- Home

- Collections

- KELSEY N

- Pioneer Families - John Davies Ormond

Pioneer Families – John Davies Ormond

Page 86

John Davies Ormond

Five people sat round the long polished dining table, set for six with crystal, silver and fine linen. Ac one end, the grey-haired mother in her fifties leant forward and said in a loud voice to her daughter, “Seddon has given permission for us to use that land.”

“What did you say?” shouted the daughter.

Her brother sitting beside her interpreted loudly, “She said Seddon has sent a mission to Switzerland.”

“How extraordinary. I thought he was Minister for Native Affairs,” mused his sister.

“What did she say?” roared her mother,

“Extraordinary man. She heard he was having an affair!” bawled her son.

And so it continued, as it did every meal time, for Hannah Ormond, her daughter Fanny, and Frank, Hannah’s second son, were deaf. Even with the help of their hearing aids, conversations took much longer than normal: the aids were like ebony fans which, clenched between their teeth, conducted noise along the wood, through their teeth and up into their auditory organs. That was the theory anyway; no one would have called it a successful method, and it certainly slowed down the eating process.

Also seated for the meal were Geordie, Hannah’s brother, a very large man in his middle fifties, and her youngest son Jack. They talked in voices raised enough to make themselves heard above the shouts of the others.

Then, as Hannah’s husband, white-haired and bearded, entered and took his place at the head of the table, the talk ceased and the only sound was of cutlery on bone china. John Ormond, known to friends as “The Master” or J,D., made his presence felt.

In Britain in 1846 the beautiful Adelaide Ormond caught the eye of Edward Eyre who had an enviable reputation as an explorer but no job.

When Eyre later landed the post of Lieutenant-Governor in New Munster in New Zealand, probably as part of a plan to keep in touch with the family, he

Photo caption – John Davies Ormond

Page 87

asked Adelaide’s younger brother John to go to New Zealand with him as his confidential clerk. J. D., a fourteen-year-old boy destined for a possible career in the navy, jumped at the chance, and his parents did not object. He was the fourth child and third son of Francis Kirby Ormond, a retired naval commander, and his wife, Fanny (nee Hedges). They had moved to Plymouth from Wallingford, in Berkshire, a decade after J. D.’s birth in about 1831.

J. D. was sixteen by the time he arrived in Auckland in December 1847, off the Ralph Bernal. In a letter to a shipboard acquaintance he comes through as a cheerful, friendly boy, not at all the anti-social, taciturn man he later became.

After some time in Auckland, he travelled to Wellington with Eyre, to both work and live in Government House. It was a decrepit building: they slept on mattresses on the floor, avoiding drips from the leaking roof, and sat at their desks in hats and overcoats because of the cold wind whistling through the rooms.

Eyre soon became a figure of fun in Wellington. He was a fussy, pompous man, and given to wearing full dress-uniform all the time, which, complete with silver braid and gold lace, did not look so well under an overcoat!

By October 1849, J. D. had proved himself useful, and had been promoted to Private Secretary, and Clerk to the Executive Council, at £200 per annum. He must, however, have been lonely during this time, having little contact with people of his own age. It was probably shyness, but he began to be known as “bumptious” and was already becoming rather reserved.

