- Home

- Collections

- BREWARD J

- Our Welsh Grandparents

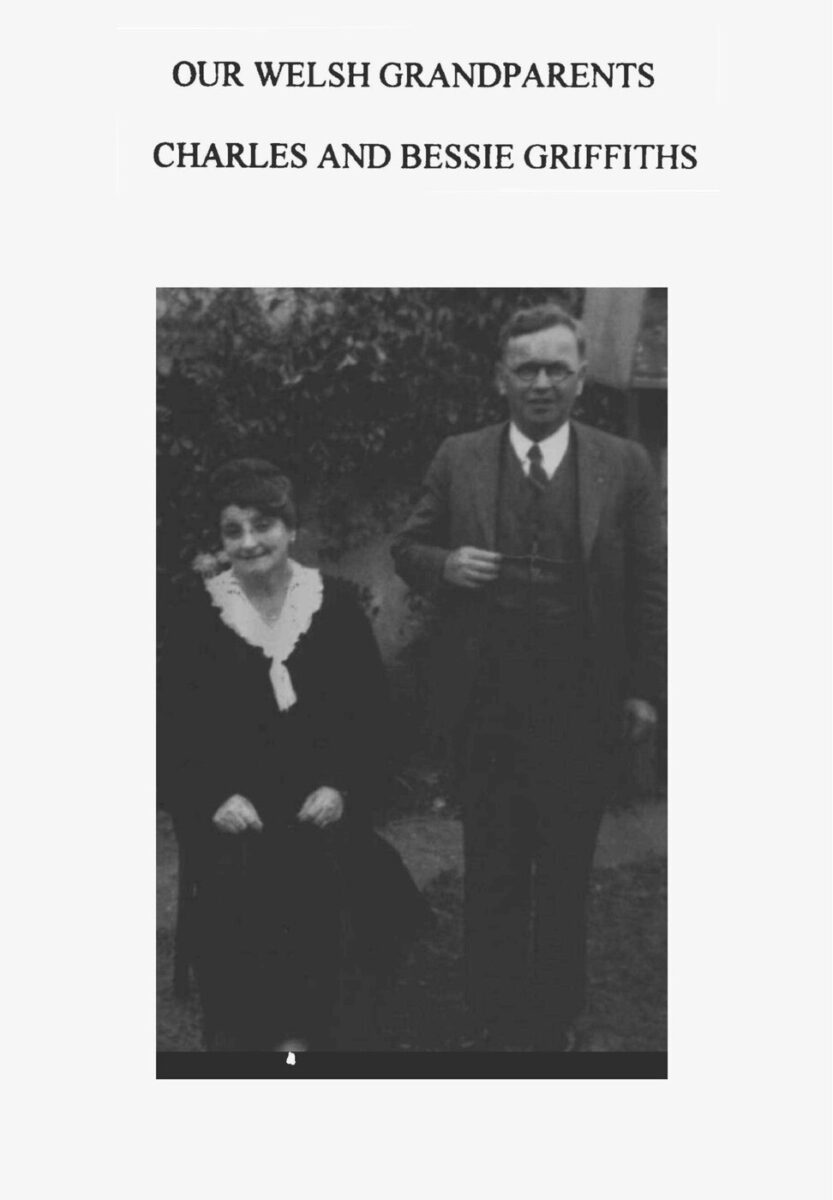

Our Welsh Grandparents

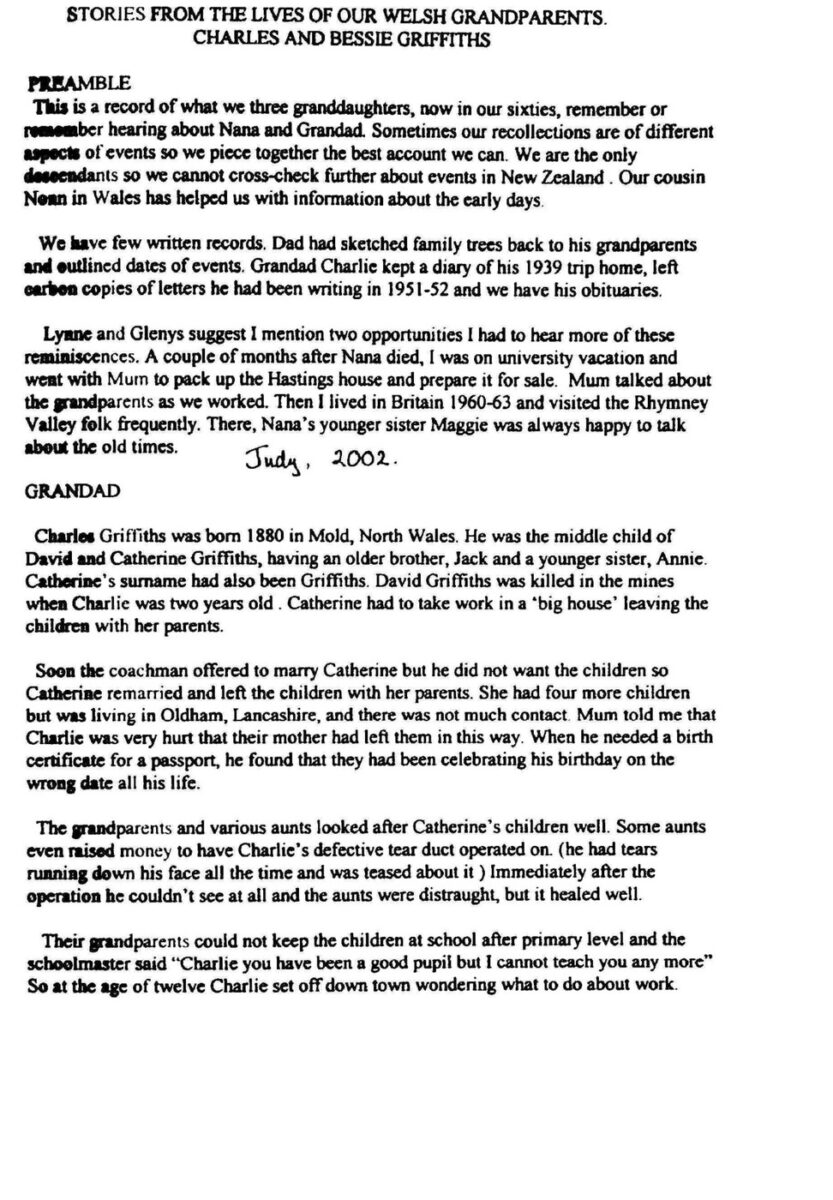

STORIES FROM THE LIVES OF OUR WELSH GRANDPARENTS.

CHARLES AND BESSIE GRIFFITHS

PREAMBLE

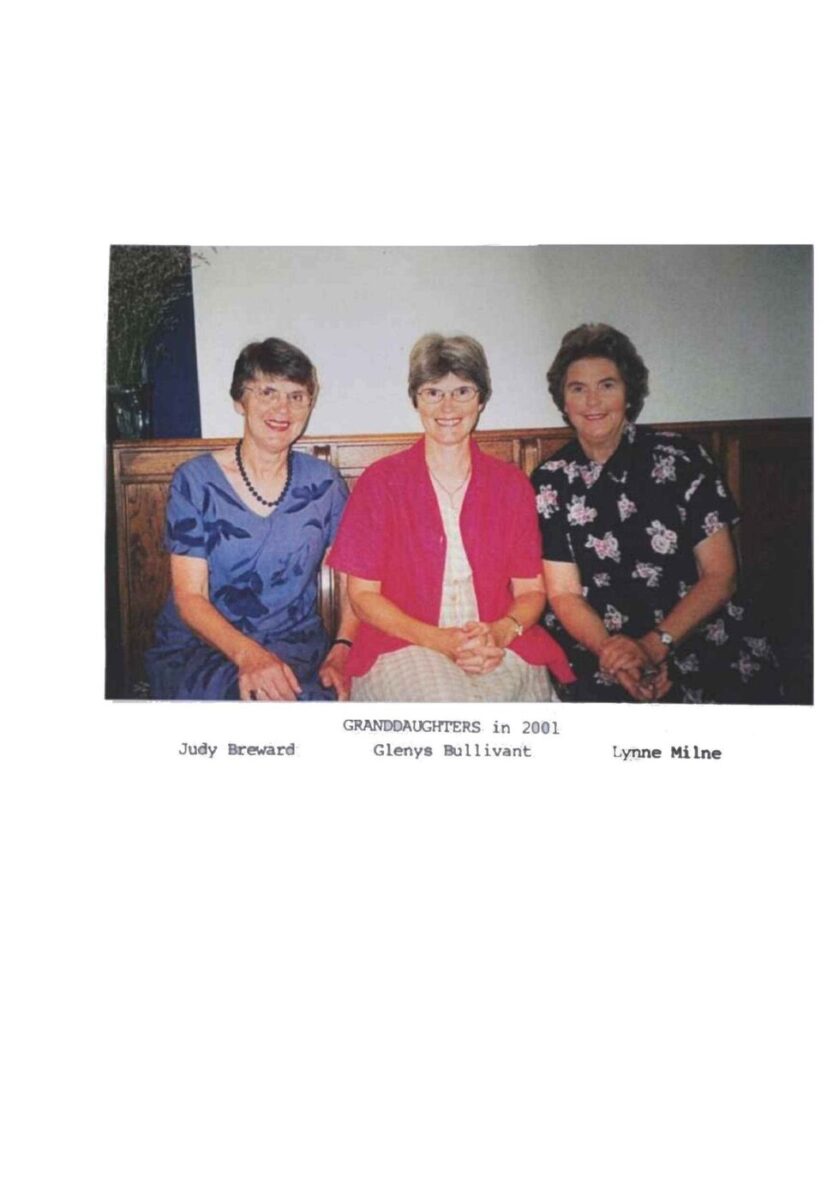

This is a record of what we three granddaughters, now in our sixties, remember or remember hearing about Nana and Grandad. Sometimes our recollections are of different aspects of events so we piece together the best account we can. We are the only descendants so we cannot cross-check further about events in New Zealand. Our cousin Nonn in Wales has helped us with information about the early days.

