- Home

- Collections

- HAYWOOD BJ

- Tales of Pioneer Women Excerpt

Tales of Pioneer Women Excerpt

TALES OF

PIONEER WOMEN

COLLECTED BY

THE WOMEN’S INSTITUTES OF NEW ZEALAND

WITH FOREWORDS BY

A.E. JEROME SPENCER, O.B.E.

Founder of Women’s Institutes in New Zealand

AND BY

AMY G. KANE

Dominion President, New Zealand Women’s Institutes

SECOND REVISED EDITION

FOR HOME AND COUNTRY

EDITED BY A. E. WOODHOUSE

WHITCOMBE & TOMBS LIMITED

CHRISTCHURCH, AUCKLAND, WELLINGTON, DUNEDIN, INVERCARGILL

LONDON, MELBOURNE, SYDNEY

1940

Page ix

Foreword

By A. E. Jerome Spencer, O.B.E., Rissington W.I., Founder of Women’s Institutes of New Zealand

It is fitting that a book of pioneer tales by the Women’s Institutes of New Zealand should include some account of the pioneering days of the Women’s Institute Movement itself in this country. As the tales do not aspire to be a history, so this brief sketch does not aim to be more than a few notes of those days.

Perhaps the first adumbration of what was to come may be traced to the moment, during the Great War, when my friend Mrs. Francis Hutchinson, of whose home I was a member, remarked on the loss of our little country district of Rissington would suffer when the meetings for Red Cross work should come to an end, and expressed the wish that some women’s society could be devised to carry on in our neighbourhood the spirit of fellowship and co-operation that had grown out of the grim needs of war. Soon afterwards, at the end of 1916, I travelled to England to do war work. In 1918, when engaged on night work in London, I happened one afternoon to be in Westminster, and noticed on the Caxton Hall a large placard announcing within a display of Women’s Institute Handicrafts. Attracted by the first and third of these words, but totally ignorant of the implication of middle one, I went in-and found the answer to Mrs. Hutchinson’s wish. A chance meeting later with an ardent president of a County Federation, and a visit to Headquarters in London, supplied me with enthusiasm and the necessary information and literature. On my return to New

x TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

Zealand at the end of 1919, my friend and I took counsel together, and in February, 1921, at a little meeting on the wide verandah of her home, Omatua, the Rissington Women’s Institute was launched. When this first Institute was well established and was becoming known through newspaper reports of its work, a request was received from Norsewood, a small village some eighty miles away, that I should help to form one there. This came through the doctor’s wife who had been a member in England. The little settlement of Otawhao was the next to follow suit. Gradually the need for systematic organising, to establish this great movement well and truly, was borne in upon me, and it became evident also that, since I was free and informed, it was upon me that this task devolved. From this time until 1933 my years were filled with incessant work, travelling, speaking, writing, planning. When there were eight scattered Institutes, representatives came to Rissington from varying distances up to 100 miles or more, and the first federation, the Hawke’s Bay Federation, was formed. This acted as “mother” to new Institutes whenever started, until there were sufficient numbers in different provinces to form their own Provincial Federations – temporary, until they again could be subdivided. Because of their great distance away, the Auckland Institutes, then only four in number, formed the second federation. There followed very shortly the Wellington Provincial Federation. The movement rapidly extended to the South Island until in due course the organisation was structurally completed by the formation of the Dominion Federation.

The detailed story of those early days can never be fully told. Like the pioneer settlers, one was too busy breaking in new ground, building and cultivating, to keep a record, and the notes on memory’s tablets have become indistinct in places. One looks back over long and usually solitary

FOREWORD xi

journeys, mostly in a trusty little car, on highways or rough side roads covering country from Southland to Dargaville, and totally many thousands of miles. one’s recollections are of wonderful hospitality and kindness in many a modest home, and of moving stories of the family’s early struggles, of plans and hopes for the younger generation, of sacrifices for their education and advancement, of sly fun from the man of the house, easily understood as indicating keen interest in this new countrywomen’s movement, and often quiet pride in “the wife’s” newly found talent for public speaking or for leadership. There was the thrill of discovering for oneself the “Nova Scotians” at Waipu, the delightful picnic meeting near Murchison, with panning for gold going on in the nearby stream, and the members wearing ornaments of the gold they themselves had washed out. A hundred other scenes come to mind.

The Women’s Institute Journal, New Zealand Home and Country, had an even more unpretentious beginning than the Institutes themselves. The need for a means of disseminating information and of combating the limitations of self-satisfaction and isolation early became apparent. While common funds were still lacking to provide a better means, I sent out, for a short time, a quarterly manuscript letter, of which a copy of two may still be extant. A little later the editor of The New Zealand Farmer became interested in the movement and offered generous space in the Women’s section of his journal. Advantage was gratefully taken of this, but soon our friend realised that The Farmer’s subscription might be an obstacle to many Women’s Institutes members, and he allowed us separate reprints of our news after it had appeared in his pages. Thus, it may be said, Home and Country first came into

xii TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

being. In a little while it developed to the point of acquiring a separate independent existence.

Other aspects of these pioneer days of the Women’s Institutes in New Zealand must await the future historian. Through all there runs a thread of gold, the single-hearted devotion to the cause, and the loyal co-operation of the great majority of the women of all types who emerged to take leading parts in the developing organisation. It is tempting here to mention names, but all or none must be given, and lack of space compels these, too, to be left for the pages of a history.

In this rapidly changing world the “visibility is poor.” One thing alone seems reasonably sure, that so long as the organisation preserves its ideals and its original free democratic principles it will maintain its remarkable vitality; and furthermore, it will continue to render the Dominion valuable service as a training ground in the understanding and practice of those same principles so essential to the preservation of freedom and peace in the world to-day.

Omatua,

Rissington.

June 2nd, 1939.

Foreword

By Amy G. Kane, Dominion President, New Zealand Women’s Institutes

In the year 1940 we in New Zealand will celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the founding of our country as a British possession; first as a colony, later as a self-governing dominion.

Each year gatherings of the early settlers celebrate the founding of their province and pay honour to our early pioneers, but the ranks of these are fast diminishing and already memories of the first struggles in a new and strange land are growing hazy.

To preserve these memories of our parents and grandparents, and in some cases great-grandparents, the Dominion Federation of Women’s Institutes has for several years held competitions for pioneer tales, and so many and varied have these been, that they have seemed worthy of publication – hence this book which the Women’s Institutes have produced in grateful remembrance of those women, who helped their men-folk to build up this new dominion of our great Empire.

And while we pay tribute to the women of the past, let us not forget the women of the present. Ours is still a young country, still largely an agricultural and pastoral country – many of our pastures hewn out of the bush; and in some cases our women in the backblocks are still struggling with primitive conditions in order to produce the butter, cheese, and mutton, that are their staple means of livelihood. A few women still have to ride many miles over rough tracks in order to reach their homes, and in some cases during a dry spell, water still has to be carried

xiii

xiv TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

for the washing that is done in an outside boiler. Wood has to be chopped for the cooking stove, and many women milk a number of cows besides attending to their housework. In many homes during the evenings, the children do their lessons by the light of kerosene lamps, while father reads the paper, possibly a week old, since distances are long and mails few; and mother does the sewing for the family, perhaps to the strains of music, for wireless has done something to bring the most isolated homes of New Zealand into touch with the outside world.

These are the women who run some of our more distant rural institutes, sometimes travelling many miles to their meetings, over roads deep in mud in the winter time; who help to bring the interest of “Institute” into the lives of our Maori sisters; who find time, also, for public work, and who, no less than the women of the past, are always ready to give a helping hand to a neighbour in time of need.

While many country homes have the benefits of good roads, hot-water supply, electricity, and other amenities, let us not forget those women who are still “pioneering” our country, bringing more and more of our land under cultivation; and let us do honour to them in honouring our first pioneers in this Centennial year.