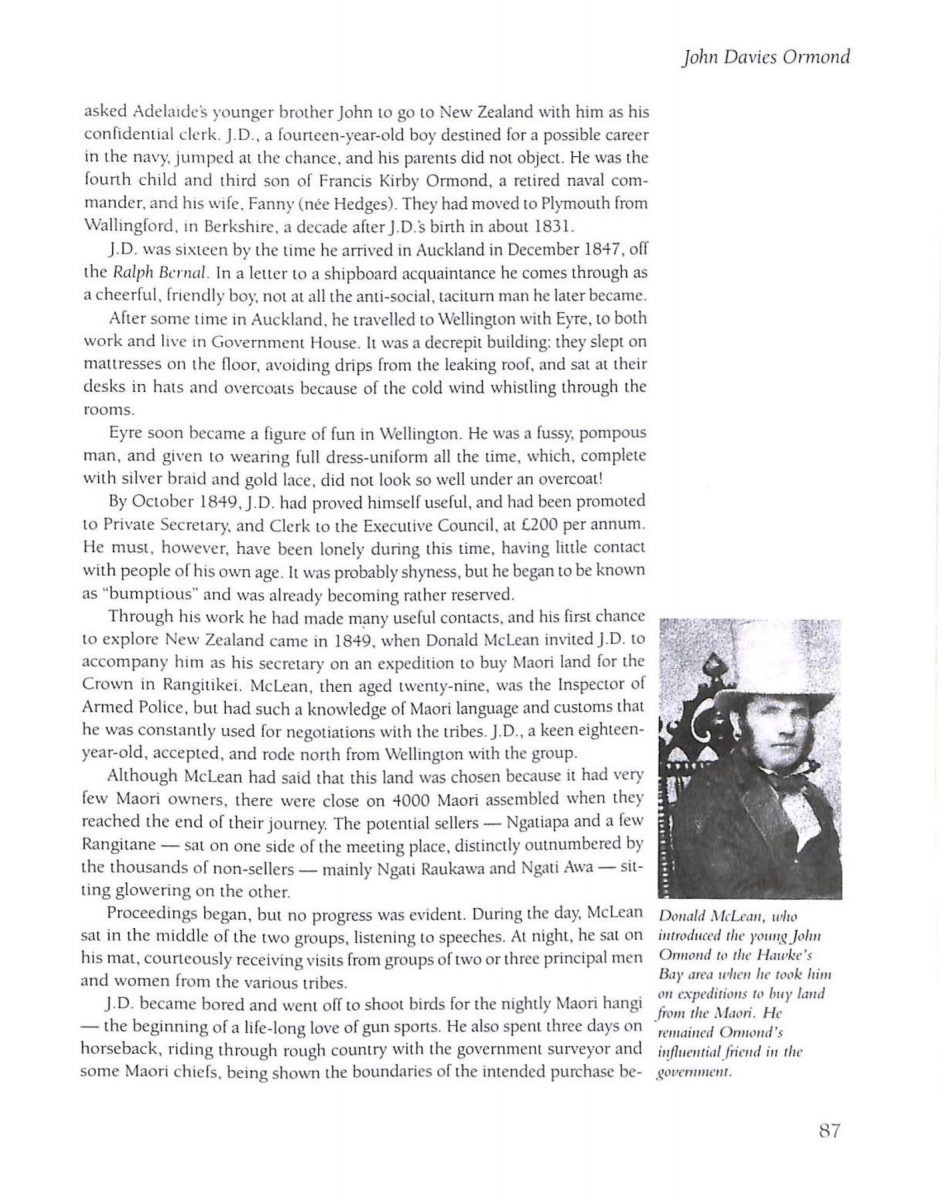

Through his work he had made many useful contacts, and his first chance to explore New Zealand came in 1849, when Donald McLean invited J. D. to accompany him as his secretary on an expedition to buy Maori land for the Crown in Rangitikei. McLean, then aged twenty-nine, was the Inspector of Armed Police, but had such a knowledge of Maori language and customs that he was constantly used for negotiations with the tribes. J. D., a keen eighteen-year-old, accepted, and rode north from Wellington with the group.

Although McLean had said that this land was chosen because it had very few Maori owners, there were close on 4000 Maori assembled when they reached the end of their journey. The potential sellers – Ngatiapa and a few Rangitane – sat on one side of the meeting place, distinctly outnumbered by the thousands of non-sellers – mainly Ngati Raukawa and Ngati Awa – sitting glowering on the other.

Proceedings began, but no progress was evident. During the day, McLean sat in the middle of the two groups, listening to speeches. At night, he sat on his mat, courteously receiving visits from groups of two or three principal men and women from the various tribes.

J. D. became bored and went off to shoot birds for the nightly Maori hangi – the beginning of a life-long love of gun sports. He also spent three days on horseback, riding through rough country with the government surveyor and some Maori chiefs, being shown the boundaries of the intended purchase between

Photo caption – Donald McLean, who introduced the young John Ormond to Hawke’s Bay area when he took him on expeditions to buy land from the Maori. He remained Ormond’s influential friend in government.

Page 88

Pioneer Families

the Turakina and Rangitikei Rivers.

The first sign of progress occurred just as he returned, when the Whanganui chiefs left the side of the non-sellers and moved across to settle down among the sellers and original owners, the Ngatiapa. Imperceptibly, every morning after this, the ranks of the sellers increased until they were obviously in the majority.

The deed of sale was eventually signed by all the main participants, and the purchase of Rangitikei was achieved. McLean had achieved his goal: about 200,000 acres at 2½d. an acre.

J. D. never forgot that unique sight: thousands of Maori negotiating to sell their ancestral lands, over which they had fought each other for centuries, with an almost complete absence of conflict. It was a lesson in patience and cultural adaptation that he always valued.

In 1852, J. D. bought 500 sheep, arranged grazing for them on a friend’s pastures at Te Ore Ore, and resigned from government service to make a brief foray into the Australian goldfields. If he hoped to make money to invest in his own grazing, he was unsuccessful; but on his return in 1853, he accompanied McLean to Napier on another government land-buying expedition. Being four years older and more experienced, he had no qualms about using his privileged position and inside knowledge to acquire land for himself on this trip. There were thousands of acres of Maori-owned land available in Hawke’s Bay, and, although the Maori were supposed to let only the Queen have their land, J. D. bartered successfully with them for about 4000 acres in the Porangahau area, at a lease of approximately a farthing an acre. He immediately cut a track overland through thick bush (Forty Mile Bush) from Te Ore Ore to Castlepoint

