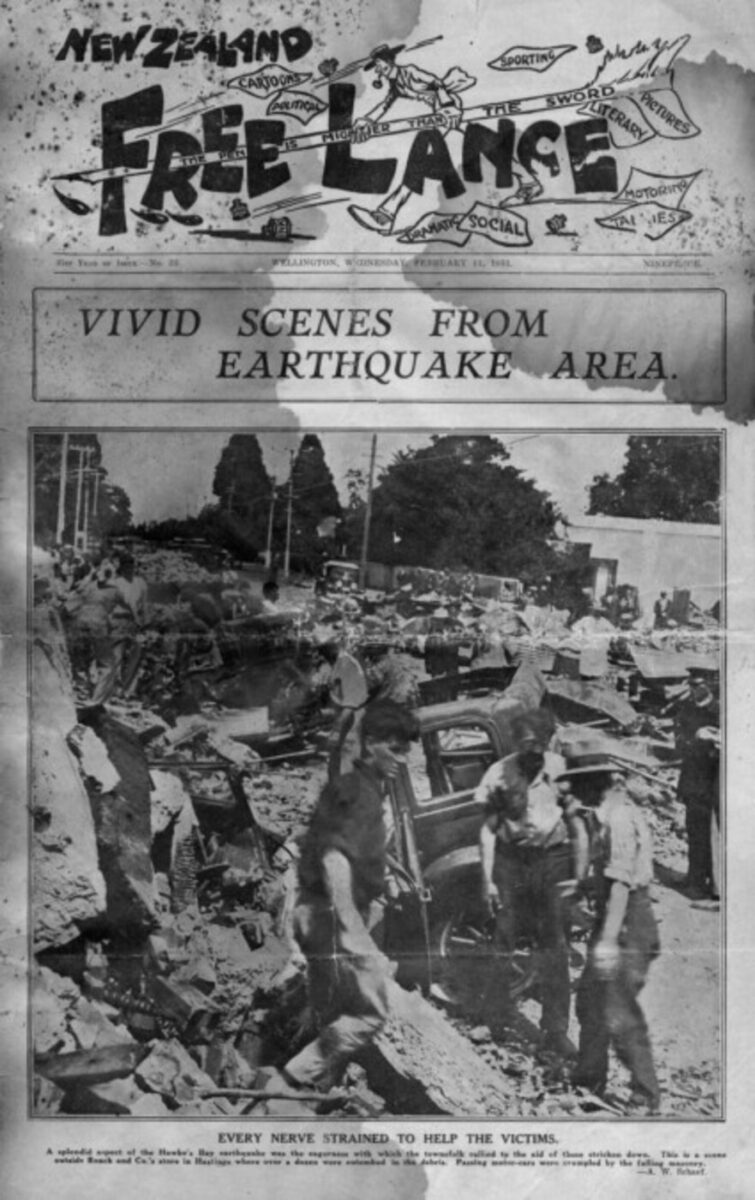

VIVID SCENES FROM EARTHQUAKE AREA.

EVERY NERVE STRAINED TO HELP THE VICTIMS.

A splendid aspect of the Hawke’s Bay earthquake was the eagerness with which the townsfolk rallied to the aid of those stricken down. This is the scene outside Roach and Co.’s store in Hastings where over a dozen were entombed in the debris. Passing motorcars were crumpled by the falling masonry. – A.W. Schaef.

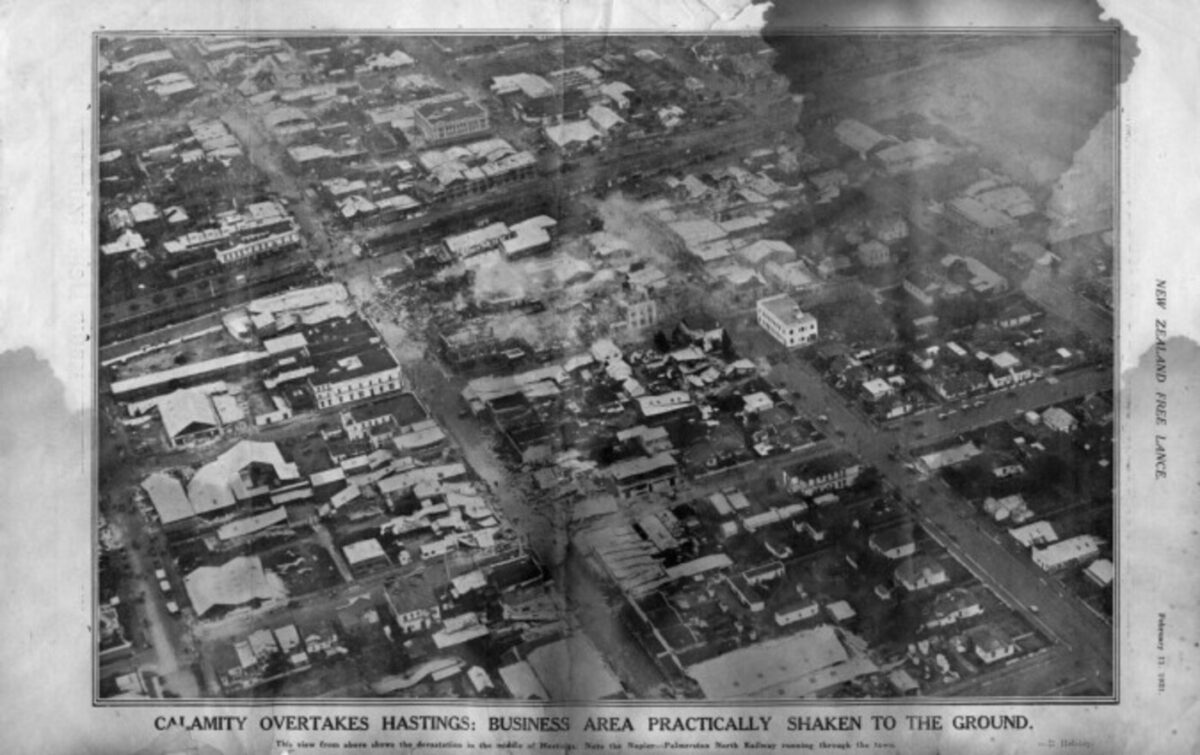

4 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

Hawke’s Bay Hour of Trial.