And so, for the benefit of future generations and in memory of our mothers who helped to make this country a happy habitation for us, we offer you this book and hope that it will find favour in your eyes.

Editor’s Note

This is not a history book, nor is it a collection of short biographies of the most outstanding women of our country; rather is it a book of simple tales, chiefly memories that have been handed down to us by our mothers and grandmothers. The tales tell chiefly of women, but the lives of our grandfathers and grandmothers were so closely bound together that to tell of one without the other would not give a true picture of the pioneering days.

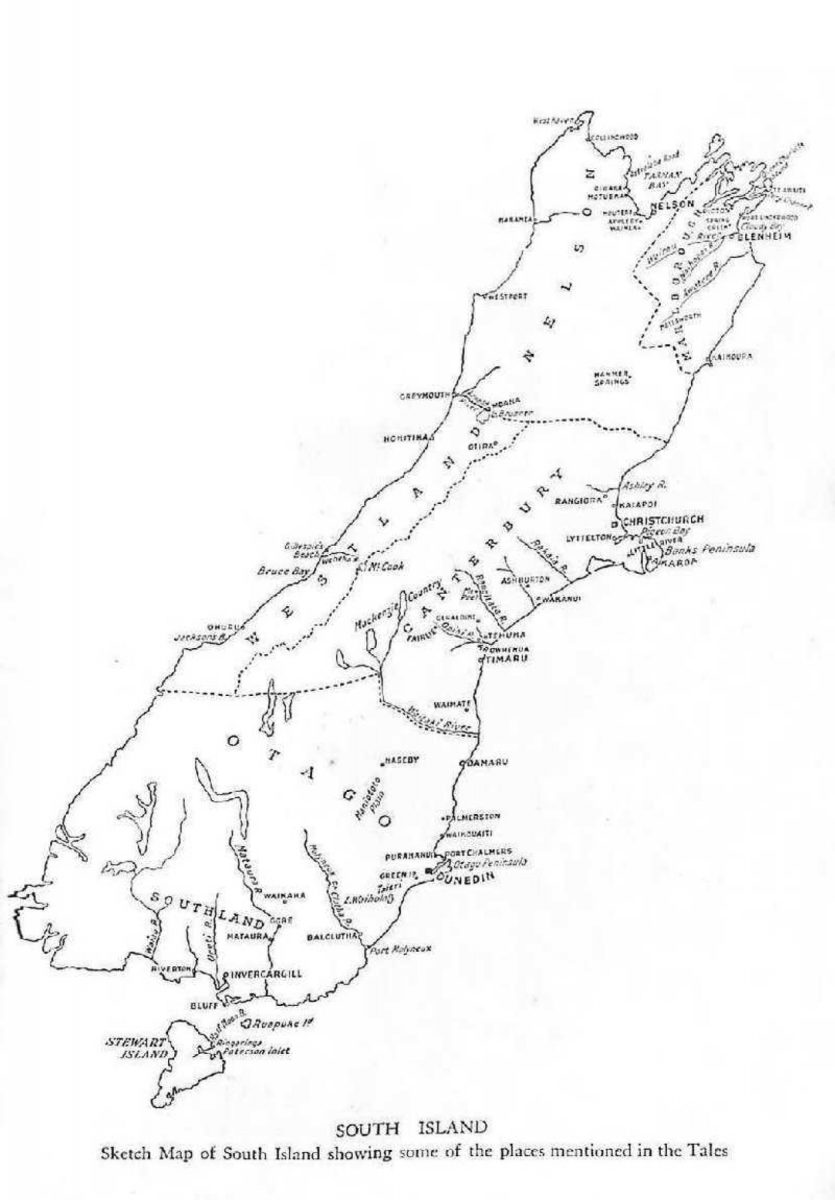

We have tried to make the book representative of every district in New Zealand, but have not been entirely successful, because although some federations have sent several tales of high merit, others have sent nothing at all. We have tried, also, to depict every phase of woman’s part in pioneering. There are stories of the wives of missionaries, miners, storekeepers, schoolteachers, farmers, runholders, accommodation-house-keepers, and numerous others. But although these women have travelled along many different paths of life, a great sameness is noticeable in the tales they have told. They have told of “Maori scares,” when they had to flee for their lives from hostile natives, and of other “Maori scares” which proved to be merely neighbourly visits from friendly tribes; they have told of their first efforts to cook with a camp oven; loneliness; long walks, rough drives in bullock drays, and long rides by women who were quite unused to horses; babies born with no help other than that given by a kindly, though possibly inexperienced, neighbour; friendships never broken; and the wonderful joy of letters from Home (always spelt with a capital H), letters written on thin “foreign” paper, the fine writing crossing the pages,

xv

xvi TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

not only once, but sometimes thrice, in an effort to avoid excess postage.

These tales have not been written by professional authors, but by the children and grandchildren of pioneers, sometimes even by pioneers themselves; probably few of them have ever tried to write a story before. Two or three of these tales have been published elsewhere. When I have been informed of this fact, I have acknowledged it, but it is possible that some have been previously published without my being aware of it. If this has occurred, I ask the forgiveness of the persons concerned for my unwitting breach of etiquette.

The tales cover a considerable span of years; from the earliest days of settlement down to comparatively modern times. A pioneer is “one who goes before, as into the wilderness, preparing the way for others to follow,” and to-day women are still preparing a way for those who will follow after them.

I regret that the necessity of keeping the price of the book within the means of every W.I. member, has made it impossible to publish all the interesting tales that have been contributed by members throughout the country, but those not included in this book will be preserved in some place where they will be available to students of local history. It has been necessary, also, to shorten many of the tales, and to eliminate nearly every individual tribute. The whole book is a tribute to our pioneer women, and

I hope that the collection and preservation of these memories will do something to show the gratitude of the present generation to its mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers, who went before and prepared the way.

June 8th, 1939.

A. E. Woodhouse,

Blue Cliffs Station,

Timaru.

Acknowledgements

In order that the facts recorded in this book might be as accurate as possible, for human memory is very fallible, each of the nine parts has been submitted to the appropriate Provincial Centennial Historical Committee. The thanks of the Dominion Federation are due to the members of these committees for their careful work in checking the tales and correcting any historical inaccuracies, thereby increasing considerably the value of the book.

The Federation is grateful, also, to the many other persons who have assisted in the compilation of this book. In particular I should like to mention the staff of the Alexander Turnbull Library, to whom I have frequently appealed, and never in vain, for information; the authorities of the Canterbury Pilgrims’ Association, Christchurch; of the Hocken Library, Dunedin, and of the Otago Early Settlers’ Museum, Dunedin, who gave permission to make and publish copies of letters, journals, pictures, and photographs; to Margaret Cassie of the Blue Cliffs W.I. who assisted with the correction of proofs; and to Niall Alexander who has given much helpful criticism.

xvii

Contents

Page

[…]

II. Hawkes Bay

12. Danger from Te Kooti. By F. B. Gibson, Matawai W.I. 44

13. Old Waikari. By Willina Mackenzie, Putorino W.I. 46

14. Frances Bee. By Willina Mackenzie, Putorino W.I. 55

15. History of Petane. By D. Nicholls, Bay View W.I. 60

16. Omatua. By Amy H. Hutchinson, Rissington W.I. 65

17. Rissington. By Geraldine Absolom, Rissington W.I. 66

18. The Story of John and Mary Hameling. By M. Moriarty, Ohinewai W.I. 68

19. History of the Waikopiro Block. By members of Waikopiro W.I. 72

xxi

44 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

II. Hawkes Bay

12. DANGER FROM TE KOOTI*

By F. B. Gibson, Matawai W.I.

In the sixties, my people had a farm named Kairiki and a store near Te Arai (now Manutuke).

On one occasion my father, Mr. W. S. Greene, had to go to Napier for several days, and, as there had been many Maori scares, my mother did not dare to remain at her home without him, so with her three children she went to stay with her sister, Mrs. Skipworth, who lived at Makaraka, about seven miles away.