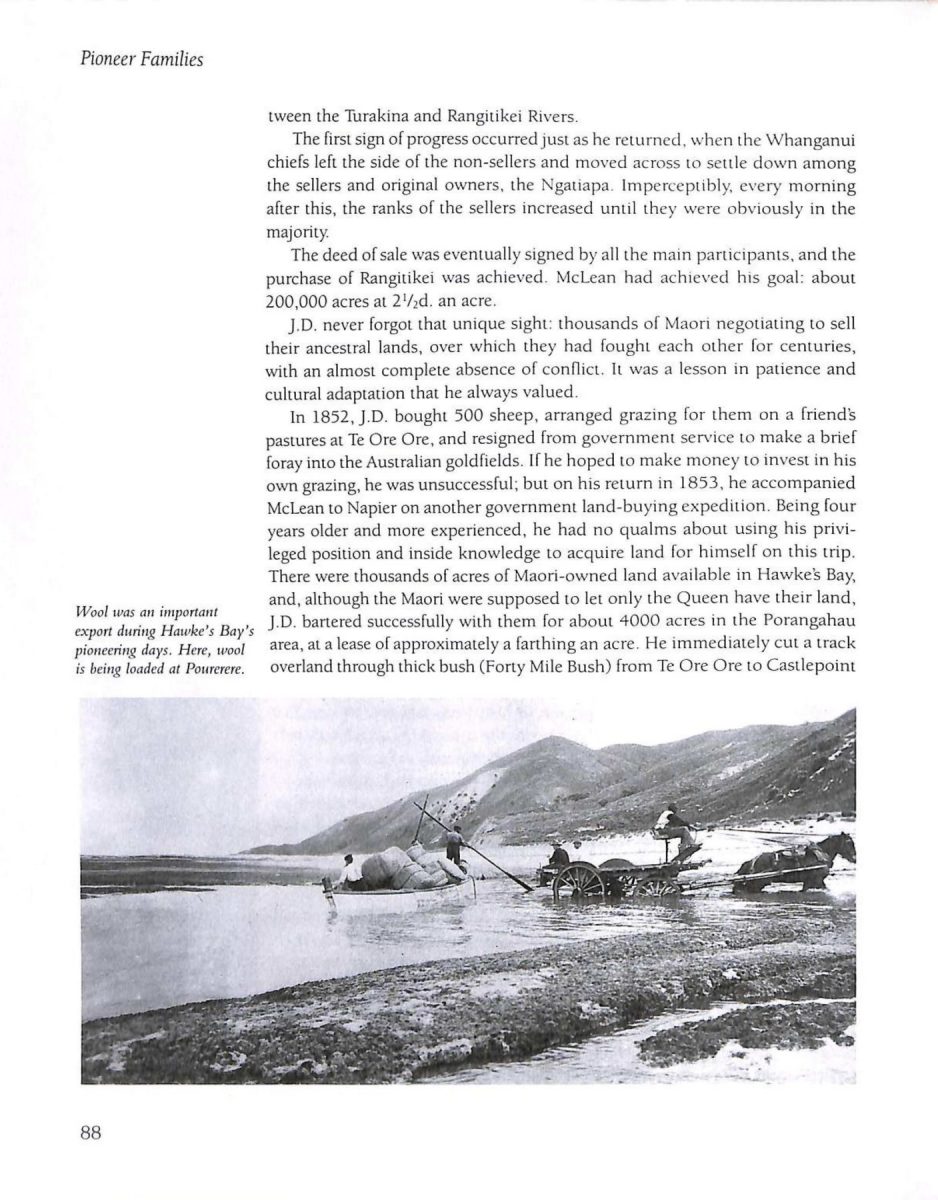

Photo caption – Wool was an important export during Hawke’s Bay’s pioneering days. Here wool is being loaded at Pourerere.

Page 89

John Davies Ormond

– shortening the usual route along the coast by days – and drove his flock through to his own property at last.

Between 1853 and 1859. J. D. must have toiled ceaselessly. There was some natural grazing on his land, but with no fences he had to be his own shepherd, keeping the animals together and moving them from place to place, making sure they had shade and water, and did not fall down gullies or wander into swamps. The rest of the property was mostly hilly and very dry, and covered in vegetation, but it was well-adapted for sheep when burnt off. Therefore, in between shepherding, he had to fire it in blocks, sow grass seed in the ashes, and construct whatever fences he could afford. He also had to bring in provisions to house, feed and clothe himself, dag and shear the sheep, and get the wool to market. In between times, he sometimes took messages as far as Auckland and Wellington as a despatch rider for Governor Gore-Browne. “No war could have been half as exciting,” he said later.

He was now twenty-one, and, as the son of a penurious naval officer, he had absolutely no experience in farming, but lots in thrifty living. As a government servant, he had learned daily how settlers were managing on the land, and had made useful contacts. He flourished.

Of course, the government caught up with him and others like him when, in 1856, McLean, who had turned a blind eye to the illegal squatting, was replaced as land purchaser in Hawke’s Bay. The new incumbent was a stickler for the rules, and insisted that the squatters “pay up their leases and clear off the land” until such time as the government bought it from the Maori.

But by now J. D. had increased his flock to 2600, and he organised a protest petition. He rode hundreds of kilometres in all weathers to collect signatures, which he sent off with a polite official letter on the settlers’ behalf, pleading their case to the Superintendent of the Wellington Province, Dr. Featherston. However, in a private letter he wrote to Featherston he was aggressive and demanding, saying that the settlers would be ruined and that they would “defy the law and let it do its worst”.

