LIVING TREASURES

kilns are available for inspection by interested visitors.

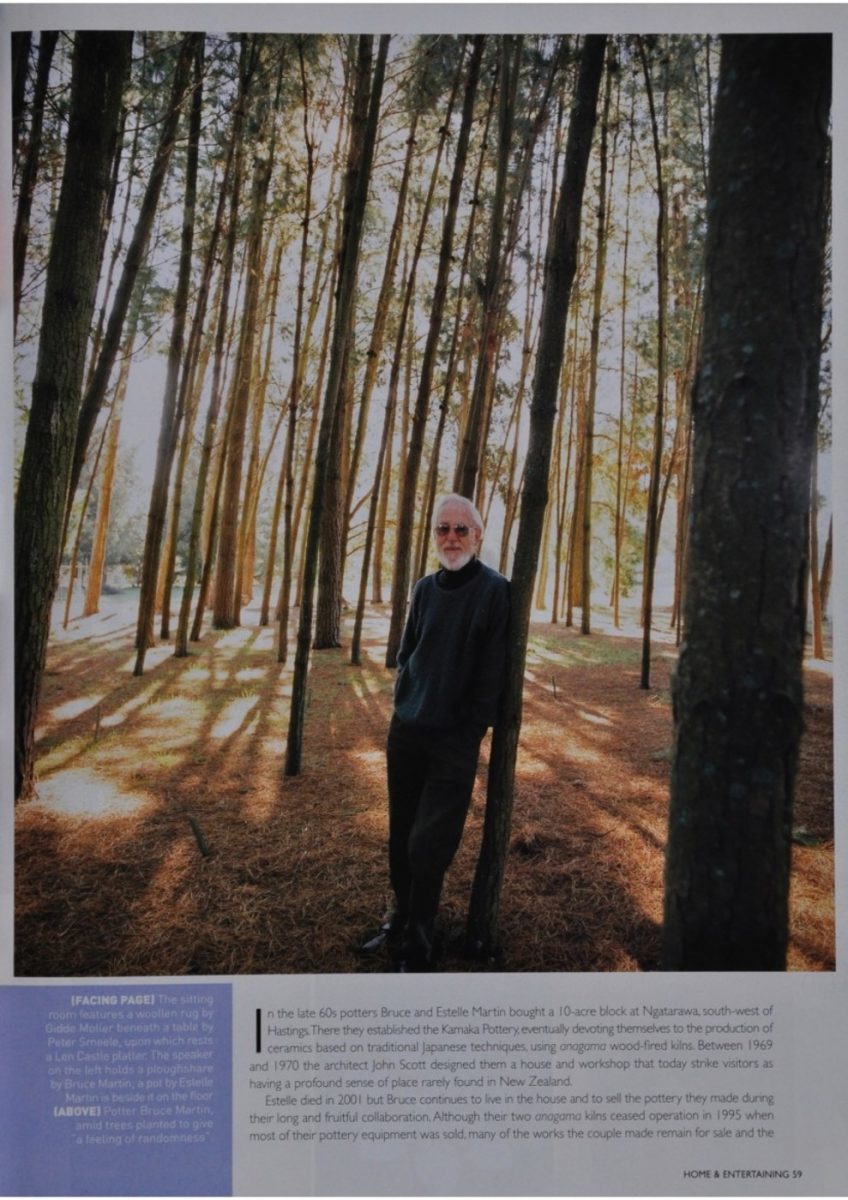

Pottery began for Bruce and Estelle Martin in the late 50s when, tired of the omnipresent white swan vases people invariably used for flower arrangements, the couple decided that the only way to make something they liked was to do it themselves. Pottery classes and clay modelling followed and the pair were hobbyists for about five years.

Then, early in 1965, the great Japanese potter Shoji Hamada demonstrated his unique skills to a Napier audience. Already acquainted with those indispensible [indispensable] volumes, Bernard Leach’s A Potter’s Book and Soetsu Yanagi’s The Unknown Craftsman, Bruce and Estelle took a greater interest in things Japanese. Estelle had taken classes in ikebana flower arranging and admired the pottery containers that her Napier teacher, Lou Theakstone, had brought back from a visit to Japan. The couple began making similar objects in an oil-fired kiln.

Later in 1965 Bruce and Estelle made the decision to set up a partnership in Hastings as potters – fulltime. During the following years the Martins made readily saleable, glazed domesticware, as did many other New Zealand potters.