On November 9th, 1868, my mother decided to ride over to Kairiki to see that everything was well there. She left her children in charge of her sister and set out on horseback. She arrived without seeing any sign of trouble, but while she was looking through the place, some friendly natives, who had swum the river in order to warn the pakehas, rushed up and told them all to fly for their lives, for Te Kooti and his followers had landed on the beach at Whareongaonga, and were making that way. The men who were working on the farm quickly saddled horses; my mother took £20 from the till, put it in her pocket, and away they tore with other white settlers and some friendly natives, both men and women.

They made for the Muriwai Beach, and travelling as fast as they could along the beach they reached the bush in safety;

*The scene of this tale is laid in the Auckland Province, although it is in the Hawkes Bay Land District. I have included the tale in the Hawkes Bay section of the book because it seems to belong there.

HAWKES BAY 45

and there they spent the night, not daring to light a fire. As soon as it was light next morning they continued their way to the Mahia Peninsula. There they were picked up by a small scow and taken to Napier, where they stayed for a short time before being taken back to Gisborne by boat.

In the meantime my uncle and aunt at Makaraka had heard of the approach of the hostile natives. They gathered up as many as possible of their most valued possessions, and with my mother’s children as well as their own, packed into their boat and made off down the Taruheru River to Gisborne, where they arrived without mishap, although the boat was so heavily laden that, in order to lighten her, my eldest cousin and my brother had to take turns in running along the bank.

On that same day, November 10th, some militiamen and settlers around Matawhero (situated between Makaraka and Manutuke) were surprised and murdered by Te Kooti and his men, and their homes burnt to the ground. The names of those who were murdered on that fatal day are preserved on a stone in a large enclosure in the old Makaraka cemetery, which is only four miles out from Gisborne on the Main North Road.

I often think of the agony of mind that my mother and her sister and the other settlers’ wives must have suffered, and how terrified they must have been when the time came to go back to their homes, in many cases burnt to the ground, and start again. They were told that all danger was now over; but how could they be sure that what had happened in the past would not happen again in the future?

46 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

13. OLD WAIKARI*

By Willina Mackenzie, Putorino W.I.

The coastal district of Waikari, situated half way between Napier and Wairoa, has had a romantic history; and a stern fight was fought there by the early settlers to subdue the wilderness.

Less than 100 years ago these hills and valleys were the home of the Ngatipahuwera – the tribe of the burnt beard; on the big hill, Pukepiripiri – bidi bidi hill – are signs of a big encampment of bygone days, and here have been found many Maori weapons. At the mouth of the Waikari River was once the big pa of Te Kuta, from which the inhabitants have long since drifted away, the last remaining one being old Rewi Te Whanga, whom I knew when I was a child, and remember as a typical old-time Maori, a natural aristocrat.

The first pakeha settlement at Waikari took place about a hundred years ago. The beach, in common with many others along the coast, was used by whalers, among whom were several half-cast Tasmanian blacks. Wild tales are told of their terrible deeds, and their lawlessness and low morality did much to debauch the Maoris with whom they came in contact. To such men as these whalers were Maori maidens bartered, often for a cask of rum.

The hill, Te Whanui, 1,200 feet above sea level, was the whalers’ Look-Out, whence they were able to see several miles

*The name is composed of the Maori words wai water, and kari to dig. The Maoris say that when they used to come to Waikari in the summer time, they found it impossible to drink the water because salt water came such a long way up the river. One day a dog dug a hole near the river bank which filled with fresh water, and the problem was solved.

HAWKES BAY 47

out to sea. Many of the old iron try-pots in which they boiled down the blubber are still to be seen on the beach.

Mr. W. Thompson was stationed at Waikari as trader for Mr. Alexander of Napier, which town was then in its infancy. In the year 1847 his house took fire and his wife and children were burnt to death. For a long time some Maoris who had been refused payment for some undelivered pigs were wrongly blamed for this tragedy.

In the early days white settlers were few and far between, and holdings of necessity covered huge areas.

The first mob of sheep to be driven up the coast track was in charge of Mr. A. Reeves, of Poverty Bay, whose son is one of the present day settlers in our district. A gang of Maoris was sent ahead to cut a narrow track through the scrub. The sheep in those days were all Merinos and the cattle were Long Horns, huge stringy beasts, yellow and white in colour. The Merinos have now given way to Romneys, and the cattle nowadays are Polled Angus and Herefords, but traces of the earlier breeds may still be seen.

Amongst the early settlers of the district were the Hardings, who had about 20,000 acres; the Anderson family, who had a vast holding from Pukepiripiri (the present Glen-brook), Kakariki, and down to the Mohaka River; the Wilkie family, early owners of Waikari Station; and Mr. James Tait, father of Mr. John Tait, the present owner of Waikari Station.

Mr. James Tait came up the coast with his young family in 1867. John remembers several Hau Hau scares when the settlers fled for their lives. One shearing time, the friendly Maori boys came running round the beach crying that Te Kooti was coming. Shearing at once ceased, the half shorn sheep were bundled out of the shed pell mell, with the loose wool ripped off. The shed was barricaded and pakeha and friendly Maori alike waited in fear for the dreaded Te Kooti. It proved to be a false alarm; but some weeks later,

48 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

on April 10th, 1869, the black and white Hau Hau flags appeared at Mohaka and the terrible massacre took place, only a few miles from Waikari. It can never be forgotten that the palisaded pas of Mohaka were defended by its womenfolk with only a handful of old men and the gallant Rowley Hill, against 300 yelling demons. When the relief party arrived from Napier, four days late, and the Ngatipa-hau-wera warriors returned from an expedition to Waikaremoana, Te Kooti had retreated to the Urewera, and all they could do was to bury their dead.

The Taits and the few other white settlers, including the Finlaysons, who had started an accommodation house at Te Kuta on the coast track, had fled to Napier. John Tait, then a small boy, remembers meeting the soldiers coming along Tangoio beach dragging two big guns. They had halted the previous night at Finlayson’s deserted accommodation house, carousing and dressing up in the women’s clothes. Mr. Finlayson’s usual custom was to hide the liquor in a nearby cave, but in his hurried flight this had not been done. For some years the disordered scene was laid, unjustly, at the door of the Hau Haus. Going along the beach the soldiers met J. Sim with his wife and young family, who had hidden in the bush for days, one child dying of starvation.

Te Kooti fell back to the mountainous country of the interior and the settlers returned to their homes.

The following year Mr. James Tait was drowned on the Wairoa beach while carrying despatches, and his wife and children were left to carry on under great difficulties. Often running out of stores, and with very little money, but with boundless courage, they at times had to exist on what they grew, even being without tea and many other things that we now consider to be amongst the necessaries of life.

Until well into the present century there was not a house between Waikari and the beautiful Lake Tutira. Waikari owed its existence as a village to the proximity of large

HAWKES BAY 49

grazing runs, including Putorino, Glenbrook, and Pekapeka, the last being now included in Moeangiangi, “the Valley of Watchful Sleep.”

The first owners of Putorino Station, from which this district takes its name, were Messrs. Brandon and Bruce, but the history of this huge grazing run is indissolubly linked with the name of Mr. George Bee, who owned it three times. The run was held for a time also by Mr. Herbert Guthrie-Smith, of the adjoining station, Tutira, and author of Tutira – the Story of a New Zealand Sheep Station, and several classic books about birds. In his early years George Bee lived at Maungaharuru. There was, at that time, an ever-present fear of Maori risings, and he always slept with a revolver under his pillow. When word came of the Mohaka massacre he joined the soldiers on the coast. One day they found the bodies of Mr. and Mrs. Lavin, lying in each other’s arms near their lonely homestead, and the bodies of their little boys lying where the tomahawks had struck them down. One of the soldiers tried to cut the rings off Mrs. Lavin s fingers, and Bee told him that if he did so, he would shoot him. The slow methods of the soldiers disgusted Bee; they progressed only about 10 miles a day, and finally the pursuit was abandoned.