Featherston was flummoxed. The government did not have the money to buy the land, and so he called in J. D.’s friend, McLean, who negotiated an acceptable purchase price within the government’s limits. J. D. and his fellow settlers breathed freely again, and he wrote apologetically to McLean about the strife he and the other settlers had caused; but before long, he was using his friendship with McLean to acquire more questionable holdings.

He was also, inevitably, moving into the political arena of the developing country. Hawke’s Bay was then part of Wellington Province, whose coffers had been swollen by the £20,000 the squatters had paid to legitimise their tenure. But the government had not provided the roads and bridges so necessary for the transport of stock and provisions. The squatters, J. D. in the forefront, started a strong movement for Hawke’s Bay to manage its own affairs. They agitated and campaigned effectively, and on 1 November 1858 Hawke’s Bay became a

Page 90

Pioneer Families

separate province. J. D. was one of ten representatives elected to the new Hawke’s Bay Provincial Council in March 1859, and within the month he was elected Speaker.

“ … eager, impulsive, ambitious, voluble in rapid, close-clipped speech … nervous strength… hasty yet calculating,” was a contemporary description of this twenty-seven-year-old man whom Hannah Richardson met a year after she and her mother came to live in Napier, and who became her husband.

Hannah Richardson had confided to her diary as she grew up that she planned to “live and die an old maid”. Although she had many suitors, she adored her brother, Geordie, who was two years younger, and sought nothing more than to look after him for the rest of her days.

This self-effacing image is surprising, considering her attributes. Born on 14 June 1833, she had benefited from a good education, was intelligent, widely read, a skilful sewer and embroiderer, an accomplished musician, and surprised her contemporaries by the wide range of subjects she enjoyed discussing – biography, history, theology, Parliamentary reform and European affairs among others – not the usual topics of conversation for a woman. This could have explained her popularity with the opposite sex: men found her an attractive, sensitive and appreciative companion, and she herself enjoyed their company. Along with her mother, she extended a warm welcome, music and good conversation to many who came into their hospitable home.

Hannah and Geordie were the only two children of Mrs Jane Douglas Thomson, a Scottish woman, twice widowed, who now lived with and for her family in Scotland. Geordie, however, had left them to emigrate to Napier, New Zealand, in 1857, aged twenty-one. Mrs Thomson owned a little house but, deprived now of day-to-day funds from her son’s earnings, she decided to emigrate too. Certainly Hannah had no other goal in life than to follow him. She and her mother sailed from Gravesend on the Evening Star on 15 September 1858, taking with them the usual luggage, plus a piano and a servant girl, Jane Gunyan.

After the gruelling, boring and uncomfortable voyage, they reached Napier on 15 January 1859, but the wind and tide were against them and they had to drop anchor three kilometres from the shore. Geordie rowed out in a little dinghy through heavy seas to greet them and, although the weather did not improve, took them back with him, though Jane Gunyan had to wait. So they landed in New Zealand for the first time, thoroughly drenched from waves and rain, at the only possible point, on the shingle spit, and had to wait an hour before the tide dropped enough to allow them to cross to the town. Their luggage was landed the next day, along with the ship’s cargo, mostly packed into barrels so that it could be dumped off a barge onto the spit and rolled

Page 91

John Davies Ormond

from there to solid ground.

They were amazed by Napier: it was almost an island – a steep hill, flat at the top and split by steep ravines – joined to the mainland by two extensive spits of sand, shingle and shells. One of the spits was almost eight kilometres long and enclosed an immense lagoon about three kilometres wide. Fresh water was very scarce, and only available some kilometres inland, at a very great depth.

They heard the place given different names: Mataruahou, Napier, Scinde Island. The Europeans could not decide with which name to commemorate Sir Charles Napier’s recent victory at Meeanee in the Indian province of Scinde. Clive, the principal town not far away, also had an Indian connection.

They saw the men of Napier with guns under their arms, ostensibly for the shooting of wild pigs, but Hannah and Mrs Thomson soon became aware that there was friction between two chiefs, Te Hapuku and Te Moananui, and that troops had been called in in case of trouble. They were assured that there was no real danger, and that the soldiers were only there to dissuade the Maori from bringing their quarrels into town.

There were about 370 people living in Napier then. Mrs Thomson bought the only suitable four-roomed house available for the family – in Carlyle Street – for £300, and they moved in two days later. It was a squeeze, for Geordie came too, but Jane slept on the floor if unexpected guests needed a bed, and they managed. However, when Jane left to marry within six months, it was quite a relief in one way.

In another, it was a calamity. With no maid, Hannah and her mother had to start doing housework, which they had never done in their lives before. Hannah

Photo caption – Napier in 1864, which J. D. was shortly to represent as M.P.

Page 92

Pioneer Families

filled her diary with details of her hard labour, and consequent bouts of weeping. These seemed to make her feel better, but other aspects of her new life also depressed her; the climate was unpredictable, and the house looked out onto bulrushes and was surrounded by stagnant water, leading to stomach troubles and headaches, along with itchy battles with mosquitoes. Dung and fleas were everywhere, with domestic animals roaming freely, and sometimes dying in the street. One day, noticing a very offensive smell in the back bed room, Geordie lifted the floor boards and discovered a decomposing pig.