We have few written records. Dad had sketched family trees back to his grandparents and outlined dates of events. Grandad Charlie kept a diary of his 1939 trip home, left carbon copies of letters he had been writing in 1951-52 and we have his obituaries.

Lynne and Glenys suggest I mention two opportunities I had to hear more of these reminiscences. A couple of months after Nana died, I was on university vacation and went with Mum to pack up the Hastings house and prepare it for sale. Mum talked about the grandparents as we worked. Then I lived in Britain 1960-63 and visited the Rhymney Valley folk frequently. There, Nana’s younger sister Maggie was always happy to talk about the old times.

Handwritten: Judy, 2002

GRANDAD

Charles Griffiths was born 1880 in Mold, North Wales. He was the middle child of David and Catherine Griffiths, having an older brother, Jack and a younger sister, Annie. Catherine’s surname had also been Griffiths. David Griffiths was killed in the mines when Charlie was two years old. Catherine had to take work in a ‘big house’ leaving the children with her parents.

Soon the coachman offered to marry Catherine but he did not want the children so Catherine remarried and left the children with her parents. She had four more children but was living in Oldham, Lancashire, and there was not much contact. Mum told me that Charlie was very hurt that their mother had left them in this way. When he needed a birth certificate for a passport, he found that they had been celebrating his birthday on the wrong date all his life.

The grandparents and various aunts looked after Catherine’s children well. Some aunts even raised money to have Charlie’s defective tear duct operated on. (he had tears running down his face all the time and was teased about it) Immediately after the operation he couldn’t see at all and the aunts were distraught, but it healed well.

Their grandparents could not keep the children at school after primary level and the schoolmaster said “Charlie you have been a good pupil but I cannot teach you any more” So at the age of twelve Charlie set off down town wondering what to do about work.

A man came out of the boot shop and said “Sonny, can you take this parcel to such and such an address? “Charlie, as Grandad, often related how he ran all the way there and back. The boot shop man was pleased and offered him work. Charlie’s career had been decided.

Charlie went to a formal boot-making apprenticeship in Rhyl in his late teens. He then moved several times and became a manager of boot stores.

HOW CHARLIE SAW QUEEN VICTORIA

This story was told me as happening in Crewe. Charlie was managing a shop there when Queen Victoria was to visit but the shop owner would not allow them to close the shop for any more than the minimum time of the royal drive. At last Charlie could close and he ran. The royal carriage was already approaching, he was a small man running along behind the crowds lining the route and quite unable to see over them.

Charlie came to a place where tiered seating had been set up for a large children’s choir to sing as the Queen passed. He broke through a barrier, there was an outcry, but he crawled under and right through, emerging in front of the children. The royal carriage was almost upon them. With great presence of mind, Charlie turned and conducted the children, looking over his shoulder to get a clear look at the Queen as she acknowledged the choir and their conductors. He then ran across the road and got lost in the crowd. His reverence for the old Queen showed as he told this story.

NANA, nee BESSIE DAVIES

By 1905, Charlie was manager of a boot store in New Tredegar in the Rhymney Valley, South Wales where Bessie Davies lived.

Our grandmother, Bessie Davies, born 1881, was the ninth child (one of thirteen) of Rees and Elizabeth Davies. Rees Davies was a mine engineer. Elizabeth, nee Evans, was the daughter of a well-to-do but unpopular agent for the owner of an iron mine. Glenys has a facsimile of this David Evans’ will. He owned four houses and a shop and some very good furniture. This furniture is still with the family in Penarth, Wales.

Elizabeth then, was well educated and saw to it that all her children were well educated. The family is proud of her friendship with the Welsh poet, Islwyn (her father had paid his debts.) There is a story that Elizabeth was so keen on public lectures that, in order to attend one, she once left all the children with their father’s brother, a David Davies. When she returned home, the house was empty! Uncle David had all the children down at the pub “even little Maggie wrapped in a shawl” and he was dancing on the tables as was his wont.

Young Bessie was a talented singer. Her father gave her singing lessons then sent her to practise with her brother Moses who accompanied her on the piano. They were both very

demanding of her efforts and Bessie seems to have found it pretty trying. She used to tell us how she once in exasperation told Moses “You are as bad as Father.” However she was very well trained and won prizes at the local Eisteddford [Eisteddfod].

When Bessie worked in Aberdare at the Tarian Press, she joined the Carradoch Choir there. The conductor, a Mr. Mabon, (later a noted M.P. for the miners) noticed that Bessie was good. He encouraged her and featured her as a soloist. However, when that choir went to sing in London, Bessie’s father could not go to chaperone her so Bessie was not allowed to join them.

The Davies sisters were good-looking young women and very conscious of their appearance. As Nana, Bessie told me how they used to moisten the dark red covers of their hymn books to get colour for their lips and cheeks. One of the sisters was talented at millinery and made them all large fashionable Edwardian hats which they then wore to Chapel. I’m sure they looked quite gorgeous. However after that Chapel service, the carriage from the manor house came to their house and the girls were told that they were “dressing above their station” and it was to stop!