In the early nineties a narrow track was made through the Matahourua Gorge by which the settlers could travel to Napier. A hostelry was opened at the junction of the coastal and the Napier-Wairoa roads, and Mr. Alick Knox, the pioneer publican, who was also a celebrated horseman, started business under canvas until a building could be erected. The formality of securing a licence was dispensed with, but thirsts were quenched nevertheless, and accommodation of a sort was available to travellers. Old identities tell of the wild fights and carousals that left no doubt as to the potency of the liquor provided, and they remember seeing every window broken and boarded up after a visit from roystering bushmen.

50 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

The packmen who carried the mails over the primitive tracks had a very difficult job, but they looked on dangers as being all in the day’s work, which they carried out with a high sense of duty. They fought their way through the bush in all weathers, swam Hooded rivers, and more than one lost his life in an effort to deliver the mails and keep faith with the lonely settlers for whom they were almost the only link with the outer world.

Later a rough road was formed. Waggon teams took the place of the pack-horses, and in the nineties Mr. Mclntyre started the first coaching service between Napier and Wairoa. The long trying journey was made twice a week by the great lumbering coaches, drawn by five good horses, which forded flooded rivers, struggled over roads often axle-deep in mud, and negotiated hairpin bends with a steep drop of hundreds of feet below the narrow road, where any slip would probably have meant death. The journey from Napier to Wairoa took the best part of a day, and the passengers eagerly looked forward to the stop at Sandy Creek, where refreshments in the shape of thick bread and butter and a cup of tea with condensed milk were most welcome. Fresh horses were yoked in, the tired ones led away to the stables, and the spanking team, swinging along at a fast pace, was soon in Waikari. It was a great moment when they came swinging down the hill and pulled up near the little knot of eager, waiting people, for the arrival of the coach was the most important event of the week to the little township. On one occasion the driver pulled his team up with such a flourish that the coach overturned, but none of the passengers was hurt. Accidents were very rare, however, for the coach- men were past-masters with the reins.

When the mail was unloaded it was taken into the hotel, where it was sorted, and for many years the Royal Mail was handed out over the bar to men and women alike.

At this time the township of Waikari consisted of the

HAWKES BAY 51

hotel, the coaching stables, the blacksmith’s shop owned by Mr. Begley, and the store. Behind the store was a room known as the Dance Hall, the seats round its walls were formed of planks resting on packing cases, and the walls were ornamented with sides of bacon, etc.

Many years ago, my father, Kenneth Mackenzie, bought the Glenbrook Station, 6000 acres of bush and scrub. There are few districts where a more constant battle has been waged against the ever-springing manuka, which in early days was practically impenetrable. Some parts of the run were “tapu” and here no Maori would cut the scrub. An earlier owner of the station was Mr. William Gilmour, a hardy Ulsterman, who made the first tracks, scoured his own wool, and made bricks with which he built his own chimneys.

Station life a few years back was surely the best in New Zealand, and perhaps it still is, though conditions have changed. As children we looked forward from one shearing’s end to the beginning of the next, when the gang of twenty or so Maori men, women, and children, with the inevitable kuri* and up to forty horses, would come stringing into the station. They were busy, happy days when at every stop the shed was filled with the sound of laughter and sweet singing, and the sight of a spirited haka or poi dance. For some years my father and the Messrs Tait shipped their wool from the Waikari beach, a slow and dangerous task; later it was taken to Napier by a six-horse waggon team, which returned bringing a six-months’ supply of stores. The whole trip took six days.

The road to Napier was still very poor, and was unmetalled, with few bridges across the rivers. It was a great day when it was sufficiently improved to allow the first car to pass through on its way to Wairoa along the route now traversed several times daily by luxurious service cars. “The old order changeth, giving place to new.”

* Dog.

52 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

About the year 1918 Putorino Station was purchased by the Government from Mr. George Bee and cut up into about fourteen sections for a soldiers’ settlement. Now began a new era in our district: where formerly there were less than a dozen families to-day there are dozens.

Green pastures have taken the place of the wilderness of fern and scrub, and plantations now shelter almost every little homestead. The plough has changed the face of the country, and where one might once have ridden for days without seeing a sign of human life, now on all sides is evidence of progress and endeavour. Land that was once despised is now considered to be good dairying country and the East Coast Railway now runs right through our district and has reached Waikari.

But although the district of Waikari is now comparatively closely settled, there lies behind it a wide area on the borders of the Urewera country that is still in the pioneering stage, and until a few years ago could be reached only by a pack-track over which the few settlers packed out their wool and returned bringing, probably, a year’s supply of stores. Now a road has been formed which branches off the Napier-Wairoa highway near Lake Tutira and leads inland, at first through low-lying ridges with a few scattered farms, then through forlorn and practically uninhabited country as it climbs the steep range; then through a mile of wonderful bush at the end of which one comes suddenly on the home of a settler built in a little glade. By the side of the road some humorist has placed a notice “Speed Limit – 10 miles a month.”

The top of the range is reached, and now one may follow the narrow twisting road for many miles without sign of human habitation as it winds down to the valley where the Mohaka and Te Hoe rivers join – the end of the road. About a mile away, dominating the landscape, is a peculiarly black and forbidding looking hill known as “Te Kooti’s

HAWKES BAY 53

Look-Out,” where the remains of walls and palisades can still be seen. Its steep, rocky sides and narrow top, where there is a tiny spring of water, made an excellent fortress in days gone by. In this valley is the home of a Maori family, who are native to this place. Shy children scamper away at the sight of strangers, and fascinated, we watch the older members of this family swimming their horses across the fierce rushing river, pulling behind them heavy planks of timber which leave a line of white, crested foam in their wake.

A mile or so across the Mahoe river is the lonely home of a white settler, Mr. Roy Andrews, and his family, the pioneers of this wilderness. This man, coming into the valley in his young days, saw the “country beyond” across the river, and literally cut his way in with a slasher. He took up some thousands of acres; materials and furniture for a home were packed in over the scrub covered hills, and he built his home with his own hands. It is hard to believe that only 20 miles away as the crow flies from this lonely little homestead are lighted streets, smooth roads, and the forty-hour week. One day her young son found Mrs. Andrews dead in her bed – and there were no other human beings within eight miles. From the home runs a rough track down which her body was sledged for two miles, and then transported across the river in a cage. And this was only last year! Together in life, husband and wife were not long apart – three short weeks divided their passing.

Some miles beyond “Te Kooti’s Look-Out” is another lonely station home set in between the steep hills, and to be reached only by a rough bridle track. Here a complete change of landscape occurred during the great earthquake of 1931. Huge landslides fell into the Te Hoe river, damming it entirely, and a large lake was formed where once stood the homestead, that had been saved by sawing

54 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

the house off its piles and floating it away. The site of the homestead with its outbuildings and trees was completely submerged for seven years. Then the recent heavy floods broke the dammed outlet of the drowned valley of Te Hoe; thousands of tons of water were liberated; a surging wall with breakers 50 feet high roared down the river to the far-off coast, sweeping all bridges and bushmen’s camps before it, and causing enormous landslides. The woman who had seen her homestead site, with its trees and garden, swallowed as she thought for ever, now saw revealed the ghostly bare trees, and the skeleton remains of buildings, amid thousands of dying fish.

It is thought that the 1931 ‘quake had its centre on the Waikari coast. On Mr. John Tait’s property a huge upheaval swept more than 100 acres of land far out to sea. Sheep and cattle were engulfed; further along the coast about 150 acres fell from the towering Moeangiangi Cliffs and completely changed the coastline. Near the mouth of the Waikari River a hillside burst open and collapsed into the river, causing it to sweep over Mr. James Tait’s home then situated high on the flats above; on the other side of the river Mr. John Tait’s woolshed and thousands of pounds’ worth of machinery, were swept away. The river mouth was completely blocked for half a mile and an opening had to be dug with spades.