Napier and Hastings Wrecked by Earthquake.

TERRIFYING EXPERIENCES AMID TUMBLING MASONRY.

CASUALTY LISTS INCLUDE NEARLY THREE HUNDRED DEAD AND OVER A THOUSAND INJURED.

By Our Special Reporters in the Earthquake Area.

THE hands stood at twelve minutes to 11 am by the Marine Parade clock at Napier on Tuesday, February 3, when the earthquake struck the towns of Napier and Hastings, and, in lesser degree, the whole of that East Coast region of the North Island, with the suddenness of a thunderclap. The business areas of both towns were reduced to ruins. Whole streets of brick and concrete buildings collapsed like a pack of cards. Roofs fell in, walls crumbled into masses of debris, and then fires broke out and raged furiously to complete the work of destruction.

As soon as news of the calamity reached Wellington, special reporters and photographers were despatched by the “New Zealand Free Lance” per motor-car to Napier and Hastings. The photos and the descriptive accounts which they furnish tell their own tale. The general effect is vividly described in the words of sufferers with whom the “New Zealand Freelance” spoke while the terror still haunted their eyes.

BLOW STRIKES HASTINGS

“I was taking change from the cashier”, said an employee of a Hastings place of business “when the earth surged up beneath us. All sense of balance was destroyed. We grabbed each other, and fell helpless to the floor. Instantaneously the building began to disintegrate around us. The grinding, pulverised walls blinded us with dust. l tried to shout through the crashing: “Archway!” and we fought our way to it. Others were there; one lad screaming. I could see him, but his poor little voice did not sound above the roar. We sometimes saw openings appear in the outer walls, and tried to reach them, but debris from above filled them up, and we were bruised and bleeding when we got back to the archway. But at last we burst through-some of us. As we ran across the pavement of Heretaunga Street – Hastings’ leading thoroughfare – we saw a woman struggling with three terror-stricken children, one in a pram. A heavy piece of masonry killed one. A piece of concrete the size of a bag of cement fell on the pram, and the carriage and infant were crushed flat. The woman screamed as if demented. People hurried her on to the road.”

NAPIER’S TERROR.

“I’M a cobbler,” said a lame man. ‘ “Worked at Thorp’s bootshop (Napier). Those red-hot bricks are all that’s left of it. Caught me like a battering ram in the back. My mate got as far as the door, when the building crushed him flat. My bench is strong, and I got my head and shoulders under it. My legs were out, and my wooden one was broken. Yes, lost it in the war. Bombardments and real earthquakes are the same. A tremendous movement and concussion in which most of the damage is done, and then quivering. It seemed hours that I was there with the smoke of the approaching fire in my nostrils. Then I heard my boss’s voice. Ever been buried by a barrage and heard your mates digging you out?”

Telling Facts.

THOUGH the earthquake shook the Whole of New Zealand, damage was practically confined to Hawke’s Bay where seven towns and a hundred smaller settlements were affected.

One hundred and twenty people were killed in Hastings; up to the time of writing 103 dead had been officially reported at Napier, while about fifty deaths occurred elsewhere.

Injured people to the number of 1,500 passed through the Napier field hospital, while over a hundred serious cases alone were handled at Hastings.

Napier Borough, Taradale Town District, and remainder of urban area had a population of 19,220.

Hastings Borough, Havelock North Town District and remainder of urban area had a population of 15,930.

Hastings had a capital value (land and improvements) of £3,482,100, and Napier £4,512,040.

£3,000,000 may not cover the total damage in Napier and Hastings alone. Five million pounds may easily prove the total cost to the province. The State Fire Office has given a lead by deciding to make ex gratia payments at the direction of the general manager to policy-holders whose insured property has suffered fire damage.

Mrs. Vida Short, a typical Napier householder of the business area, told our reporter that she lived in a Dickens Street flat. She had just finished scrubbing, and was about to take a bath when the blow fell. “Our building just held together till we got out. We fought our way past falling buildings to a little clear section. There must have been hundreds there. We held hands to retain our balance. When the convulsion was over some women said: ‘We should erect a memorial tablet to this vacant section in commemoration of our deliverance.’ But as soon as the first shock was over we hurried to places of greater security. We had seen people emerging from crumbling business houses and dashing through showers of bricks and mortar for the Marine Parade, and we followed. Scenes of mental agony replaced the terror which I think everybody felt While the shocks continued. Mothers cried for their children; children for their parents.”

A FUNERAL PYRE.

FROM the dust-covered ruins a more ominous haze soon commenced to rise. Fire broke out at the Masonic Hotel, the leading hotel of Napier, and at various other places. Beneath the ruins of the entire business section of a town of 20,000 people lay many stunned, others just able to call for assistance, and a few in full exercise of their strength fighting like trapped animals for escape. But the flames spread rapidly, and by noon, a pall covered the city; beneath it the fire raged. How many people perished it may take days still to ascertain.

Some died within an ace of escape. While our reporter looked on, four policemen shifted a few bricks, rolled the charred body of a woman on to a blanket and carried her to the morgue. Others were pinned, but rescued in time. One lady was crushed in a church without possibility of escape. With broken mains, and unable even to reach the sea, the fire brigade – a pigmy fighting a giant – was doubly helpless in that area.

AT NAPIER HOSPITAL.

THE earthquake was felt with special severity and had terrible heartrending effects at the Napier Public Hospital and Nurses’ Home. At the Hospital the operating theatres as well as the ten wards were full. Two operations had just been concluded when the crash of the quake shook the buildings to its foundations. The patients were removed to safety, and, before he realised what was happening one of the surgeons had dashed back to recover his collar and tie.

Throughout the crowded institution the staff lived up to the finest traditions of humanitarian work. In the women’s medical ward the most tragic events occurred. As an eye witness of the holocaust told the “New Zealand Free Lance” that the 32 beds were full. The sisters stood by them till the wall fell out and the roof fell in, killing the majority of those beneath. Another badly hit section was the isolation ward, which crumpled up like a match-box.

The Nurses’ Story.