Class distinctions were strong and conditions for those working in the mines were very hard. Bessie’s father, Rees Davies was the mine engineer who drove the wheel and cage which let the men deep into the mine. When Rees became secretary of the local miners’ union he was dismissed, but the next shift of miners refused to go down without him in control of their lives in the cage, so he had to be reinstated. Our Nana was always very proud of this.

Later, Nana’s sister Miriam’s husband, Tom Evans, became very prominent in the unions and the Labour Party but the many stories about him will have to belong elsewhere.

Charles Griffiths, new to the Rhymney Valley, heard Bessie sing and was immediately taken with her. He began to court her but Bessie had another suitor too. As Nana, she used to tell me how she left early for work so that she could travel up the valley on the train with one young man and back down with the other! Her father was very strict with his girls and Bessie always remembered how when one young man had given her a lovely china cup, she was so worried and hurried about getting home late that she fell and broke the cup.

Charlie was the successful suitor and he and Bessie were married in 1905. Their son, Rhys was born in October 1906. Bessie used to declare that she had “enough milk to feed a village”. Rhys was a much-loved and very beautiful little boy. His many aunts fussed over him with great delight. Photos were taken of him with his beautiful curls – even one where he wore only a lap-full of tulle. This, the grown Rhys found embarrassing.

MIGRATION

In 1909, Charlie decided that they could improve their opportunities in life and provide better chances for Rhys by emigrating to New Zealand. Bessie’s brother Davy was already there and he recommended that they bring their boot stock to Westport, a coal-mining centre where Davy lived.

Charlie had been living away from home for years but this was a huge step for our grandmother to leave her close and happy family. Bessie was very frightened at the prospect of leaving and of the voyage. Charlie later told our mother that he was very proud of Bessie for agreeing to come as all her family were fearful people. All the same Charlie had his work cut out.

This story about London could have occurred on their later trip but Charlie does not mention it in his very full diary of that departure. I always understood it was in 1909, and certainly in 1909 London already had deep electric underground trains and lifts. Bessie was frightened and upset at the prospect of traveling underground and would not go down. Finally Charlie said “You are all upset, there is a little room over here to be out of the way.” but the little room was a lift and down they went!

When they were to board the boat, Bessie became hysterical about this final and fateful step. After trying to calm and persuade her, Charlie picked up little Rhys and, as a last resort, walked up the gangplank with him signaling “If you want your little son, you’ll have to come” and of course she did. Charlie, as Grandad, also liked to tell us that at the compulsory brief health check, the ship’s doctor said “That’s a fine healthy little boy you have there.”

On the voyage, Bessie was initially very seasick and Rhys had to be minded by other women. At this stage, the little fellow spoke only Welsh so he had to be taught the English words for the toilet and so on.

During the voyage, there was a very bad storm. All the hatches and doors were battened down and they held a special church service. Nana often told us how she helped lead the singing of “For those in peril on the sea”

WESTPORT, NEW ZEALAND

On arrival they went straight to Westport but there Charlie found there was no market for his stock of boots because the feet of New Zealand coal-miners were much bigger than the feet of Welsh coal-miners for whom the boots had originally been made. Charlie had to take work on the wharves, loading and unloading the ships, and when he was able, he humped his boots round many remote mine settlements hoping to sell at least some. Life was hard and Bessie blamed Davy for giving them the wrong advice

Dr. Bathgate, once a GP in Westport writes how Charles Griffiths knew the miners’ love of music in that he found pianos in communities such as the Denniston Incline which were accessible only by foot or wooden rail coal trucks.

Bessie was soon asked to sing at functions especially women’s meetings. She took her beautiful little Rhys with her – dressed, she always told us, in tussore silk shirt – and he sang for them too. The best remembered was a typical Edwardian sad song “Play in Your Own Back Yard”.

Charlie had been much influenced by the Revival sweeping Wales in the early 1900s. Welsh Chapel was Calvinistic Methodist so initially they went to the Methodist Church in Westport. There, the minister announced that there would be a Euchre card evening in the church hall. This was an attempt to provide for the miners an alternative to the Pub but to Charlie, cards were gambling. He was shocked and left to join the Presbyterians. Rev. Thomas Miller of the Presbyterian Church later wrote what an inspiration Charles Griffiths was in encouraging them to pray about the very small Young Men’s Group. The result was that it grew considerably

HASTINGS

Early in 1914, they decided they must move and went to Hastings where a friend, Mr. Martindale had invited them. Charlie went ahead and Bessie and Rhys followed. In Westport, Bessie had had Davy’s wife Lizzie whom I remember as a gentle and sweet person. The move to Hastings was once again a matter of striking out on their own. At first they lived in Mr. Martindale’s orchard house and Charlie worked shovelling coal for the railways.

In 1915 Charles Griffiths and a Mr. lsaac Coffey set up a boot business in Heretaunga Street Hastings and bought a house in Hastings Street in which both families lived for a while. In 1916, Charlie bought Mr. Coffey out of both.

They worked hard at the shop. Bessie joined Charlie there while Rhys was at school. She did the office work and sold ladies’ shoes which was a new venture for the business. In 1952 Charlie wrote that she “by her keen business ability, soon won the admiration and confidence of the buying public and from that time till now, which is 44 years, we have continued to do better each year.” Bessie also took boarders to help with finances.