The earthquake wrecked roads and railways, and for some time we were as completely cut off from civilisation as our fathers had been before us. But “Carry on,” was the watchword, and life soon became normal once more.

Now the whistle of the train as it rushes past, and the roar of a ‘plane overhead link us to the outer world, and sever our thoughts from the not so far distant pioneering days. Should we recall those days? I say, Yes! that young people of to-day, and those yet unborn, may know what their forbears had to contend with, and honour their memory.

HAWKES BAY 55

Picture our first settler, as, standing on the great coastal hill, Te Whanui, he gazes over almost the whole of Hawkes Bay, mile upon mile of dark serried hills. His world to conquer! So he shoulders his pack, and, moving on, is lost to our sight. We are sure that he, and those of his kind, played their part well.

May we be worthy to follow in their footsteps, and take up life’s battle with some of their high endeavour!

14. FRANCES BEE (MRS. DAVID ROSS, OF WILLOW FLAT)

By Willina Mackenzie, Putorino W.I

Ninety-eight years ago, in the year 1840, Mr. Frank Bee and his young wife arrived in Wellington in one of the first three immigrant ships to come to New Zealand. Mr. Bee later took up a block of native land in Waimarama where several children were born, including a son, George, and a daughter, Frances.

Some years later the family acquired land near the wild Maungaharuru Range, inland from Mohaka, a district rich in Maori legend where many remains of old fortifications are still to be seen. The children learned that the name of the great hill nearby, “Patu Wahine” (Killed Woman), came from the old tale of a Maori warrior who threw his wife over the cliff; and that many other landmarks took their names from deeds of violence of bygone days.

When word came that Te Kooti had escaped from the Chatham Islands, Frances Bee and her young sister were

56 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

quite alone in the wild solitude of Maungaharuru, their brother being away on the coast getting stores. When night came on the girls crouched in terror in the slab whare. Every rustling bush caused them to start, and in every shadow they saw the dark form of a Hau Hau warrior, for this was the Te Kooti Trail! However, at that time Te Kooti was far away, and it was not until some time later that his warriors swept past and burned the whare where the girls had spent their night of fear.

Frances Bee later met and married young David Ross, who, not long from school in Lyttelton, had joined the constabulary in Napier and had come up the coast with the mounted forces at the time of the Mohaka massacre. They took up land at Mohaka, where they lived for some years, and Mrs. Ross, though quite a young girl, gained considerable prestige with the Maoris, who grew to rely on her calm judgment and often came to her as a peace-maker. On one occasion she was asked to mediate between a husband and wife – the wife had chopped her husband’s ear half off with an axe because he had hit her. Mrs. Ross’s verdict was, “Serve him right! He should not have thrashed his wife.” One Maori woman went mad, and ran about the pa flourishing an axe. Again the Pakeha wahine was sent for. The demented Maori rushed at her, but Mrs. Ross laughed kindly, and the poor woman threw the axe away and wept on her shoulder. Afterwards she was sent to a mental hospital.

At one time two Maoris were partners in a flock of ewes, the agreement being that each man should pay half the cost of the necessary rams. One paid, but the other did not. The owner of the rams declared that all the lambs were his, and a heated argument arose that might have ended in bloodshed had they not appealed to Mrs. Ross.

HAWKES BAY 57

The man who had paid for the rams claimed all the lambs.

“No lambs if no rams,” said he.

“No lambs if no mothers,” replied Mrs. Ross.

Considerable discussion followed, and finally Mrs. Ross gave her decision:

“The lambs are to be divided, provided that each man pays his share of the rams.”

Later, Mr. and Mrs. Ross lived for a time in the Moengi Valley, where Mr. Ross managed a property. They were there when the now pardoned Te Kooti came down the coast with about forty of his wild followers. Mrs. Ross was alone in the house when they appeared in the valley – and such a lonely valley – set in between giant hills, the sea close by, the nearest road thirty miles distant, and no other human being for many miles. She crept into the bush, but seeing the Maoris moving peaceably about, she ventured forth again, gave them vegetables and milk, and they stayed talking with her for some time.

In the beginning of this century Mr. Ross decided to take up 11,000 acres of unoccupied Maori land in the back country between Waikari and Mohaka. which he had previously explored while on camping trips with his boys. On the one flat situated by the swift rushing Mohaka river they found a solitary willow tree, surrounded by native bush. Perhaps years ago a Maori had stuck a twig in the ground; it had grown and flourished, and now gave the name Willow Flat to the new station.

Willow Flat could be reached only by following rough pig tracks over bush-covered hills for 20 miles after leaving the Napier-Wairoa road. It was no light undertaking for people no longer young to start life anew in such an isolated place.

For some time the family lived in tents; later slab whares with rough earth floors were built by Mr. Ross and the

58 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

boys. Cooking was done in an open fireplace and bread baked in a camp oven.

During the first winter at Willow Flat the father and his two sons killed 800 wild pigs, which were a menace to the young lambs in the spring, and increased very rapidly unless kept in check. Bush-felling and packing were done by Maori contractors, who only in later years seem to have taken to shepherding. The flock had to be driven out to Mohaka to be shorn. The first year’s clip was sold at only 3d a pound; the cheque was nearly all swallowed up in shipping expenses and there was barely enough left to pay the grocer’s bill. Times were hard, then.

The intense loneliness when the men were away with the sheep, at times oppressed Mrs. Ross, left alone with her little girls, and often they climbed far up the hills hoping only to see smoke in the distance. Yes, there it was, miles away – and they returned comforted; there were others in this empty land besides themselves.

They lived very much in a world of their own. Communication with the outside world was difficult, and there was wild excitement when a visitor arrived – particularly if he brought a pack horse carrying the mail. There would be a rush to daub fresh mud in the holes in the clay floor, and a squabble amongst the female members of the family as to who should wear the best cardigan; at one time there was only one pair of shoes amongst them all.

Clothing sometimes became scarce, because Mrs. Ross went to Napier only once a year, or even less often, for the 60-mile journey was not without hazards, even after the road was reached. On one return journey, the coach capsized at a dangerous corner; all the passengers were thrown clear except Mrs. Ross and another, and the coach with them inside it, rolled down the hill and turned over three times before it was stopped by a tree. Mrs. Ross put her hand through the window and was pulled out, not seriously

HAWKES BAY 59

hurt, though badly shaken. She and the other passengers then walked for several miles, after which she had the usual 20-mile ride home across the hills to Willow Flat.

Many years passed before a road into Willow Flat was begun, and although the road progressed very slowly, it was completed at last, thirty years after Mr. and Mrs. Ross had taken up the station. Long before the road reached Willow Flat a house had been built under the lee of a high rock cliff facing the Mohaka river. It is now surrounded by an orchard, and a bright garden full of flowers blooms round it.

Mr. Ross and the owners of several distant stations joined in erecting 30 miles of telephone line, each place cutting its own poles and packing poles and wire across the gullies. What a thrill for the Ross family, father, mother, brothers, and sisters, all eagerly awaiting their turn to hold the receiver and shout “Are you there?” and to hear a voice reply from what must have seemed another world!

The loss of two sons, one from illness, and the other killed in the Great War, was a deep grief to the parents, then getting old.

Mr. Ross passed on in 1938, in his 86th year. His wife is still with us – a tall, gracious, dignified old lady, now in her 83rd year, whose flashes of kindly humour and keen interest in everything around her, show that the long years of loneliness and hardship have not quenched the gay, laughing spirit of the girl, Frances Bee, who married young David Ross, and at his side, with indomitable courage and resource, helped to build a home in the wilderness.

60 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

15. THE HISTORY OF PETANE*

By D. Nicholls, Bay View W.I.