Hannah also found this rough little settlement deadly dull, until she and her mother resumed the convention of calling on neighbours and leaving visiting cards. Within months their house was again full of visitors, and they began to enjoy many new friends.

Geordie had made other acquaintances in the trading and shipping world, and made it quite clear that he had no wish to have his devoted sister as his slave. He was a genial, untidy giant, who gathered with his cronies and contacts in bars and public houses until late at night. Hannah began to despair of his friends, his drinking and his thoughtlessness when he invited people to stay without telling his mother. Mrs Thomson did not seem to mind, and willingly slept on the floor if necessary, which made Hannah all the more annoyed.

On top of all this, Hannah was going deaf. However, she indulged in no self-pity, except to record that it interfered with her music, and that she might have to withdraw from running the choir at their local church.

It was about this time that Hannah first met her future husband. When J. D. came to Napier to attend Provincial Council meetings, Geordie, who was at that time auditing the Provincial Council accounts, began helping him through his shipping and business connections. J. D. became a frequent guest at the Richardson home, where he attracted Hannah’s interest although not her fancy. Compared to other men with whom she was mixing, he did not stand out in any way, except that he did not seem to be impressed by her. And she didn’t find J. D. an easy guest. He was inclined to be somewhat “haughty and rude”, according to her diary, but he had a certain presence, and was included by Hannah and her mother when they were entertaining. He came to a “rather grand dinner party” in April 1859 for Mr and Mrs Purvis Russell, people of “wealth and importance” in the area, and also to a “monster picnic” which Hannah organized, with her mother as chaperon. Along with Mr Tucker, one of Hannah hopeful suitors, he was asked to arrange the lunch, and provided a veritable feast complete with turkey and champagne. They were all rowed across the inner harbour in two boats by soldiers from the garrison, singing into the darkness on the return trip, after which Tucker and J. D. went back for supper with Hannah and her mother.

Another time, they all rode in the same group to a grand housewarming party given at the Henry Russell home at Mt Herbert, taking three days to

Page 93

John Davies Ormond

make the journey, with nights in settlers’ homes along the route. There was luxury, grace and charm the whole way, and Hannah found herself in a black mood when she returned to the drudgery and trials of home. She had not spent much time in J.D.’s company at Mt Herbert, but had been touched by his attentive and thoughtful company on the ride home, and wrote later in her diary that she was considering him as a husband.

She was now twenty-seven, but was puzzled as to “why I should feel more readiness to put my fate into the hands of one almost a stranger to me” instead of remaining single as she had always planned. Despite this, she was stunned when Geordie said one day that J. D. was coming to visit and “… it’s about you & I told him I thought it was alright & he better talk to you.” J. D. did come that evening, and during the next few days, yet he said nothing of a personal nature, and Hannah was left feeling very uncertain, until, on 17 August 1860, he visited her again. Her journal entry simply says; “Mr Ormond came down after dinner & we came to an understanding.”

There was no declaration of love on either side. McLean had recorded earlier that Ormond wanted “an excellent amiable girl – with careful prudent habits”, and Hannah’s journal entries, immediately after her wedding was announced, are concerned not with her emotions but with other matters. She mentions J. D. only twice; once to indicate that she thought they both enjoyed the same books; and another time to record “Mr Ormond is very anxious to be near my mother and Geordie for my sake and probably some arrangement will be made for our residing in Napier.”

Despite Hannah’s hopes, after their marriage on 4 December 1860 by the Rev. Samuel Williams in the new church at Te Aute, they rode straight from the church to “Wallingford”, J. D.’s house, named after the place where he was born. At that time “Wallingford” was not much more than a shack, sixty-five

Photo caption – The Ormond homestead “Wallingford”, 120 kilometres from Napier, after many additions to the mere shack J. D. owned when he married Hannah.

Page 94

Pioneer Families

kilometres out of Porangahau, and 120 kilometres from Napier, set in the 5000 odd hectares J. D. now farmed. The records show J. D. as giving his bride a roll of while flannel for a wedding present, with which to make herself a coat, and, in the same practical vein, there was no honeymoon.

That was how it was right from the beginning. Hannah had known J. D. only as an acquaintance, mainly well-mannered and helpful, but had not realised he was also utterly self-reliant, and could be uncompromising and over bearing. It was just as well that Hannah had had an inclination to dedicate her life to her brother; it made it easier for her to switch allegiance to her husband, and to give him the unquestioning obedience necessary for the successful operation of their marriage. Immediately after their wedding. J. D.’s political life burgeoned, his properly acres multiplied, and he became deeply enmeshed

Text on map – Petane River, Pitohawea, Upokaopoito, shingle beach, Kopaki, KO TE WANGANUI ROTO, pa, Ohingora, Meeanee Spit, breakers, breakwater, Te Whatapuka, rocks, principal road, Mataruahoe, Scinde Island, approximate sight of Richardson home, Rauwera, Napier, sandy bank uncovered at low tide, covered during floods, very shallow lagoon, mud flats, Tutaekuri River.

Map caption – Napier as it was before reclamation, when Hannah Richardson lived there. J. D. was to be a prime mover for the improvement of conditions in the town. At this time it had open sewers, fetid swamps and no town water supply.