On Saturday mornings, Rhys had to go to the Moving Pictures which they considered safe while Bessie worked in the shop. From this dated his love of movies and good knowledge of early film stars.

Towards the end of World War 1 Charlie was called up but never sent overseas. He was in uniform when he caught influenza in the pandemic of 1918. He was not expected to live but did survive. This must have been a very anxious time for Bessie with the possibility of losing a loved husband and of being left alone so far from her family.

Dad Rhys told us of happy days in Hastings Street. The neighbour’s boys, Bob and Eardley Briggs and Georgie Bower were all much of an age and good playmates. Rhys’s father owned an empty section on the corner which was used as a dumping ground for the benzine tins used then. With these the boys built forts and towers and made a great din.

RHYS’S EDUCATION

However, the much mothered Rhys, their only child, seemed to be getting spoiled and his father decided to send him to boarding school. Rhys became a week-day boarder at Napier Boys High School, going home each weekend. The first year was very hard on him but he told us that his Welsh indignation came to his rescue in fights. Up till this stage, his mother had always bathed him, now he would not let her do so in case she would see the bruises on his body.

Rhys did well at school becoming Dux of the school and playing in the Rugby First XV as a second five-eighth since he was quite small. Rhys was also a keen tennis player. His father said that he would pay for Rhys to become a doctor or a teacher and Rhys chose to be a teacher.

In addition to the course at Wellington Teachers’ Training College, Rhys studied for a BA at Victoria University College. He also led the Junior Boys Bible Class at Kent Terrace Church. He was fulfilling all his parents’ hopes for him and they must have been very proud of him. I think this shows in a portrait taken when his mother visited him in Wellington.

MARY MCLEAN

At ‘Training Col’, Rhys met and fell in love with Mary McLean. He was quite young and this was a major crisis for his devoted and possessive mother who could not hide her distress. Mary was very grateful for the support and approval she received from Rhys’s father. There remained a good bond between them which is probably why Mary was able to pass on comments about Charlie’s youth.

Rhys’s father had been going to take him ‘home’ to Wales when he finished studying but Rhys chose to stay to plan and prepare for marriage. He was only twenty one when he got engaged but they did not marry till 1930, three and a half years later.

Rhys had to work out how to deal with the strong bond with his mother. After the engagement was announced, Mary’s relatives, Tom and Maggie Cook, gave a party for Mary and Rhys and their Wellington friends. As Rhys brought his mother from her hotel in a taxi, she became hysterical at the steep and twisty roads on Mt. Victoria. Rhys took her back to her hotel and stayed with her! Mary was hurt and embarrassed and said she would have to break the engagement. The difficulty was overcome but it was a major crisis for everyone

An attitude of resentment towards Mary as the woman who now became closer to Rhys than she was, continued for Bessie throughout her life. This envy was sometimes observable but not spoken about till we were adults. Mary felt accepted and supported by Rhys’s father and did not let the tension spoil our relationship with our Nana.

At the wedding, generous Charlie paid the caterers before Mary’s widowed mother could do so.

EARTHQUAKE

In February 1931, the Napier-Hastings earthquake was a major trauma. Bessie had just begun walking up town, as she always did, with cut lunches for the shop. She was thrown off her feet several times and suffered heavy bruising. Badly frightened, she went to her neighbour, Mrs. Briggs, and they did what they could to comfort each other. Both their houses were wooden and only the chimneys came down but china, ornaments and jars of jam and preserves were thrown from the shelves and broken.

At Griffiths Footwear, shoes in shelves right up to the ceiling came raining down, then large blocks of stone from the parapets of the Banks either side fell and came through the roof. Charlie was fortunate in that some of these fell in such a way as to create a space in which he was somewhat protected, but their office girl who had panicked at all the shoes falling, was killed as the stones fell. Charlie, of course, stayed till her body was recovered and they were sure there was nothing that could be done. It was an anxious wait for Nana and Mrs. Briggs. They could see there were fires in the town and they did not know if their husbands were safe.

There were many after-shocks but Hastings had sufficient water and artesian water and some sewerage so tents were issued to Hastings residents and they lived in those. With water mains extensively broken in Napier, fires there spread and most people in that city were evacuated.

Meantime Rhys and Mary were unable to find out if Nana and Grandad were alright. They borrowed a car from relatives of Mary’s and had to drive from Hamilton through Taranaki as all other roads were damaged and closed. It took them three days. Mum spoke of the ambulances and cars full of shocked people leaving Napier-Hastings as they approached. They were most relieved to find Rhys’s parents only rather bruised. They stayed to help at Hastings Street and slept in the tents too.

Sailors from the H.M.S. Veronica which had been in port at Napier were helping everywhere. They brought truck-loads of shoes from the ruins of the shop. These were stored in Grandad’s garage, hundreds of them to be sorted into pairs again. As soon as possible they began selling shoes from the garage. There had been some looting, so the occasional person asking for a shoe for a one-legged man was very suspect. Grandad was very amused that since these people were very particular about the style of shoe, he was

able to persuade some of them to bring the first shoe to match! He was then able to charge them for both shoes.