The Maoris called the place Kai-arero for this reason:

A war party from the Urewera country led by the Chief Te Mautaranui (the bearer of a large spear) invaded the district and eventually camped on the shore of Lake Tutira opposite the small island of Turanga a kaou (standing place of the shag). Here the local people with their chief, Tiwaewae, had taken refuge. After some time, as the raiders would not go, Tiwaewae decided, against the advice of his wise men, to go ashore in his canoe and try to make peace with them. But as soon as he landed he was seized and killed, his body opened up, dressed, and hung at the entrance to the valley where all his friends could see it; eventually it was eaten. Later a war-party set out to avenge Tiwaewae’s death; Te Mautaranui was overtaken and slain; he was then roasted, the dripping carefully collected, his tongue cut out and packed in a calabash with the dripping, the whole covered with the tattooed skin from his buttocks, and sent back to Tiwaewae’s tribe. Thus the tongue that ate Tiwaewae was itself eaten by his kinsmen, and his death suitably avenged.

The home of Tiwaewae was therefore called “Kai-arero” the “Eating of the Tongue.”

When the missionaries came to Kai-arero they changed the name to Petane, which was the Maori way of pronouncing Bethany, but later the Government changed it back to Kai-arero. Then some misguided persons agitated for the name to be changed once more; the place was given the inappropriate name of Bay View, and dispossessed of

* Petane and Petane Valley included what is now called Eskdale until about 1900.

HAWKES BAY 61

the historical name Kai-arero. To many of the older settlers, however, it still remains Petane.

The first white settlers came to Petane in 1850 and 1855 – Mr. and Mrs. J. B. McKain with their family of small children, and McKain’s two brothers with their wives and families, Mr. and Mrs. Torr, Mr. and Mrs. McCarthy, and Mr. and Mrs. Villers, all with young families. They took up sections of land, about 100 acres for each family, for which they paid 5/- an acre or thereabouts, and built huts of clay, rushes, and raupo, which they used as homes for a considerable time. The first wooden building was a small one with a gable at each end which stood somewhere near where Mr. Henderson Wilson now lives. There were no roads, and the settlers, who arrived in increasing numbers, had a very unpleasant trudge over the beach, sinking ankle deep in the soft sand and shingle, when they walked to Napier for fresh supplies of stores which they carried home on their backs. Therefore, whenever possible, transit was by row-boat through the Inner Harbour to the mouth of the Wai-o-hinganga river. As this was too narrow for oars to be used, men walked along the bank, pulling the boat as far upstream as possible by means of a rope. Thence the journey was continued in bullock or horse sledge, generally the former, for horses were very scarce. It was not until about 1860 that a road of sorts was formed.

Fowls were procured from Rev. W. Colenso, cattle and sheep were accumulated, and with seeds of vegetables sent from Home, the settlers soon had gardens and crops under way, though the ground was worked chiefly with no better implements than spades and forks. Butter and eggs were taken to market in the little town of Napier, packed in bags thrown over a horse’s shoulders, or if no horse was available, they were carried by hand. The wheat was cut with reaping hooks and scythes, threshed with flails, and winnowed by hand through riddles or sieves,

62 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

both women and children helping with this work. One of the settlers had a small hand-mill in which some of the wheat was ground, but the majority of it was sent by boat to Napier to be ground into flour.

Some time in the seventies Mr. Torr began to trade up the river in a tiny steamboat, the landing stage being just in front of Mr. Villers’s accommodation house. The river-bed was much nearer to the hills than it is to-day, and there was deep water under the cliffs by the present hall.

About 1860 it was found necessary to build a school; more and more settlers were arriving with their families, who had to be taught the three “R’s,” which was about all that was considered necessary in those days. Mr. Loisel taught in the school for a number of years, and after he left, sometimes there was a master and sometimes there was not. The Rev. W. Colenso undertook the responsibility of putting the children through their examinations; he would cross by the ferry between Port Ahuriri and Westshore, walk five miles along the beach and three more inland to the school, examine the children’s lessons, and walk home again to Napier, very often without waiting to have any refreshment.

The Australian blue gums which are still growing in the school grounds, were planted by Mrs. J. B. McKain, who was responsible, also, for planting the first dozen or so of blackberry roots which she had obtained from Mr. Colenso, who, as a botanist, should have known better than to supply them; at times the pest has almost taken possession of the school reserve and the surrounding country.

Mrs. Craig, who lived a little way along the Taupo road, was the first to grow in her garden the beautiful evening primrose that now makes a golden glory of the Petane beach during early mornings and evenings in both spring and autumn.

HAWKES BAY 63

For many years the only musical instrument in the district was a tin whistle, owned and played by Mr. J. Stevens; it was in great demand for every social event; no wedding or christening was complete without it, and at dances his wife would stand at his side and wipe the perspiration from his brow as he played the various tunes.

Settlers came and went, and properties changed hands, for these were troubled times, and the white people lived daily in fear of Maori disturbances until 1866, when the natives were defeated at Omarunui and Petane.

A body of settlers had been camped in the Petane Valley for a considerable time, and on October 12th, Captain Fraser came with another body of men, collected those already in camp, and moved further up the valley near Captain Carr’s homestead (now Mrs. Beattie’s). This was where Maori and Pakeha met, and the battle took place. The shooting was heard in the little homes in and round the Petane Valley, but thinking that it was merely firing practice, the settlers took little notice, until a soldier came riding down with orders that everyone, including women and children, should be taken up behind the firing lines for safety. By evening, however, the danger seemed to be over, and the settlers were allowed to return to their homes.

During the Te Kooti trouble in later years, the women and children were sent to Napier for safety, but dangers appear to have been taken very much for granted, for when speaking of them now, the old folk seem to consider that they were all in the day’s work, and not worth writing about.

As the years went by, the little township grew, and a number of new residents came to the district when the Te Pahou block of land was cut up for closer settlement in 1905. Good roads had been formed from Napier to Taupo and Wairoa, and between these places there were regular coaching services, which made their first change of horses

64 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

at Petane. About 1920 a motor service took the place of the coaches, and by 1923 there was a daily railway service as far as Eskdale in the Petane Valley.

On February 3rd, 1931, disaster, sudden and swift, came to the whole district. The day broke fine and warm, with no wind; but a very high sea had been running in the bay for several days from no apparent cause, and huge breakers washed up the beach at Petane and on to the railway line. At 10.45 in the morning came the earthquake. All buildings were damaged, many of them beyond repair; all communication was cut off; great landslides took place, and three of our residents were killed in Napier. It seemed that life came to a standstill around the Petane township; it was quite cut off from other districts, and it was many months before life settled down again even to anything approaching normality. Our beautiful little Waiohinganga river had completely dried up, or at least taken another course, and it now flows into the open sea instead of watering the flats round Petane on its way to the Inner Harbour; for this portion of the district had risen six or seven feet in the great upheaval. The railway line up the valley, over which was then running a daily service as far as Putorino, was converted into miles of twisted iron rails, and in many places completely buried under huge land slides. It remained in that condition for about five years before the Government decided to repair it and continue the construction of the uncompleted portion to Wairoa and Gisborne.

In 1931 a Women’s Institute was formed, and so we come to the present year, 1937, with our damaged homes long since restored, and life once again running smoothly and happily for the residents of Petane, or to give it the inappropriate name by which it is now known, “Bay View.”

HAWKES BAY 65

16. OMATUA

The Birthplace of Women’s Institutes in New Zealand.

By Amy H. Hutchinson, Rissington W.I.

Omatua is one of the oldest homesteads in Hawkes Bay, and to many thousands of women it is known as the birthplace and cradle of the New Zealand Women’s Institutes.

The station, which is divided from Rissington by the Mangaone River, a tributary of the Tutaekuri, first came into the light of history in the sixties, as a military grant made to Captain Anderson who worked it in conjunction with Captain Carter, who owned Waioaiti – probably the Wai-iti of to-day. Mrs. Anderson was the first Englishwoman to live in this district, and her daughter was born here in 1867.