Page 95

John Davies Ormond

in public responsibilities. He needed her total support as he moved constantly between “Wallingford”, Napier and Auckland over the next eight years, after he was elected M.P for Clive in February 1986.

Their first child, George Canning Ormond, was born in Napier in November 1861. After the birth Hannah had to ride all the way home round the coast, with her tiny baby and J. D., staying a night with friends on the way. However, by the time Fanny their second child was born, again in Napier, early in 1863, there was a bullock track back to “Wallingford”. The journey was slightly more comfortable for mother and baby, but it still took three days. They spent one night with Sam Williams at Te Aute. Mrs Williams greeted them warmly, went to a cupboard and took out their sheets, clearly named after their last stay, and made up their bed. When they left the next day, she folded and named the sheets again and put them away until their next visit. She had so many visitors, and it saved so much washing!

This year, reports of fighting with the Maori elsewhere in the country filled the newspapers, and the Hawke’s Bay people turned to J. D, for advice. This irked his old acquaintance Henry Russell (nicknamed Lord Henry), who, as titular sheriff of the area, considered that he should have been approached, and, although the trouble simmered down, antagonism lingered.

However, by October, the land troubles with the Maori reached Hawke’s Bay. A force of Hauhau travelled into the district, bent on attacking and looting Napier and killing its inhabitants. There was real menace here and, as Member of the House of Representatives, J. D., along with his friend McLean, was present when a hastily assembled force, half European and half loyal Maori, overwhelmed the enemy at Omaranui. There had been plans to evacuate the wives and children to Wellington, but Hannah remained at home and, as one local settler wrote to McLean, “Ormond remaining where he is with his family makes me feel truly safe.”

By 1865 the area was peaceful again and “Wallingford” had grown to about 6000 hectares. Their house was now sizeable after considerable additions, and with many farm staff, J. D. could spare time occasionally to indulge his sporting interests. He still loved to get out with his gun, and he and McLean imported birds such as grouse and thrushes for both game and sentimental reasons; while later J. D. brought in trout and salmon ova from San Francisco to indulge his fishing interests. He also had a growing number of racehorses, and in 1866 he helped found the Hawke’s Bay Jockey Club.

Hannah was coping with the stresses of homemaking and childbearing with her husband frequently away. Her mother assisted when she could. In 1867, their third child, Carrie, died in infancy, and although J. D. commented in a letter to McLean that “my poor wife feels this bereavement sadly”, all his thoughts, energies and efforts were focussed on his farming and political responsibilities.

He had no time for, or patience with, an emotional wife, and when Hannah

Photo captions –

George Ormond.

Fanny Ormond.

Hannah Ormond and her eldest son, George.

Page 96

Pioneer Families

had another baby, Frank, in 1868, and found herself exhausted and prone to bouts of tears, he reacted unhelpfully. Mrs Thomson persuaded him that it was a not unexpected reaction after childbearing, and came to stay, tiding Hannah over the worst period. She finally remained in a permanent capacity, helping with all facets of the home and expanding family – Ada came in 1872 and John Davies Junior, “Jack”, in 1873 – and encouraging Hannah to spare her extremely busy husband the distractions of noisy children and mundane matters.

Again mother and daughter created a welcoming home. Travellers often called, and were greeted with meals and a bed for the night. Mrs Thomson willingly slept on the drawing room sofa more than once; but should J. D. be home, the travellers were sent on to the Wallingford Hotel for, if guests were forced on J. D., he would simply disappear. Once he blew his top and announced “he was going to have a headache” and lay down on the sofa in front of everybody. They had dinner without him, and then Hannah entertained around him.

By now, the pattern of the future years was emerging: the world revolved around J. D., and when he was at home, Hannah and the family tiptoed round the house, keeping out of his way while he held meetings, or sat in his study reading newspapers or cogitating about politics or land deals. He and McLean put their heads together about several projects, having some disregard for the legal niceties, including land J. D. bought in the early 1860s in the Manawatu area, midway between Dannevirke and Woodville. Secrecy seemed essential, for “when it is known that you and I have taken steps toward securing runs there, there will be a regular rush for it,” wrote J.D. to McLean.

At yet other times, instead of acquiring land, J. D. used his inside knowledge to sell. In 1869, at the age of thirty-seven, J. D. became Superintendent of Hawke’s Bay and Agent-General, and in this capacity he visited the recently established Scandinavian settlements at Dannevirke and Norsewood. He was sincerely impressed, complimented them on the excellence of their developments, arranged for schools to be built and equipped, and for road access to be provided. The little town thus fostered was named Ormondville in his honour. And, of course, the roads also gave improved access to his Manawatu land, which, having owned it for just seven years, he was able to sell at a very nice profit. This money went into a Crown purchase at Woodville he had just heard about.

By now he had increased his hectares at “Wallingford” to about 8000, by various means, and was grazing about 25,000 sheep under Tom Midgley, who managed the property for him for thirty-four years.

J. D.’s doctor brother, Fred, who emigrated to New Zealand after J. D., had not been so successful. Fred’s land speculations had him facing bankruptcy, and, although extremely well-off by now, J. D. made no apparent effort to help him. It was McLean who bought Fred’s farm in a mortgagee sale and let Fred

Photo captions –

George Ormond holding John Davies Junior, “Jack”.