The comparatively new Nurses’ Home proved a veritable death trap. It was occupied at the time of the tragedy by office, kitchen and night staff. Amongst the latter were Nurses J. Palairet, E. Liken, M. Coleman, E. Horton, M. Bowling, and H. Alpin, from whom the “New Zealand Free Lance” received a graphic outline of their experiences. The first concussion, they said, threw the night sister, still in bed, out of the second story window and over a hedge. She landed without serious injury. Most of the rest were trapped.

The Hospital Chief’s Experience.

Discussing the medical phase of the event, on Wednesday, Dr. A. C. Biggs of the Napier Hospital, rubbed 36 hours of sleeplessness from his eyes and said: “The rush of casualties was first met by a dressing station for serious cases in the Botanical Gardens. With the increasing volume of injured we opened a clearing station at Napier Park Racecourse where the principal forces of the hospital were re-assembled and reinforced by doctors and nurses from Gisborne in the north to Wellington in the south. At one time we had four operating theatres going at once, and before the rush was over had handled between three and four hundred casualties. The medical staff did not sleep and ate little during that time, and it is only now that we have been able to organise relays in certain branches of the medical and assistant services.”

Wellington was well represented amongst the relief doctors and ambulance men. One of the latter told the “New Zealand Free Lance” that he was on the job a little more than twelve hours after the visitation. “And would you believe it: after coming all this way expecting to treat serious injuries, our services were first requisitioned in a maternity case. We have brought hundreds out here. A tough chap who had his hand taken off, woke up laughing at the doctor and saying, ‘Well, sir, you won’t have the nerve to charge me for that, will you?!

Besides the despatch of the injured there was the assembly of the dead in morgues. One was the battered Courthouse, into which our reporter penetrated. The first batch of bodies – some fourteen – lay in bloody sheets and blankets

NINE KILLED IN CHAPEL.

No losses touched so many hearts, and in no place did more dead lie to the square yard, than in that ecclesiastical architecture the chapel at the Marist Fathers’ Seminary at Greenmeadows.

Two young students rose from the laying out of a dead comrade’s body as our reporter arrived, and they accompanied him within the stark walls.

One of them told this brief story. “There were 33 of us, all in chapel; four of us Australians. I have never been in an earthquake and had not appreciated the necessity for getting outside. Instead I turned to the wall, when the dreadful shock came, and those who did were saved. Those who tried to get out were killed.

The other student said: “It was terrible. Blinding dust accompanied the tremendous shock. We could see but dimly through the haze. All we could hear was the crashing of the masonry around us. Three boys knelt below the organ, and in doing so escaped death. Then the sanctuary arch fell, the back wall opened and they ran out unhurt from the shattered church. Several boys were crushed at the entrance. Others fell, and were helped out by the rest. Later we went back for those buried, but so terrible were their injuries that they must have died immediately.”

The writer looked at the blood of seven students, two priests and a number of seriously injured splashed upon the sacred floor, and moved outside. There, all the hill on which

Earthquake Relief Fund.

A SUBSCRIPTION list in aid of the above Fund has been opened at the “New Zealand Free Lance” office headed by a contribution of £50 from the Proprietors, which was remitted on Thursday last to His Worship the Mayor of Wellington. All donations received will similarly be sent on.

At the time of writing the amount subscribed in Wellington alone totalled well over £20,000.

CROWDED OUT.

Owing to pressure upon our space to afford the utmost room for the earthquake narrative, several of the “New Zealand Free Lance’s” usual features have had to be held over.

Photo caption – WELCOME AID. – Very soon after the disaster a large party of Maoris was organised to help in the rescue work. – C.F. Newham.

February 11, 1931 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 5

the Seminary stood was still slipping with the successive shocks. This extensive movement accompanying the shake had almost irreparably damaged the old building, and crumpled the bottom story of the new like cardboard without even breaking a pane of glass in the two top floors.

The death roll at the Seminary consisted of Father Gondringer (parish priest of Hastings), Father Boyle (business manager of the institution), William Stevenson (Mosgiel), James Doogan (Greymouth), Bodey Anisy [Ainsley] (Greymouth), Vincent Carmody (Wanganui), Ngaio Rafter (Wellington), Leonard Mangos (Timaru) and Alec Devonport (Christchurch). Father Gondringer was formerly a leading member of St. Patrick’s College staff in Wellington. Rafter was an athlete and ran particularly well in the distance events at the last secondary school sports. He was the oldest son of Mr. and Mrs. Rafter, of Brooklyn, Wellington, and was educated at the Marist Brothers’ School, Wellington South, and subsequently at St. Patrick’s College.

HOW THE SCHOOLS FARED.

THE majority of schools in the district had commenced the new year’s work only a couple of hours when the crash came, and many pupils fell to rise no more. Children, however, form a lower percentage of the casualties than might have been the case had not the play hour intervened in many instances. “At Havelock North,” said an orchardist’s child to our reporter, “over a hundred of us were in the baths. The water was thrown about as if you tilted a tub, and all the dressing rooms were flooded,”

Jack Short, of the Napier Boys’ High School, said. “With the exception of new boys who were being interviewed inside and may have been injured, the scholars were standing at ease on the parade ground. The Sergeant-Major told us to make for home, but many of our bikes had been destroyed”

”The Technical College caught it badly. Many of the scholars were upstairs; some shifting furniture from the old school to the new,‘The Tech.’ Queen is reported missing. Rumour says that up to a score of pupils lie amongst the ruins but who can tell until the bricks and timbers are cleared?” Most remarkable to those who stood round that shapeless mass of Technical School debris is the fact that rescue was affected even 36 hours after the impact. The sailors who worked on the “Tech” till they literally dropped deserved the reward they received for their sustained efforts. Conscription of sight-seers as auxiliaries to sailors, police, navvies and volunteer citizens might have saved one or two more lives

COURAGE IN CALAMITY.

DASHING through from Napier to Wellington last Wednesday came a sky-blue car with “Special – Royal Mail – Napier” pasted on the windscreen and bearing some 700 telegrams and letters, the first batch of personal messages from the devastated area. Written on bits of brown paper, on telegraph forms, on leaves from notebooks, they were entrusted by the P and T Department to the driver, Mr S. Thorpe, of Wellington.

Leaving Napier at 9.30 a.m., he arrived in Wellington at nightfall, weary and blood-stained from rescue work.