The present house was built before the 1863 earthquake, and it still shows by roof curves, crooked walls, and undulating floors, the strain that it suffered on that occasion. During the earthquake of 1931, the house was much further shaken.

We have owned Omatua since 1907. The house had previously been used as an out-station for Apsley, but for some years it had been unoccupied by anything but bees, which we found in possession; honey was pouring down the stairs, and the house was overgrown with trees and creepers.

The severe flood of 1897, and the cloud-burst of 1924, when the river rose over 30 feet, made considerable changes in the lower garden, and the two main bridges were washed away. But the lack of bridges did not deter the members of the Rissington Women’s Institute from attending the meetings at Omatua, for they crossed the river by raft or in a box suspended from a cable, under real pioneer conditions.

66 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

17. RISSINGTON

By Geraldine Absolom, Rissington W.I.

Rissington Station has given its name to the district which now includes a number of sheep-runs of smaller acreage within a radius of about five miles.

An old settler says that Colonel Sir George Whitmore owned Rissington in 1858, but I found no record of this when I went to the Lands Office in Napier before their files were destroyed by the earthquake of 1931. I was able to note, however, that Crown Grants were given in this district to Captain Anderson in 1861, to Gray in 1862, and to Whitmore and McNeill in 1865.

Soon after his arrival in New Zealand, Colonel Whitmore bought out all the settlers from Rissington to Hukanui, and he owned land also in the vicinity of Poraite [Poraiti] in the Inner Harbour. This gave colour to his one-time boast that he owned land “from the Kawekas to the sea.” In all he had about 110,000 acres, and this he named Rissington after the estates adjoining his own home manor in Gloucestershire, which was unfortunately named “Slaughter.” It was obvious that he could not call this newly-acquired property in New Zealand after his old home when he was engaged in the Maori Wars! Whitmore was always trying to enlarge his holdings, and referred to owners of 15,000 to 20,000 acres as “only little cabbage gardeners.”

When the Colonel was stationed in Auckland in 1862 he wrote many letters to the manager, Mr. McNeill, in which he scolded him in approved military manner and gave him the most detailed advice. He sent stock (which included turkeys and rabbits) seeds, implements, and building material by schooner to Poraite, then by bullock drays through Puketapu to Rissington. He sent also a thousand gorse plants, which flourished and became a serious pest.

HAWKES BAY 67

The trees of many varieties which now beautify Rissington were brought from Australia and Tasmania; and Shorthorn and Hereford cattle and Lincoln sheep were imported from England.

At one time Colonel Whitmore was in command of a detachment of the Colonial Defence Force which was camped on a flat beyond the homestead, still known as Camp Flat. There were about 200 soldiers, and the B troop was in charge of Captain Anderson, of Omatua.

At the time of the HauHau rising word came to Rissington that there was to be a fight the next day at Omarunui. Two cadets – Nesfield and Hellyer – rode down to find out what was going on, and when they brought back word that the fight was over, they found that Major Green had assembled all hands and Mrs. Whitmore herself, on the terrace at the back of the house – all armed with rifles!

When Lady (then Mrs.) Whitmore first came to Rissington, she had to make the journey in a bullock dray. The bullocks were accustomed to loud swearing as a persuasion to pull harder, but on this occasion Colonel Whitmore took the precaution to impress upon the driver that he must on no account swear in the presence of the lady. When they reached the Mangaone the bullocks came to a full stop in the middle of the river. All permitted means failed to make them move, and Jock appealed to Mrs. Whitmore,

“Well, mum, it’s a case of stickin’ or swearin’.”

Not enjoying the prospect of remaining in the river indefinitely, she readily gave permission.

“Swear away, Jock.”

At the torrent of familiar words, the bullocks heaved and pulled the dray to dry land, and the journey was finished with no further difficulty.

In 1874 Robert Rhodes, of Canterbury, bought out Sir George Whitmore. His manager, Mr. Seale, in order to

68 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

give employment to a brother, made great plantations, but Rhodes looked on this as an unnecessary expense, and it was discontinued; but I always feel grateful to Seale for the long belts of trees that now shelter my home.

In 1882, 35,225 acres of Rissington were cut up and sold, and my father, Francis Hutchinson, bought the homestead block. His son, also Francis, now owns the adjoining station, Omatua.

The five-horse coach that made a daily journey from Napier past Rissington to Puketiritiri was one of the last to run on the Hawkes Bay roads. The big traction engines, each drawing two waggons loaded with timber from the Puketiritiri bush or produce for the settlers, were a terror to the coach horses, and motor vehicles were equally alarming. Indeed when cars first made their appearance on the narrow, winding roads it was quite a usual thing for settlers to ring up their neighbours to warn them to take care if they were going to town in their buggies.

18. THE STORY OF JOHN AND MARY HAMELING

By M. Moriarty, Ohinewai W.I.

This is a tale that was told to me by my grandmother, many years ago, and if I close my eyes, I can still see her sitting with her hands folded and a far-away look in her eyes, as she talked to me of her father and mother, and of her own life as a girl.

It was near where Waipawa now stands that John Hameling came with his wife and kiddies to make a home – sometime in the early sixties as nearly as I can determine without

HAWKES BAY 69

having exact dates to go by. Grannie was then nine years or so of age, the Maori wars were raging, and some fierce battles were being fought in various parts of the country.

The handful of white settlers at Waipawa were drawn even more closely together than usual by their common danger. They had little communication with the outside world, though occasionally someone from a neighbouring settlement would ride in with news, or one of their number would have to go for stores. How eagerly were these men questioned when they returned. “Were there any new arrivals from Home?” All English papers were passed round, and even though they were months old, they were, oh, so welcome. Eagerly the women chattered and laughed, and fear was chased away by a wee bit of news from Home, so many thousands of miles away.

On one such occasion the men drew away from the women, and their faces clouded with anxiety. Fearfully, they listened to the news that a rider had brought them. A party of raiding Maoris was passing swiftly through the country, burning and pillaging as they went, terrifying the women and children, and in some cases, rumour had it, slaying them. Hastily the settlers made their plans. They selected the strongest dwelling for a fort, though they realised how pitifully inadequate it would be against a determined attack.

Some distance away across the river was a strong pa. The natives seemed friendly enough, but John Hameling never forgot that not so very long before they had been cannibals. With this thought ever in his mind, he had, some time previously, made provision for the safety of his wife and children in case of danger.

At the back of his house were steep hills covered with tall fern which came right to his back door. He did not wish to alarm his wife, but quietly searched amongst these hills until he found a deep depression, possibly caused by

70 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

some old-time landslide, but now covered and almost hidden by fern. He widened and deepened the hollow, digging into the hillside until he had a cave that would hold several people in comfort. It was hard work, not done in a day. But the thought of his loved ones spurred him on. At last the retreat was finished, and he took his wife and showed her just where she was to go in the event of an attack. Between them they stocked it with provisions sufficient to last ten days, and he instructed her how to draw down the fern so that the entrance was completely hidden.

Shortly afterwards came the news of the approaching raiders. Hastily John Hameling led his wife and children through the tall fern to the cave, and after kissing them each in turn, he sadly and carefully closed the entrance, and returned to his home knowing that he might never see his loved ones again.

Gathered together, the men of the settlement grimly awaited the coming of the savages. What could they do. Just a handful of brave men, but every one willing to fight, and if need be, to die, to protect their families. Hour after hour went by and still there was no sign of the enemy. Night descended on the group of expectant men. Suddenly a voice spoke sharply:

“Hark! A rider comes! He’s travelling fast!”

Someone hurried to meet him as he hastily dismounted.

The watching men were breathless, striving to see the faint shadows of the two returning through the darkness. Minutes seemed hours till they both burst in. And then such news, such cheering and handshaking! Such relief showing on their faces! The raiders had encountered a party of warriors from the friendly pa, who attacked them. A furious battle had taken place and the few surviving marauders had fled back through the bush.