Frank Ormond.

Ada Ormond.

Page 97

John Davies Ormond

Ormond and his family stay there. Hannah was mortified by J. D.’s lack of support, and lamented his stinginess. She wrote: “I chafe at having so little power to do anything for anyone with all our riches.” However, she had her sewing machine, and she and her mother did what they could:

Finished 6 nightgowns for the Ormond cousins… I made four pairs of drawers for Mrs Ormond, 2 frocks & four pairs of drawers for Harriet. . . Mother got together what we have made for Mrs Ormond’s children & with them a few things my bairns can do without.

It was about now that J. D.’s next contretemps occurred with Henry Russell. J. D., Henry Russell and his brother, and others, had acquired land on the Heretaunga plains nine years previously, by allowing the Maori owners unlimited credit for goods, and then demanding payment. Because the Maori had no money, they had to pay with their land, and J. D. and his friends became notorious as “The Twelve Apostles” or “The Forty Thieves” when the Maori people later complained bitterly over the whole train of events.

However, the “Apostles” were found not guilty by the Native Lands Alienation Commission at a hearing in 1873; but then Henry and Purvis Russell, former owners with J. D. of that land, became extremely righteous and started the Repudiation Movement, suggesting all land acquired by Europeans from Maori should be forfeited. J. D. was incensed by this stab in the back, and a bitter campaign, vitriolic on both sides, ensued.

In one attack, J. D. tried to have the Russells expelled from the Hawke’s Bay Club, which he had helped to found in 1863. When that manoeuvre failed, he ostentatiously refused to patronise the Club if they were on the premises. In the end, he used his influence with banking acquaintances to deny funds or overdrafts to the Repudiation Movement, which finally folded. J. D. was heard to wish that “those cursed Russells” would return to England, in which case “Hawke’s Bay would be purified.”

At home, J. D. found he had almost no further energy to communicate with Hannah; and when Fanny, Frank and Ada all became deaf too, it became easier simply to give orders, to be obeyed immediately and without question, and to live by well-ordered habits, so that nothing much had to be said.

The family co-operated understandingly, but Hannah knew that the children needed social contact in their own home. As the family grew older, when J. D. went away a metamorphosis occurred. Guest lists were written, a day was chosen, invitations were issued, and the whole house was readied for the exciting festivities. Even “The Master’s” study was used as a servery for claret cup or hot coffee. The guests, who all connived behind J. D.’s back, would arrive, pile their coats in one of the bedrooms and plunge into the party.

On one occasion J. D. came home unexpectedly: everyone froze. One account of the incident said that when he threw open the front door and stood there without saying a word, conversations petered out, the guests collected

Page 98

Pioneer Families

their wraps and coats, whispered their farewells and departed. Then “The Master” shut the door and, still silent, went to bed. In the other version, J. D. is said to have simply stormed straight upstairs, thrown all the coats and wraps onto the floor, climbed into bed and gone to sleep. The story does not indicate whether anyone was brave enough to collect their outerwear before they left!

He was probably “the Hon J. D.” by then. He had achieved cabinet rank as Minister of Works in 1872, but the government went out of office the next year. The year 1874 finally saw him turning his attention to the unsatisfactory conditions in Napier, where they had lived since he became Superintendent of the province. One wonders why Hannah was so fond of it: there were constant clouds of dust, open sewers, fetid swamps still undrained, absolutely no fire-fighting facilities because of the lack of a town water supply, garbage every where, and terrible roads.

J. D. encouraged the residents to form a borough, which enabled them to raise loans for the necessary town works, and in 1875 he was one of the working party which lobbied for the implementation of free State Education in the province.

Through all these years, he had to do most of the mundane work himself. He had a secretary in Wellington, but no one at home, and he wrote all his letters by hand. Once, he penned an urgent letter to Dr. Featherston in Wellington, and then rode from “Wallingford” to Napier, via Tamumu, Middle Road, and Havelock North, a distance of 118 kilometres, so that he could put it on the boat sailing for Wellington that night.

In 1876 the tide started turning against him. The provinces were abolished and he was no longer Superintendent; and after a short spell in his old post as Minister of Public Works, the government fell during its term. J. D. was appalled to receive part of the blame for creating a turmoil “unparalleled in the annals of the New Zealand Parliament”. All he had done was counter the accusations of wrongdoing made against him over the Heretaunga block. Admittedly, he had included George Grey in his scathing comments, but he saw it as only normal parliamentary-style debate.

On 5 January 1877, McLean died. The whole country mourned him, Maori and Pakeha alike, and J. D. lost his best friend and an influential political colleague. He was increasingly aware of the animosity of his enemies. He did his best at all times, but the praise he received did not seem to balance the vilification, and he kept to himself more and more.

But worse was to come. Having been mentioned as a possible Premier, it was unbelievable when he lost his seat to a Waipukurau storekeeper in the 1881 elections. After twenty years as M.P. for the area, his stature had declined. He was in and out of Parliament for the rest of the decade, and decided that it was time to retire from active politics in 1890, aged sixty-eight, although he accepted appointment to the Legislative Council in 1891.