In Napier on business for his firm, London Distributors Ltd., Mr. Thorpe was driving down the hill from Shakespeare Road to Hastings Street when the great shock struck. He felt the back of the car rise and wobble, then saw the road rear up and burst. The ground struck his car underneath. There was a roar and a crash of masonry, buildings toppled like cards, and shouts and screams of terrified people. For safety he tried to drive in the middle of the road, but the vertical movement threw the car over to the left, fortunately against a lamp-post, otherwise it would have toppled over. Turning around behind him he saw a wooden shed rolling down like a ball from Shakespeare Road.

People were running into the streets, many to be buried in debris, others sheltered in doorways. It was noticeable that more women rushed in to the streets than men, more of the latter preferring to remain under shelter. Parked taxis and cars were flattened like sixpences. A pall of dust rose over the town, and a column of smoke and flame shot up from the Masonic Hotel, followed by others in the business area around.

Next dawned beautifully fine, but with the wind blowing briskly. There was a sickening smell abroad, of things burnt and burning, leaving no desire to eat, only for something to drink. Water and tea were to be had, and people with artesian wells had written signs of “Water here – help yourself.”

BOMBARDED BY BRICKS.

PROVIDENCE saved them – nine helpless babes out in their bassinets in the yard of the Bethany Home of the Salvation Army in Fitzroy Road Napier. Bricks hurling from topping chimneys on three sides of them filled their bassinets, but the babes were found unscathed and not even particularly frightened. At the moonlit hour of 2 a.m. next day, sound asleep they were lifted into a big service bus and brought into haven in Wellington by Captain Delaney, Lieutenant Durie and Miss Thompson.

A special dispensation was surely theirs, for their immediate necessities were in no way disturbed. Out of the confused wreckage of the Home’s crockery littering the kitchen floor, their feeding bottles, which had been standing on a shelf, were picked up unbroken. In the yard, their Plunket food which had been made just before the quake and put there to cool, did not even have the covering gauze displaced.

THE FIRST NIGHT.

The hours of darkness which followed the horrors of the day yielded rest to few. In the country and town the “New Zealand Free Lance” wandered amongst hundreds of people turning feverishly on outdoor pallets. Groups of neighbours sheltered under canvas, rugs and sheets in some favoured garden. The beach along Marine Parade was the biggest communal camp. But others were organised in the parks.

The night was punctuated with the concussion of earthquake, and explosions amidst the tumbling inferno of the business areas. At some particularly heavy shock terror-stricken faces would look in vain for outside help, but in Napier all the people could see on the horizon were the flames of Hastings.

Every now and then, especially as dawn drew on, people arose restlessly and wandered amongst the refugees looking for loved ones, or pressed forward once again on a helpless contemplation of ruins beneath which the remains of those they sought possibly lay. Yet with all this strain and sorrow there was also a wonderful restraint.

RESCUE AND RELIEF.

BRILLIANT individual rescues during the first few moments when the bottom fell out of Hawke’s Bay’s ordinary life were followed by a shocked lull.

The authoritative work of relief and organisation came from the naval sloop Veronica, whose name will go down in the history as a ship which did more than its duty in the crisis. Aided also by the masters of the Northumberland and Taranaki, Commander H. L. Morgan, D.S.O., gave to the outside world the first details of the shake, received homeless people upon its decks, and landed the first forces. While H.M.S. Dunedin and Diomede, bigger ships, with bigger crews, were rushing from Auckland, making bread and splints as they came, he took the first step towards comprehensive organisation by collaborating with the police. By the time the Wellington night duty constables – with pyjamas beneath their uniforms – arrived at breakneck speed to reinforce their fellows in Hawke’s Bay, the Navy had already started rescue, medical, water and food supply and patrol services. With the arrival of the other naval vessels, this organisation was developed.

In rescue work the naval men maintained the highest traditions of their calling, and none appreciated their efforts more than that tough band of Napier navvies and council employees whose brown, bare shoulders toiled till Nature’s demands for rest seemed to have been permanently denied.

Several of these navvies as they hauled masonry off the dead and one or two still alive, commented on contractors who built the unstable buildings which flaked off like cheese at the slightest strain.

“I built this cornice,” said a lad of 18 with a man’s maturity to the reporter, “and I laughed at the quality as I built it. To think today I’m pulling the same material off people crushed!”

AIR TRAGEDY.

A PARTICULARLY sad occurrence associated with the earthquake was an aeroplane accident at Wairoa whereby three relief workers lost their lives. They were Flight Lieutenant I. L. Kight, barrister, of Dannevirke; Mr. Walter Findlay, baker and confectioner of Gisborne; and Mr. W. C. Strand, of A. S. Paterson and Co., son of the ex-Mayor of Lower Hutt. The machine was a Dominion Airlines monoplane. It left Gisborne with mail matter for Wairoa, and, having dropped it, rose to proceed. The motor, however, stalled, and the ’plane dived into the side of a road. Two of the victims were killed outright, and one died in a few minutes.

[Advertisement]

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 7

Rather than risk the perils of their own roof, many families accommodated themselves on the beach at Napier with rugs, mattresses and a few household belongings. – A.W. Schaef.

Very few Napier folk slept indoors during the days following the disaster. Fortunately the weather was fine. – A.W. Schaef.

SEEKING SAFETY: FAMILIES, CAMP ON MARINE PARADE.

8 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

VALUABLE ASSISTANCE RENDERED BY NAVY.

Fortunately, at the time of the earthquake, H.M.S. Veronica was at Napier, and immediately took charge of the situation. The following day H.M.S. Dunedin and H.M.S. Diomede arrived from Auckland with doctors, nurses, and medical stores. Sailors and marines were promptly landed, and in both Napier and Hastings did excellent rescue work. Top: Bluejackets searching amongst the wreckage in Heretaunga Street, Hastings. Centre: A signaller from H.M.S. Veronica receiving instructions from the vessel shortly after the earthquake. Below: Commander V. A. C. Crutchley, V.C., D.S.C., of H.M.S. Diomede, supervising the clearance of overhead wires in one of the streets. – A. W. Schaef (2) and E. T. Robson.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 9

Devastated Hearths and Homes.