PROSPERITY

Griffiths Footwear thrived despite the depression and Grandad’s generosity to deprived families. For some years it had not been necessary for Bessie to work in the shop. They had their house, a wooden villa, altered and modernized with bay windows, a brick terrace and shuttered windows. The bathroom was remodelled to give them an inside toilet.

About this time, they were also able to help the family in Wales. As a miner’s union representative, Tom Evans was always docked pay for attendance at meetings. His wife, Miriam, had saved and saved until they could buy a horse and cart and do a milk round. Tom could then earn his living very early in the morning and still attend meetings. However, the horse died and that seemed to be the end of the road for them till Maggie telegrammed Griff in New Zealand and he immediately sent money for a new horse.

THE TRIP HOME TO WALES

In 1939, our Nana and Grandad went on their long planned visit back home to Wales, thirty years after leaving. Grandad kept a really good diary of the trip which should be read.

Their boat was the Orford ( which sounds like P&O). The Westermans, Hastings drapers, were also on board and they often shared a taxi at ports of call. Businessman that he was, Grandad recorded exchange rates, taxi fares and items like afternoon tea for five costing 3/4d.

They called at four Australian cities then Colombo, Aden, Suez, Port Said, Naples, Nice, and Gibraltar. Especially at the tropical ports, Grandad often records “Mam was very frightened and wanted to go back to the boat but I insisted …” Later in crowded London, he writes “I thought Mam would be scared but she acted bravely, at the same time hanging on to me in real earnest.”

Tom Evans met them at Southampton and in Wales they were very warmly received, asked to speak in Chapel and congratulated on their spoken Welsh. Tom Evans took time off work to drive them round. He and Griff became firm friends. However the Rhymney Valley folk later told us that Miriam and Bessie fell out when Miriam suggested that migration had been a soft option. Obviously Bessie‘s fur coat and cameo were luxuries which Miriam could never have but Bessie would be right to feel that Miriam did not know the pain of being separated from the family and so far from Wales, nor the culture shock of adjusting to New Zealand. Tom and Charlie helped their wives make it up before the trip was over.

Auntie Annie, Granddad’s sister, joined them on their Aberystwyth holiday. They were thrilled to go to the National Eisteddford [Eisteddfod] and especially impressed to visit London, the Houses of Parliament etc. They also went to Stratford-on-Avon and to Oxford.

A few weeks before the end of their stay, war was declared. They hurried back to South Wales and tried to get a boat-booking for New Zealand. The Westermans were in London and got a berth straight away, but Grandad and Nana had to stay with their booking on the Rangatiki for 16th September. They went down to London a day or so before, were given gas masks and experienced trying to get about in the blackout.

From Tilbury, they travelled in convoy, their passenger boat surrounded by merchantmen then battleships and destroyers. Grandad found it fascinating and gives a detailed account. They were escorted across the Atlantic but the main convoy went on to North American ports and they were not escorted in the Caribbean.

At Panama, Grandad managed to send a cable to Rhys saying they had reached the Pacific. In 1939, the Pacific was considered to be much safer but still no lights were allowed to show at night and they had sing-songs in the dark.

In New Zealand no shipping news was given out so as the time drew near, Dad would drive us regularly to places like Bastion Point to look up the Hauraki Gulf for ships. In the end, the boat came in at night. We all went to the wharf and I can remember Nana crying out to us in the crowded shed. I was then enveloped in her big fur coat hug. Lynne remembers the lovely presents they brought us, some embroidered with ‘A Present From Aberystwyth’.

GRANDAD GRIFF

In Church and Community.

Grandad Griff was a devout Christian. He kept some of the characteristics of his Welsh Revival experiences murmuring “Amen, amen to that.” as he listened to sermons. He was Sunday School Superintendent at St. Andrews Hastings for thirty years and was very interested in teaching methods. I can remember his enthusiastically showing his granddaughters flannel-graph figures on a green baise [baize] board, to tell a story. As an elder for 37 years he always strongly supported and befriended the minister. At the time of his death, he was Session Clerk and in his last Annual Report he wrote. “As members of Christ‘s church we are His declared witnesses. When we peruse this report we can decide whether our witness has been as faithful as it could have been.’’

Grandad was also an Assembly representative for twenty five years and well known there – several prominent churchmen later identified me as Charles Griffiths’ granddaughter saying, “She comes of good stock.” In that field he was very cautious about the early feelers for union with the Methodists but very keen and supportive of the New Life Movement of the late l940s and early 1950s.

Many framed texts were hung in Nana and Grandad’s house.

“As for me and my House, we will serve the Lord.” “Christ is the head of this house, the unseen guest at every meal, the silent listener to every conversation.” and “What doth the Lord require of thee but to do justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God.”

With Syd O’Neil able to manage the shop, Grandad became Chairman of the Presbyterian Social Service Association in the Hawkes Bay Region, and was enthusiastic for their projects. He was instrumental in establishing a new Children’s Home at Havelock North and he was very pleased at the improvement in their friend Annie Barker after he got her into a PSSA Home for the elderly.