Through all this, he had been spearheading a movement, as chairman of

Page 99

John Davies Ormond

the Napier Harbour Board, to raise the harbour’s facilities to the national level by having a breakwater built. The black days of rejection by the electorate were mitigated by the sight of bunting on ships and buildings on the day Hawke’s Bay voters agreed to this move; and by his being drawn in triumph “by four greys harnessed to a magnificent carriage” to lay the first block of the breakwater in 1887. The variety of businesses and the prosperity of the area were in no small way due to the well-dredged, deep-water port he had worked so hard to promote.

J. D. and Hannah were now living at “Tintagel”, the home J. D. had built in Napier in 1884. He had to supervise both “Wallingford” and “Karamu, on his 500 hectares on the Heretaunga plains, where he kept his large stud of Clydesdale horses, which won him prizes all over New Zealand, along with his Shorthorn cattle and Lincoln sheep. The avenue of oaks he planted along the drive to “Karamu” became Oak Avenue in Hastings.

However, racing now became his major interest, both as a committee member of the Hawke’s Bay Jockey Club, and as an owner at meetings round the country, where his stable’s bright cerise colours gave him many thrills. In 1906 he had more horses racing than any other owner in New Zealand, and he had bred most of them himself. In 1887 he was involved in the founding of the New Zealand Racing Conference, and was proud to be elected Hawke’s Bay’s representative. He remained in this post until his death in 1917, being president of both that and the Hawked Bay Jockey Club at one time or another.

Occasionally Hannah and Fanny went to the races with him, especially if he really thought that one of his horses might win. On one such occasion, they

Photo caption – A view of Napier prior to reclamation in 1908. These marshes were overlooked by the Richardson’s house.

Page 100

Pioneer Families

were so busy catching up with their friends that they completely missed the main race of the day. Suddenly Hannah’s voice boomed out above the crowd, ‘We must turn round, Fanny. I believe the horse has won.”

As the family assumed more of J. D.’s responsibilities, married and moved away, J. D.’s daily routine became sacrosanct. He spent the mornings inspecting his animals at “Karamu”, before having a biscuit and glass of port at home for lunch and then heading off to the Club. In these later years, he was never known to speak to anyone, have a drink with anyone, or take part in any Club affairs. He simply read the newspapers at length, then turned for home again, where he inspected and watered the garden until dinnertime. This meal was the main event of the day, starting at 8 p.m. and often not finishing until after 10 – not surprising, given the slowness of the conversation!

The meal had to be perfect; meats of the best quality, supplemented by the quail, grouse and pheasant he had imported; fresh homemade butter, and the vegetables and fruit picked just before the meal, often by himself. There were no condiments on the table; everything had to be perfectly seasoned to his taste in the kitchen; and he helped the food on its way with half a bottle of claret from his cellar.

Hannah insisted that several grandchildren from the country live at “Tintagel” in term time so that they could be educated at the Napier school. J. D. seems to have made no protest. Although he was mellowing in his retirement, those grandchildren were very much in awe of him and kept out of his way; so one of them was astonished to hear their grandmother having the temerity to say to him, when he helped himself lavishly to an unusual delicacy on the dinner table, “John, your eye is bigger than your stomach!”

Fanny never married, and she was her mother’s best friend. Together, they managed the house, entertained, enjoyed their music, ministered good works and kept J. D. uninterrupted and happy. Whenever he arrived home, he expected them to be there, drop everything, and run to the door to greet him. On one occasion he arrived home early to no such fuss. The two women were doing charity work at the hospital. He is reputed to have shown his displeasure by instructing the chauffeur not to fetch them as arranged, but to “let them walk”.

J. D. himself became infirm as old age crept up on him, but he still pursued his pleasures and his duties. The day before his death, although he was unwell, he insisted he would go to the Club as usual; and when he died on 6 October 1917, the family could hardly believe it, because it was not in his plans! Hannah lived on, peaceful and serene, well looked-after by her offspring, and active and agile. Aged ninety-six, having been advised to rest, she secretly climbed down a steep fire escape to see her newly born great-granddaughter. Had she not broken her hip, her doctor predicted she would have lived to be a hundred.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

The donor of this material does not allow commercial use.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Description

From “Pioneer Families – The Settlers of Nineteenth-Century New Zealand” by Angela Caughey

Subjects

Format of the original

Book excerptDate published

1994Publisher

David Bateman LtdPeople

- Edward Eyre

- Doctor Featherston

- Governor Gore-Brown

- George Grey

- Jane Gunyan

- Donald McLean

- Tom Midgley

- Sir Charles Napier

- Ada Ormond

- Adelaide Ormond

- Carrie Ormond

- Fanny Ormond

- Fanny Ormond, nee Hedges

- Francis Kirby Ormond

- Frank Ormond

- Fred Ormond

- George Ormond

- Hannah Ormond, nee Richardson

- John Davies Ormond

- John Davies Junior (Jack) Ormond

- Geordie Richardson

- Henry Russell

- Mr and Mrs Purvis Russell

- Mrs Jane Douglas Thomson

- Mr Tucker

- Reverend Samuel Williams

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.