How Hawke’s Bay People Fared.

REFUGEES from the devastated district poured into Wellington last week, each with a tale to tell of narrow escapes and desperate desolation and ruin. They arrived by cars and trains at all hours of the day and night, dazed by the shock. Some of the escapees have only a hazy recollection of what happened after the first awful shake.

Mr. and Mrs. F. N. Fussell arrived from Napier last Wednesday with their few earthly possessions wrapped in a flag. They saved nothing, as the fire started in their house immediately after the shake, and their house and their car were reduced to ashes in a few moments. They are staying with Mrs. Graham Robertson.

Many people camped with friends on the hills by night as a tidal wave was feared. Dr. and Mrs. Bernau are safe, but their home in Thompson Road was destroyed. Most of the houses on the hills have chimneys down, twisted walls and jammed doors. On Dr. and Mrs. Harvey’s home the whole cliff crashed, and it fell like a pack of cards but they escaped unhurt. The Misses Joan and Marjorie Campbell, and their father, Mr. A. Campbell, reached Wellington on Wednesday and are now the guests of Col. George Campbell. Mr. F. Hetley and his wife and daughter have also arrived in Wellington.

Mrs. Chris McLean’s daughter, Dorothy, is reported missing and so is Miss Madge Newton. Mrs. A. Campbell remained on in Napier with Mrs. Newton.

Mrs. St. John Hindmarsh, the young wife of Councillor Hindmarsh, is among the dead. She had gone from her beautiful home in Lincoln Road into the town to have her hair cut when the earthquake began. Her husband searched the smoking ruins of the hairdressing parlour all night in vain, with gathering despair. At length her body was discovered. What makes the tragedy still more poignant is that the attendant who was attending to her managed – by some miracle – to escape. The Hindmarsh house is badly twisted and every chimney down, and the little daughter of the house had her arm broken.

Mrs. Pasley, who is over seventy, and her elder daughter, Ethel, had their house severely shaken and twisted, but escaped unhurt. Miss Helen Pasley was not at home at the time. Mrs. Pasley and Miss Ethel arrived in Wellington on Thursday evening to stay with Mr. Phil Pasley and his family in Fitzherbert Terrace.

Dr. Arthur Clark’s house in Clive Square, which formerly belonged to Dr. Graham Robertson, escaped fire and serious injury. His young wife has gone to stay with her mother, Mrs. London. Dr. Clark has been working night and day in the improvised hospital. Mrs. Dudley Kettle and her mother, Mrs. E. J. Riddiford, have been motored back to Wellington by Mr. Eric Riddiford, who also brought back Miss Enitha Bunny who was staying with her aunt Mrs. Riddiford, on the Bluff Hill. This little party camped all night in Mrs Cox’s garden, with the earth trembling violently under them and Napier blazing below. A terrible night which will never be blotted from their memories.

Mrs Bower-Knight has offered her large home in Dannevirke to the various members the Hindmarsh families whose homes have been wrecked in Napier. She and her family have taken a cottage in Seatoun. Mr. Hindmarsh’s motherless children will stay there.

Mrs W.J. Geddis and her son and daughter-in-law (Mr. and Mrs. Clifton Geddis) who lived together on Bluff Hill fortunately escaped personal injury, but their beautiful home was badly damaged and they spent night camped out on their lawn, remaining there until they were to get away to Palmerston North.

Mr and Mrs Trevor Geddis and their two small children also living on Bluff Hill similarly lost their home and were glad to escape with their lives. Mr. Trevor Geddis ls the managing director of the Napier “Daily Telegraph” newspaper, the building of which nothing remains but a heap of shattered heap of shattered masonry.

Mrs Macrae’s house in Clive Square is badly injured and she has come to Wellington, where she is staying at Island Bay with her sister, Mrs Kean. Mrs. Pat McLean’s house on Thompson Road was badly twisted but the dear old couple who are much loved and respected in Napier are badly shaken but otherwise unhurt.

A little romance centres round Miss Joan Wright, of Wellington, who was in Napier on the fatal day, staying with her aunt, Mrs Harold Douglas, whose home in Elizabeth Road on Bluff Hill was wrecked. Her finance, Mr R.E. Pope, dashed by car from Wellington on the first news of the ‘quake and their engagement was announced last Friday, after he had brought her safely home to her parents, Mr and Mrs. G.W. Wright. Mr Pope is a partner in the legal firm of Perry, Perry and Pope.

To illustrate the force of the shake, an inmate of Mrs. Harold Douglas’s house who was standing at the front door was shot fifty feet on to a sloping lawn, and the next upheaval threw her over a wall onto the road beneath.

Mrs. Howard Coleman had a luck escape: she had motored into Napier, to shop. The building began to oscillate violently and bricks fell, but she was able to creep out from the ruins and regain her car.

Mrs. Shailer Weston’ s friends were very anxious about her as they believed her to be in Napier. But on Friday morning a wire arrived to tell that she was safe with her sister, Mrs. Reggie Ludbrook, whose station lies about 100 miles north of Gisborne. Mrs. Weston – luckily for her – left Napier on Monday and motored herself north, just escaping the ’quake which destroyed the Napier-Wairoa road.

The two daughters of Mr. A. Thorne George, manager of the New Zealand Insurance in Napier were both nurses at the Napier Hospital. Both were on night duty, and in the terrible collapse of the Nurses’ Home. Nancy was killed, while Margot was injured and was one of the first cases sent to Palmerston North Hospital. Mr. and Mrs Thorne George are both safe, though the former was at first reported missing. Miss Gwen Hadfield, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Hadfield of Wellington, who is a nurse in the Napier Hospital, was on day duty and so fortunately, is uninjured.

The venerable Miss Kate Williams, of Hukarere Road who attended the last fatal service in St. John’s Cathedral, died of heart failure when the crash came which also killed Mrs. T. Barry senior and injured Archdeacon Brocklehurst.

Mr. and Mrs. Ned Smith’s magnificent home, which had just been finished, is completely destroyed, but his wife, who is a daughter of the late Dean Mayne, and her family escaped uninjured.