As soon as he knew that all danger had passed. John Hameling dashed through the fern, stumbling in the darkness,

HAWKES BAY 71

but always hurrying on. Tearing open the carefully hidden entrance to the cave he clasped his wife and children to him.

Back at last in their own little house, Mary Hameling heard the story of the victory of the friendly Maoris. Heard, too, of the anxious hours of waiting, especially after night fall; and in her sympathy for her husband, she lived through those hours again with him. She made little of her own terrors, the absolute darkness in the cave after their only light had been accidentally extinguished; the frightened sobbing of the little ones, until at last she soothed them all to sleep, except little Mary, my Grannie, who crept within the shelter of her mother’s arm. Huddled together, they sat and waited the long night through, listening for the sounds of guns, the expected cries of the natives, and failing to hear them, becoming a prey to their thoughts. Had the settlers all been killed without a chance to defend themselves? Would the war party move on at daybreak, or would they stay? But not one word of all this did she tell her husband. No, rather did she thank God for bringing him safely back to her. Tears filled her eyes; hastily she dashed them away, and turned a smiling face to him, her own experiences forgotten in her great thankfulness.

72 TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN

19. HISTORY OF THE WAIKOPIRO BLOCK

By Members of Waikopiro W.I.

According to tradition the Maoris came to *Whetukura some 150 to 160 years ago. They built a large pa at the back of Whetukura, a splendid natural fortress with three steep sides, and a getaway along a ridge. About 135 years ago the pa was occupied by a large number of Maoris, and during one big tribal fight over 400 warriors were killed there.

When the land was first opened up for European settlement, a wall of the old palisading still remained, but now, owing to fires and other causes, there is only one solitary pole to mark the site of the old fortress.

There are also remains of another old fort, situated a little further out, on Mr. Williams’s property, which was the scene of a massacre about 110 years ago. This pa was built on the top of a pinnacle, with cliffs round three sides; and there were three fences erected on terraces in the front with a gateway at one end. History says that the warriors were away fishing and hunting to the south-east, when a hostile tribe came from the north-west, and found the pa occupied only by old men, women, and children. The invaders massacred these defenceless people and went back the way they had come.

When the warriors returned home the next day, and saw the tragedy that had been enacted in their absence, they immediately set out to avenge the murder of their fathers, mothers, wives, and children.

The invaders, learning that the warriors were on their path, hid all their tikis and other valuables in a limestone

* Red star.

HAWKES BAY 73

cave, and closed the entrance. They were soon overtaken by the avengers; all were slaughtered, and their bodies were thrown into a stream, which was named Waikopiro, Foul or Rotten Water – a name it bears to this day. The whole tribe perished, and their treasures are still believed to be hidden in the cave, which no man has ever found, though many have searched for it. It is thought that the Tiki, or Deed Stone of the district, was lost during the battle. In 1904 a greenstone tiki was found at Whetukura, and for a time there was intense excitement amongst the Maoris, who believed that this was the missing Deed Tiki; but it was not.

Evidences of former Maori occupation of the district are still found – axes, implements of various kinds, and potato pits.

During the eighties, when Mr. Seddon came into power, Mr. Hall, member for the district, persuaded the Government to open up Waikopiro for settlement. The first block was cut up into small sections called State Farms, which were balloted for in 1896, and settlers soon arrived to carve out homes in the bush. Shortly afterwards, Waikopiro Block No. 2 was opened up. Most of the first settlers were dairy farmers, the land not being suitable for sheep until it had been cleared. When it was possible to put sheep on the land, they could be bought for 2s 6d a head.

There were hundreds of wild pigs and cattle, and the settlers used to hunt them for food. The pigs were said to be descendants of those liberated by Captain Cook so many years ago, and the cattle were sired by a stud Shorthorn bull imported by the late Mr. J. D. Ormond of Wallingford, which got away into the bush shortly after arriving in Hawkes Bay. This bull was eventually shot, and his hide was found to weigh 90 pounds.

We often wonder how the pioneer women managed so well, and were so hospitable, when all their cooking was

TALES OF PIONEER WOMEN 74

done under primitive conditions, frequently in camp ovens, or even over open fires.

Prior to the opening up of the land for settlement, there was just a rough track cut through the bush from Ormondville to Whetukura. Travelling over it was a nightmare even in daylight, but if darkness overtook the traveller, he just had to stay where he was, light a fire, and wait for the morning. All stores were taken in on pack-horses, when procurable. When no horses were procurable, the settlers themselves had to take their place, and carry the loads on their own backs. Many a load has slipped from a pack-saddle while the horse was crossing, a particularly steep papa face leading down to the worst creek on the track, and the precious tea, sugar, and flour, fallen into the water. One can imagine the disappointment of the poor woman, longing for fresh groceries, on finding when at last they arrived, that they were wet, and almost useless – though not quite, for pioneer housewives were not easily defeated.

Later, the bush track was widened to six feet, which was a help to the settlers; and still later, a 14-foot road was formed and metalled.

The mail was delivered in Whetukura by Mr. Lucas, who walked three times a week into Ormondville, and received £5 a year for his contract. The carrier in those days was Mr. J. Smith with his team of bullocks, who carted iron, metal, stores, and other goods into Whetukura and returned to Ormondville with a load of totara posts, firewood, wool, and other farm produce.

Very soon came a P.O. store, and in 1898 a school was built for 50 or 60 pupils. Then came a village hall, and in 1902 or thereabouts a blacksmith’s shop and creamery were opened; but a few years later the creamery was closed and the cream taken out to Mr. Nikolaison’s factory at Ormondville.

In 1923 the Waikopiro Maori block was opened up for

HAWKES BAY 75

returned soldiers, and the five sections were balloted for. This land was “tapu-ed” by the Maoris on account of the massacre that had taken place there so many years before.

In course of time some of the dairy farmers sold out to their neighbours, who in turn sold out, and now the holdings are quite large compared with the original State farms. The majority of settlers in Waikopiro to-day are sheep farmers: the land is very fertile, and little remains of the dense bush and scrub in which the wild cattle and pigs used to roam.

Non-commercial use

This work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 New Zealand (CC BY-NC 3.0 NZ).

Commercial Use

Please contact us for information about using this material commercially.Can you help?

The Hawke's Bay Knowledge Bank relies on donations to make this material available. Please consider making a donation towards preserving our local history.

Visit our donations page for more information.

Description

Other surnames in this book excerpt –

Alexander, Anderson, Beattie, Carr, Craig, Finlayson, Gray, Harding, Hellyer, Lavin, Loisel, Lucas, McCarthy, McIntyre, McNeil, Nesfield, Nikolaison, Seale, Skipworth, Torr, Villers, Wilkie, Williams

Subjects

Tags

Format of the original

Book excerptDate published

1940Creator / Author

- A E Woodhouse, Editor

Publisher

Whitcombe & Tombs LimitedPeople

- Geraldine Absolom

- Niall Alexander

- Roy Andrews

- Frank Bee

- George Bee

- J Begley

- Margaret Cassie

- Reverend W Colenso

- F B Gibson

- William Gilmour

- W S Greene

- Herbert Guthrie-Smith

- John Hameling

- Mary Hameling

- Amy H Hutchinson

- Francis Hutchinson

- Francis Hutchinson

- Amy G Kane

- Alick Knox

- Kenneth Mackenzie

- Willina Mackenzie

- Mr and Mrs J B McKain

- Margaret Moriarty

- D Nicholls

- J D Ormond

- A Reeves

- Robert Rhodes

- David Ross

- Frances Ross, nee Bee

- J Sim

- J Smith

- A E Jerome Spencer

- J Stevens

- James Tait

- John Tait

- Te Kooti

- W Thompson

- Major Von Tempsky

- Colonel and Mrs George Whitmore

- Mrs Henry Williams

- Henderson Wilson

- A E Woodhouse

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.