He also served on the Hawkes Bay Hospital Board for many years and regularly went to the Hastings Hospital on Sunday afternoons to visit patients who had no other visitors. If we were staying, he liked to take a little granddaughter with him. He wrote, “patients know me and if they have any complaints or wish to get anything special, they tell me.”

Grandad was active in Rotary, Chamber of Commerce, Retailers Association, Patriotic Committees and a Member of the Licensing Committee. In community groups he was valued for his realistic common sense and sense of humour.

Grandad as a man

A three piece suit, particularly the waist coat, was a characteristic of Grandad’s appearance with his fob watch and its gold chain across his middle. He smoked a pipe which took quite a bit of lighting, Glenys remembers sitting on his knee watching the flame dip down and up and being allowed to blow the match out.

Grandad drove a large Morris with leather seats and wooden dash board. Classic car buffs tell us it sounds like the Morris Woolsey [Wolseley], – a car so large for a small man that people used to tease that he saw the road through, rather than over, the steering wheel. He tended to ride the clutch so that the engine roared.

A stock of little jokes, usually church based, kept us amused. “We know that they had Sunday School races in the Bible because it says ‘Moses came fo(u)rth’ ”. At Christmas, Nana used to put boiled sixpences in the Christmas pudding but Grandad would find shillings and half crowns in his helping! We were mystified till we discovered him, before the meal, scrubbing up a pocket-full of change.

His minister in an obituary said “It is probable that no man in Hastings had more friends or was more widely respected than Mr. Griffiths. This fine Christian gentleman with the loving heart and the helping hand has made a lasting place for himself in the memory of Hastings.”

NANA GRIFF

Although she was temperamental and full of fear, Nana had a great gift of warmth and capacity to make people feel special. She had her special taxi driver, special grocery assistant and so on and particularly her special grandchildren. This meant that when Nana’s neighbour, Mrs. Briggs, kept bantam hens, Nana obtained these small eggs especially for her grandchildren. They were dear little eggs, somehow better than other eggs, just for us.

Both Nana and Grandad gave much time and attention to their three granddaughters. They had no other family and we knew we were loved. Before we became too self conscious as children, we were encouraged to sing in public. Nana often asked us to sing when her friends came to visit or when she took us to their homes for traditional afternoon tea.

Good clothes were very important to Nana. She had a special dressmaker, Mrs. Flower, who made up the fabrics which Nana chose from Westermans in the style that Nana wanted. Before World War II she also sent beautiful little outfits for Lynne and Judy. (rationing affected this in the war). Our mother Mary graciously accepted these gifts realizing that Nana had never had a daughter to dress in pretty things. We also got shoes through the shop. Good quality English shoes like Kilties were provided and it was great fun to go and have our feet measured and new shoes fitted.

In the years that we remember her, Nana always wore a good dark dress with a bunch of lace at the V neck. The lace was liberally doused with lavender water and held in place by a lovely distinctive pale pink cameo. She regularly scrubbed this cameo to keep it clean.

Nana’s fearfulness, I remember particularly when she accompanied us on picnics. Whenever we went in for a swim or out for a row, Nana would stand by the car and cry after us, “Don’t girls, Don’t!” There was a much-remembered occasion when, in a complex situation, Rhys lost his temper and picked up little Glenys to spank her. As he strode up the passage, Nana ran after Rhys, beating on his back and saying “Don‘t Rhys, Don’t!”

In the heat of the Hastings summer, Nana rose early, often 5am, and began her cooking for us in the cooler air of the morning. An early riser myself, I would join her in the kitchen, then we would walk a couple of blocks to Findlay’s Bakery where the men were loading the bread baked during the night. Although they were not supposed to sell at that hour, Nana would kid them to sell her a hot Vienna loaf for a special breakfast for us all.

In the early 1940s, pasteurized milk was a new feature and Nana did not believe in it. We would walk to a little dark, stuffy corner store to buy raw milk in a billy. Nana would boil this and cool it (no fridge). The resulting fluid had skin and clotted cream, both of

which we did not enjoy. However Nana made a particularly delicious chicken soup and always had some ready for us when we arrived at the start of a holiday.

Nana was very proud of her cooking which was delicious but often very rich. She was lavish with butter and that probably contributed to both Nana and Grandad’s being decidedly plump. They also drank very sweet strong tea. Nana always liked to tell Mary how she made such nice food but once home, Mum kept to her own style of good nutrition.

If we misbehaved, Nana would say, “You do spoil them, Mary. You do spoil them”. This must have been quite a strain but Mum never spoke unkindly or critically to us about our grandma.

Now that I am into my later sixties as Nana would have been, I realize that having a family of five to stay for up to two weeks and doing special cooking for them, would be a considerable strain. It is not surprising that there was a fair amount of Welsh temperament about at times.

By the mid 1940s Nana had lost her singing voice and this grieved her a great deal. We are not sure how this happened. Lynne can recall her singing strongly in church, a powerful contralto. Both Glenys and I remember something about an operation but a different operation in each case. Now that I am suffering marked loss of vocal cord muscle tone in my sixties, I think that may have been at least part of the story. Nana had been secretary of the Ladies’ Guild at church for 25 years and treasured a little china basket which she was given on retirement.