Mr. and Mrs. Charles Miles, who motored to Napier, were able to return with Mrs. Miles’s sister, Mrs. Edwards, and her mother, Mrs. Craig. Mrs. Craig was upstairs in the bedroom of her house on the Marine Parade when the ‘quake began. She was just able to escape – inadequately clad and very shaken but otherwise uninjured. Mr. Craig was just getting the car out of the garage and fortunately was able to get away before a theatre at the back crashed on to the garage and the car.

Photo caption – WEDDED MIDST DEVASTATION. Miss Molly Donnelly, whose wedding to Mr. Jack Chambers took place in the garden of her seriously damaged home at Hastings at 5 p.m. on earthquake Tuesday. St. Luke’s, Havelock North, was being decorated for the ceremony when wrecked by the shake.

[Advertisement]

10 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

The roads into the earthquake zone suffered comparatively slight damage. – A.W. Schaef.

Owing to the failure of the Napier mains, water had to be transported to the towns in any available receptacle. – E. T. Robson.

Track and rails parted company at a small bridge outside Napier, and at various other spots, but as on the road the damage was not serious. – A.W. Schaef.

SURPRISINGLY LITTLE DAMAGE TO ROADS AND RAILWAY.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 21

The Nurses’ Home (left) and some of the wards at the Public Hospital before the earthquake. – G. Shaw.

Wreckage at the Nurses’ Home, where several night nurses lost their lives. – E.F. Morrell.

Huge blocks of masonry in the gardens of the Nurses’ Home. – A.W. Schaef.

Dr. Moore’s Private Hospital on the Parade showing the dangerous angle at which it is standing. – B. Hobday.

DESTRUCTION TO NAPIER HOSPITALS AND NURSES’ HOME.

22 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

A white inferno. Fire raging through shattered buildings in Hastings. On the right are the remains of the five-story Grand Hotel building. – C.F. Newham.

The Carnegie Public Library in Hastings, now nothing but a heap of bricks. Many people lost their live when this building collapsed. – A.W. Schaef.

DEATH AND DESTRUCTION WALK HAND IN HAND.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 23

The new St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Napier, which was almost completed, was badly damaged by the earthquake, and then the flames completed the work of destruction.

Two priests and seven students were killed when the chapel of the Marist Fathers’ Seminary at Greenmeadows, near Napier, collapsed. Five of the seven students were Old Boys of St. Bede’s College, Christchurch. Top: A statue of the Virgin Mary, patroness of the Seminary, which, although it fell a considerable distance to the ground, was undamaged. Below: The wrecked chapel, looking from the entrance porch to the High Altar. On the left are the remains of the pipe organ. – J. R. O’Shaughnessy.

CHURCH PROPERTIES DESTROYED: SERIOUS LOSS OF LIFE.

24 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

A tangled mass of fallen verandahs, with the clock still in position.

Private residences, the front wall of which collapsed into the road.

Volunteer workers and a tractor clearing wreckage from the Cosy Theatre.

Business premises in a precarious position.

The Assembly Hall, which suffered extensive damage. – A.W. Schaef.

HERETAUNGA STREET, MAIN THOROUGHFARE OF HASTINGS, DESTROYED.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 25

THE PRIDE OF NAPIER DESTROYED BY ’QUAKE AND FIRE.

Above: St. John’s Anglican Cathedral, a beautiful brick building and one of the architectural treasures of Napier. Below: The Cathedral as it appears today. The building immediately crumpled into ruins, trapping several of the congregation at a communion service. What was not destroyed by the earthquake was destroyed by the fire which swept through the building, incinerating Mrs.T. Barry. The War Memorial Cross in the Cathedral grounds remained intact, although every other memorial in the town was shattered or uprooted. – S. C. Smith and Crown Studios.

28 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

Carpenters at work in the grounds of the Nurses’ Home, Napier. – E.T. Robson.

The old Post Office building at Napier damaged by the earthquake and then completely destroyed by fire. Note the three strong-rooms. On the left centre may be seen the War Memorial Cross which still stands intact in front of the ruins of the Napier Cathedral. – Crown Studios.

NAPIER – CITY OF DEATH AND RUIN.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 29

The new Post Office at Napier, opened a few months ago, practically withstood the earthquake, but was completely destroyed by fire. Many lives were saved in the shelter of the building.

The new Post Office at Hastings, which was badly damaged by the ‘quake. – Crown Studios.

NEWLY CONSTRUCTED POST OFFICES SHATTERED AND BURNT.

30 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

WHERE DEVASTION WAS GREATEST AT NAPIER.

The residential areas of Napier were not affected to the same extent as the business portion of the town, though fallen chimneys and burst waterpipes and cisterns wrought havoc in hundreds of homes. The smoking ruins of the business area are seen in the right foreground.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 31

The ruins of prominent business houses in Emerson Street, one of Napier’s business centres. Here serious loss of life occurred. The work of clearing away the debris is now well in hand. – E. Hobday.

A grim task. Men searching among the debris in Heretaunga Street Hastings, for victims of the disaster. – C.F. Newham.

REPAIR GANGS DOING GOOD WORK.

32 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

ALONG THE WHARVES: THE NAVY’S PROMPTITUDE.

Above: The floor of the Inner Harbour at Napier was permanently raised several feet and bumped the keel of H.M.S Veronica (Captain H.C. Morgan). But the promptitude in landing parties and organising the situation was an admirable feature of post-‘quake operations. Below: The railway line along the Inner Harbour waterfront was left twisted and useless.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 33

THEIR ONLY HOMES: REFUGEES RESTING IN THE OPEN.

As soon as the earthquake had subsided, residents collected a few necessities from what remained of their homes and camped on the open spaces about the town.

Top: Families with babies camped on the beach, their dogs huddling beside them. Centre: Residents collecting their ration of water after the mains broke.

Below: Weary refugees improvised beds in one of the reserves. – Crown Studios.

34 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

Forcing open the safe of the Bank of New Zealand at Napier. It was necessary to wait a few days before the safes became cool enough to handle. Note the armed marines on guard. – E.F. Morrell.

The large marble statue of soldier with reversed arms surmounting the South African War memorial at Napier was thrown to the ground, the fall breaking the head from the body. In the background is the Y.M.C.A. – E.F. Morrell.