All through their forty-five years after leaving Wales, Nana and Grandad held strongly to their Welsh identity. They spoke Welsh to each other and greatly valued Welsh speaking friends like the Holister-Joneses. We learnt to recognize terms of endearment and of exasperation. One valued feature of conferences like the Assembly, was that the Welsh always got together. They clearly conveyed to us the importance of our Welsh heritage and a resentment of the way that the English Industrialists and [had] treated their Welsh workers. Nevertheless they were intensely patriotic but focused on Great Britain rather than just England.

In the early 1950s they took Nana’s 84 year old brother Davy to live with them. Since his wife’s death, Davy had quarrelled with or offended each of his children and their spouses but Charlie knew how to handle Davy, and Bessie was anxious and attentive.

NANA AND GRANDAD GRIFF’S HOME

Their house, 607 Hastings Street was on a large half-acre section. The larger part of the front lawn could be used to play tennis. Behind a hedge, they had a vegie garden for which Grandad had a man come in two days a week. There was a very good asparagus bed, apple trees and a pear tree so in season, we were sent cases of fruit and parcels of asparagus in Auckland then in Feilding.

Down the back was a sort of dry creek bed and huge willows with canvas hammocks hung between them. These were sometimes full of rainwater and fallen leaves so had to be emptied out if they were to be used. In the heat, we used to lie under the gravenstien apple tree at the side of the house or the weeping elm at the front and Dad took us to swim in the Newbigan’s [Newbigin] pool across the road. (Private swimming pools were rare in those days.)

The house had had a curved bay window added to the sitting room but Nana kept the blinds down there because she had a grand royal blue and gold brocade suite in a pattern which included peacocks. We were allowed to go in there and play their old 78rpm records on the wind-up gramophone, and all have strong memories of Sandy Powell songs. Part-way up the passage was an original door with panels of deep red and blue glass.

The kitchen was very small with an early model Moffat electric stove, which had an eye-level oven. Nana kept the bread in earthenware crocks. The original washhouse and toilet were in a separate building down the back path. In the late 1940s a new washhouse and toilet were built off the back verandah. Nana also kept a canary in a cage on the back porch.

GRIFFITHS FOOTWEAR LTD

Charles Griffiths was known in Hastings as a good man, friendly and helpful. Through his warm and cheerful manner, he created a happy family atmosphere among the staff who worked at Griffiths Footwear. Most of them stayed a long time, the women leaving only when they married. When we were children, Iris Horn was in charge of the Ladies’ Department and Syd O’Neill of the Men’s Department. Grandad made Syd manager when he returned from the war and Syd bought the business after Grandad’s death. By 1952, they had seven shop assistants.

During the holidays we children were welcome in the shop and sometimes used to ‘work’ in the shop. Lynne remembers stamping and labeling shoe boxes, dusting and returning shoes to their correct boxes. She was thrilled to get payment and sign the wages book. We all remember helping make decorations for the Hastings Blossom Festival Parade: opening paper flowers for the floats took hours. One year the shop float won first prize.

SUDDEN DEATHS

Grandad’s death with a sudden heart attack in August 1953, was a huge shock to all the family. He was greeting people at the start of the evening church service when he took a first heart attack, he drove himself home and their GP gave him an injection but a second heart attack during the night proved fatal. He was 73 years old. Dad was called in the early hours of the morning and left with Mum. We girls followed by railcar once

Lynne could get across from Turakina Maori Girls’ College in Marton, where she was teaching.

At the time of the funeral, Nana followed all the protocols of her Welsh background. She had Grandad’s body lying in the open coffin in the sitting room and expected callers to pay their respects there which was a surprise to many New Zealanders. Cremation was not even considered as it conflicted with her belief in the resurrection of the body.

Nana refused to go to the funeral so Lynne stayed with her in the house at this time. For a whole year afterwards, she did not attend any public functions, not even church services nor women’s meetings. Dad and Mum went up to Hastings for a weekend as often as possible and sometimes sent one of us. Once the twelve months of traditional mourning had ended, she stepped back into her former activities.

However, Nana’s life had been devoted to her husband, and without him she seems to have lost the will to live. When she took ill, she refused to let a kind caring neighbour, Tottie Briggs, call the doctor, saying, “I’ll be alright”. Tottie stayed with her and did finally call the doctor. Nana died of pneumonia in December 1954, just fifteen months after Grandad had died.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Business / Organisation

Griffiths FootwearFormat of the original

BookCreator / Author

- Judy Breward

- Glenys Bullivant

- Lynne Milne

People

- Judy Breward

- Glenys Bullivant

- Doctor Bathgate

- Bob and Eardley Briggs

- Tottie Briggs

- Georgie Bower

- Issac Coffey

- Tom and Mary Cook

- Elizabeth Davies, nee Evans

- Rees Davies

- David Evans

- Miriam Evans

- Lizzie Evans

- Tom Evans

- Mrs Flower

- Bessie Griffiths

- Catherine Griffiths

- Charles Griffiths

- David Griffiths

- Mary Griffiths, nee McLean

- Rhys Griffiths

- Reverend Thomas Miller

- Lynne Milne

- Syd O'Neil

- Jean Smith, nee Howard

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.