AFTER THE TURMOIL: BANKS GET BACK TO BUSINESS.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 43

The band rotunda near Masonic Hotel, Marine Parade, Napier, as it was after the earthquake. – A.W. Schaef.

In Hastings Street, Napier, a valuable motorcar was reduced to junk by the toppling of a brick wall. – E.F. Morrell.

THE IRRESISTIBLE FORCE: TWO CONTRASTS IN BUILDINGS.

44 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

“No Road”. Members of the special police who were on duty at all intersections in the devastated business area in Hastings. – E. F. Morrell.

One of many motor-cars which were crushed in Heretaunga Street, Hastings. – C. F. Newham.

Volunteer labourers clearing up the main street in Hastings. – C. F. Newham.

SALVAGE AND REORGANISATION WORK IN HASTINGS.

46 NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. February 11, 1931.

“NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE.”

THE NATIONAL PICTORIAL WEEKLY.

Founded – – July, 1900.

PUBLISHED WEEKLY.

TERMS 0F SUBSCRIPTION.

(In Advance):

Twelve Months (including Christmas Annual) 35/-

Per Quarter (In Advance) 10/-

Per Quarter (Booked) 11/-

Posted free regularly to any address in New Zealand. Outside New Zealand extra postage added.

LONDON OFFICE. – R. B. Brett and Son, New Bridge Street House, 30- 34 New Bridge Street, London, E.C.4.

SYDNEY OFFICE. – W. J. Heslehurst, Commonwealth Bank Chambers, 32 Castlereagh Street.

MELBOURNE. – The “NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE” is obtainable at railway bookstalls or from Gordon and Gotch (Aus.), Ltd., Queen Street.

Money orders, cheques, etc., and all business communications should be addressed to –

Proprietors of “NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE,” 31, Panama Street, Wellington.

Here shall the Press the people’s right maintain,

Unawed by influence and unbribed by gain;

Here patriot Truth her glorious precepts draw,

Pledged to Religion Liberty and Law.

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 1931.

Scinde Island: The Site of Napier.

A Waste that Became a Beautiful Town.

BY JAMES COWAN.

(FOR THE NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE.)

LOOKING out from the hill-top garden-land that dominates the level town site of half-demolished Napier, one is impressed by the sharp contrast in the configuration of this seaward face of Hawke’s Bay. The highland that is generally called the Bluff Hill and that stretches away in tree-shaded ups and downs to the bold Hukarere Cliffs overlooking the Breakwater and Port Ahuriri, was an island not so long ago, and the sandy plain over which the town spreads for miles was under water. It is probably only a very few centuries since the waves of the Pacific rolled over all this vast flat land for many miles inland. The unwatering of all this Heretaunga marsh and plain was gradual; the recent earthquake has given it a sudden quick kick upward, judging from the reported shoaling of the port.

But if the land is making, the general strong impression remains, that the high places on which the residents have built their homes – at any rate, the older homes of Napier – are a kind of islanded retreat from the lowlands of business and industry, and a place of refuge from ocean invasion should the old gods of the Pacific ever take it into their heads to sweep over the reclaimed shallows again. Like a many-coloured table surface, the vast plain sweeps away to the south, its ocean limit defined by the white band of surf stretching in half-moon shape to yon far-off cliffs of Cape Kidnappers. Hot and monotonous it looks, the plain shimmering in the heat-waves.

But up here on the green hill, all cut up into softly-foliaged and flower-adorned valley and slope, and here and there a few level acres, it is another world. No dust, abundance of shade, gardens everywhere, pretty homes sequestered amongst their roses and their orchards, and grand old trees, some of them the growth of seventy years and many dwellings of early colonial type, built of the best timbers. These wooden buildings, by the way, often withstand seismic shocks better than the most modern materials, certainly better than brick, which it is tragically obvious now should never be used again in areas liable to earthquakes. Here, surely, is a lesson by which Wellington City should profit.

Scinde Island, the name given by Alfred Domett when he was Commissioner of Crown Lands and laid out the town of Napier in the late Fifties takes in a portion of the flat land that was a waste of shingle and pumice-sand eighty years ago, when the site of Napier was acquired from the Maoris – little value indeed they set on it then. But this highland may be considered the island proper, so completely an island does it appear from a distance. When one comes to climb it and rove about its leafy roads and in and out of its little glens, its area seems considerably larger than a first view would lead one to expect. It is the great charm of a visit to Napier – or it was before last week’s tragedy – to wander about those highways and byways on the Hill, where every turn showed a new picture of semi-rural beauty, and every vista of far-off ranges and broad plain and ocean gave one a sense of being high above the hot and scurrying world.

As pleasant a hill-top way as any, where one might admire many a cosily-placed, often handsome, home, was the Hospital Road – alas, a name of sorrowful import today. Here, too, one saw one of the best-built and best-equipped Government primary schools in the Dominion – it is next door to the great old groves and the wide lawns of Lady Maclean’s historic dwelling. Probably there is no school in New Zealand that enjoys so healthy and airy a location. Not far away is another, but older, school, the Hukarere College for Maori girls, an excellent institution, where the Church of England teachers have educated many hundreds of girls, including some from far-away Rarotonga and other South Sea islands of ours.

Passing the garden-like Cemetery and the Botanical Gardens, all slanting gently to the south, with an outlook for fifty miles over the plains, there is the Hospital, or what remains of it, with its story of blended horror and heroism.

FATAL HUKARERE BLUFF.

By up and down ways one reaches the boldest buttress of Scinde Island, the seaward bluff of vertical rock, where some too-venturesome house-builders had perched themselves on the very verge of the cliff. That was the lip of the Hukarere bluff that collapsed in an avalanche sickening to think of, on the very first impact of the earthquake. Hukarere – it means “Flying Foam” – by the way, must have been an exceedingly appropriate name in the pre-Pakeha days, before roads and breakwaters were made, when the waves of the Pacific beat against the very foot of the cliff and in gales sent sheets of spray high up the great rock face.

In more sequestered parts of the long island-hill, there are the homes of some notable New Zealanders. One old resident, whose garden is quite a floral museum, is the veteran Henry Hill, retired Chief Inspector of Hawke’s Bay Schools. Mr Hill is not only a botanist, but a geologist, and he is particularly an authority on the volcanic regions of the interior. He was exploring the Taupo-Tongariro country more than half-a-century ago, and though his years are more than eighty, he’s keen as ever on the scent of new discoveries and happenings in the world of volcanology. The present disaster to his beloved Napier must be an inexpressibly saddening thing to him.

Another pleasantly-set home that comes to mind, among many bowers of flowers and shade, is that of Mrs. Kettle, daughter of the famous soldier-of-fortune Von Tempsky, who fell in bush battle in Taranaki more than sixty years ago. A family with an uncommonly interesting history, and with some gifted members. The brilliant young novelist Irma von Tempsky, of Hawaii – she has shortened the name to Irma Tempski for her books – who wrote “Hula,” “Dust,” and other stories, is Mrs. Kettle’s niece.

The Earthquake Disaster.

HAWKE’S BAY shimmering in the Summer sun, attuned to the peaceful commerce of fruit and wool. Then, like the crack of doom, the blow fell! The prosperous cities of a smiling countryside were cast suddenly into ruins and under a pall of dust, smoke and flame hundreds of men, women and little children met violent death or serious injury.

So sudden, so tragic, so immense an upheaval those who went through it are unable to describe. In the towns of Napier and Hastings it was the business part of the morning: Folk hustled through the streets, offices hummed with activity, shops assiduously attended the necessities of customers, in the hospitals patients lay on the operating tables, in a church the communion service was being held. Into these ordinary avocations the most powerful forces of Nature were impelled with a bang and a heave and the crashing of buildings.

When the first shock had passed the ties of citizenship and humanity quickly manifested their strength. There was no panic. The citizens rallied admirably and as far as human effort could oppose the elemental forces everything possible was done to help the less fortunate. It was an inspiring thought – the deeds of daring, the lives risked and lost for others, as, for instance, at the Napier Hospital. And to the Navy’s assistance, so promptly and so effectively exercised by H.M.S Veronica and later H.M.S. Diomede and Dunedin, folk of the earthquake area owe special gratitude. Indeed, the manner in which the people bore up and organised under their bereavements and injuries and the uncertainty as to the possibility of another shake is a tribute to the qualities of the race.

No accurate estimate of loss of life or of the damage to property can yet be made. Among their ruins Napier and Hastings still count their casualties. The pictures and reports in this issue give, as far as pen and camera can, an idea of the seriousness of the cataclysm. After the vagueness arising from the telegraphic isolation of the scene, news soon roused the nation to help. Medical and nursing services rose nobly to the occasion, volunteer helpers organised in every direction, and the relief funds at once opened were promptly and liberally supported. Added to the fine spirit generally shown by our people the Dominion is sustained by heartening messages and help from overseas. Headed by the sincere condolence of Their Majesties the King and Queen came a list too numerous to particularise.

Millions may be needed to replace the damage done in Hawke’s Bay. The question has been raised: Should the monetary help proffered by other countries be declined. Why dam up or restrict the fountains of relief? There is a radical difference between appealing for aid to outside countries and out of a feeling of false pride turning down the offers of assistance that are spontaneously made from humane and generous feeling. Let us remember that “one touch of nature makes the whole world kin.” The opinion expressed by the Hon Mr Ransom that the situation should be dealt with as a national responsibility will be very widely shared throughout New Zealand. And the Christchurch City Council by its donation of £10,000 sets a fine example to the local bodies.

One other lesson. Must we confess ourselves an earthquake country? Perhaps not, but at least, let us face that possible issue. It can be done. The secret is more sensible – not more expensive – building. More sensible building in light of the Hawke’s Bay disaster means wood in the average residence; steel frame and ferro-concrete in business. The triumph of the tree at Napier has been complete. Judging by the comments in that stricken centre, brick, stone and composition are materials of the past. In the study of earthquakes themselves, of building and many civil engineering problems from an earthquake standpoint, science will do New Zealand a very practical service.

Hawke’s Bay has well earned its reputation as the garden province. At this time of year its orchards groan beneath loads of luscious fruit and on its pastures graze nearly five million sheep. This prosperity is not over. The Province will in good time recover its stride like San Francisco after its destruction. Napier and Hastings will rise from the ashes. The Province needs and will surely receive the practical sympathy and support of all.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 47

A panoramic view of Napier, showing the principal buildings which were destroyed in the earthquake. On the left, with the verandah poles, is the Masonic Hotel. On the right is the Anglican Cathedral, and to the right again, with the pillars, the Public Trust Office, one of the few buildings remaining standing. Above the Public Trust is the Technical College.

A comprehensive view of the Marine Parade, showing the fine stretch of beach. On the right is the Bluff Hill, where a serious slip occurred. Hastings Street, the main business and shopping centre, can be seen on the right, running parallel to the Parade.

A busy scene at the Inner Harbour wharves at Napier before the ’quake. – S.C. Smith.

BEFORE THE UPHEAVAL: NAPIER AND ITS WHARVES.

February 11, 1931. NEW ZEALAND FREE LANCE. 49

Several men were killed by falling bales when the New Zealand Shipping Co.’s wool store collapsed at Port Ahuriri. – C. F. Newham.

Looking up Tennyson Street, Napier, from the Parade. In the background on the left, is the Public Trust Office, one of few two-story buildings still standing. – B. Hobday.

IN THE PATH OF DESTRUCTION : NAPIER AND PORT AHURIRI.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Description

Surnames in this newspaper supplement –

Anisy, Barry, Bernau, Biggs, Bower-Knight, Boyle, Bunny, Campbell, Carmody, Chambers, Clark, Coleman, Cowan, Cox, Craig, Crutchley, Delaney, Devonport, Domett, Donnelly, Doogan, Douglas, Durie, Edwards, Findlay, Fussell, Geddis, Geddis, George, Gondringer, Hadfield, Hill, Hindmarsh, Hobday, Kean, Kettle, Kight, London, Ludbrook, Maclean, Macrae, Mangos, McLean, Miles, Moore, Morgan, Morrell, Newham, O’Shaughnessy, Pasley, Pope, Rafter, Ransom, Riddiford, Robertson, Robson, Schaef, Shaw, Short, Smith, Stevenson, Strand, Tempski, Thompson, Thorpe, Von Tempsky, Weston, Williams, Wright

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.