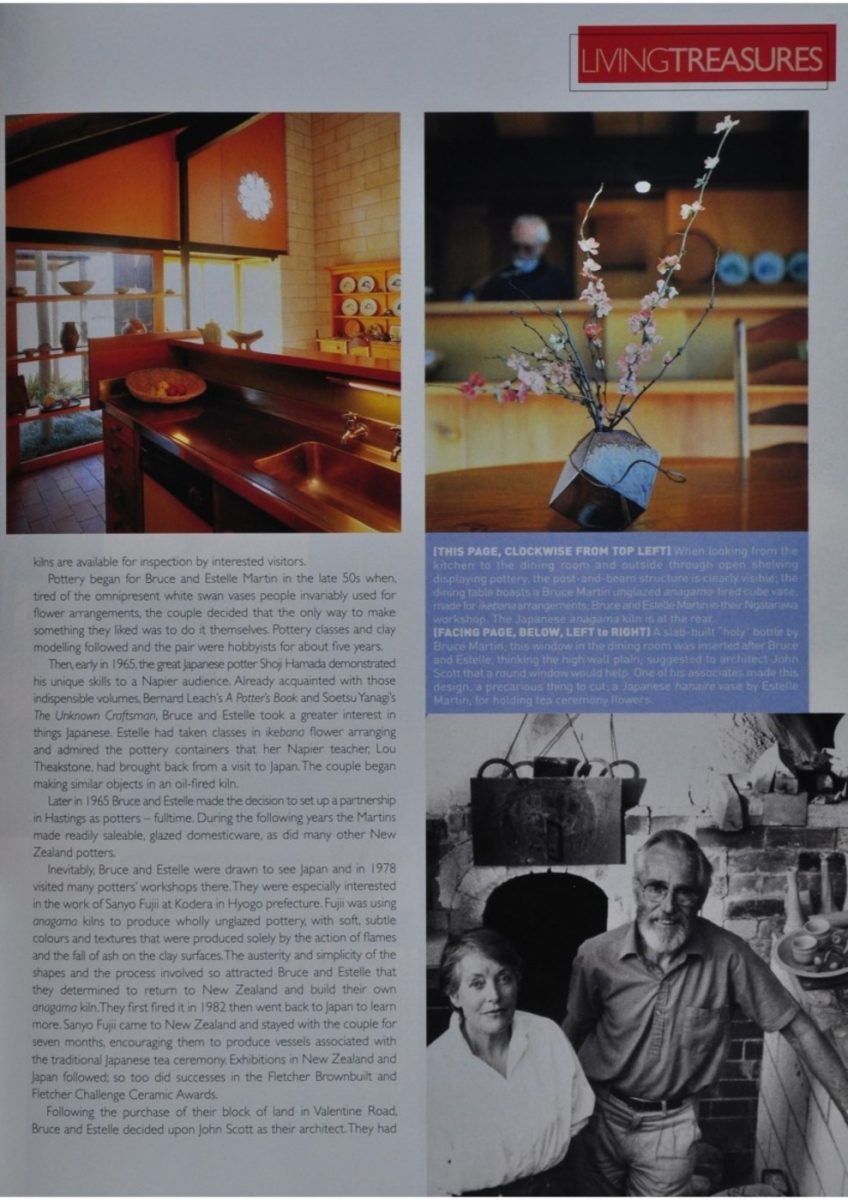

Inevitably, Bruce and Estelle were drawn to see Japan and in 1978 visited many potters’ workshops there. They were especially interested in the work of Sanyo Fujii at Kodera in Hyogo prefecture. Fujii was using anagama kilns to produce wholly unglazed pottery, with soft, subtle colours and textures that were produced solely by the action of flames and the fall of ash on the clay surfaces. The austerity and simplicity of the shapes and the process involved so attracted Bruce and Estelle that they determined to return to New Zealand and build their own anagama kiln. They first fired it in 1982 then went back to Japan to learn more. Sanyo Fujii came to New Zealand and stayed with the couple for seven months, encouraging them to produce vessels associated with the traditional Japanese tea ceremony. Exhibitions in New Zealand and Japan followed; so too did successes in the Fletcher Brownbuilt and Fletcher Challenge Ceramic Awards.

Following the purchase of their block of land in Valentine Road, Bruce and Estelle decided upon John Scott as their architect. They had

Photo captions –

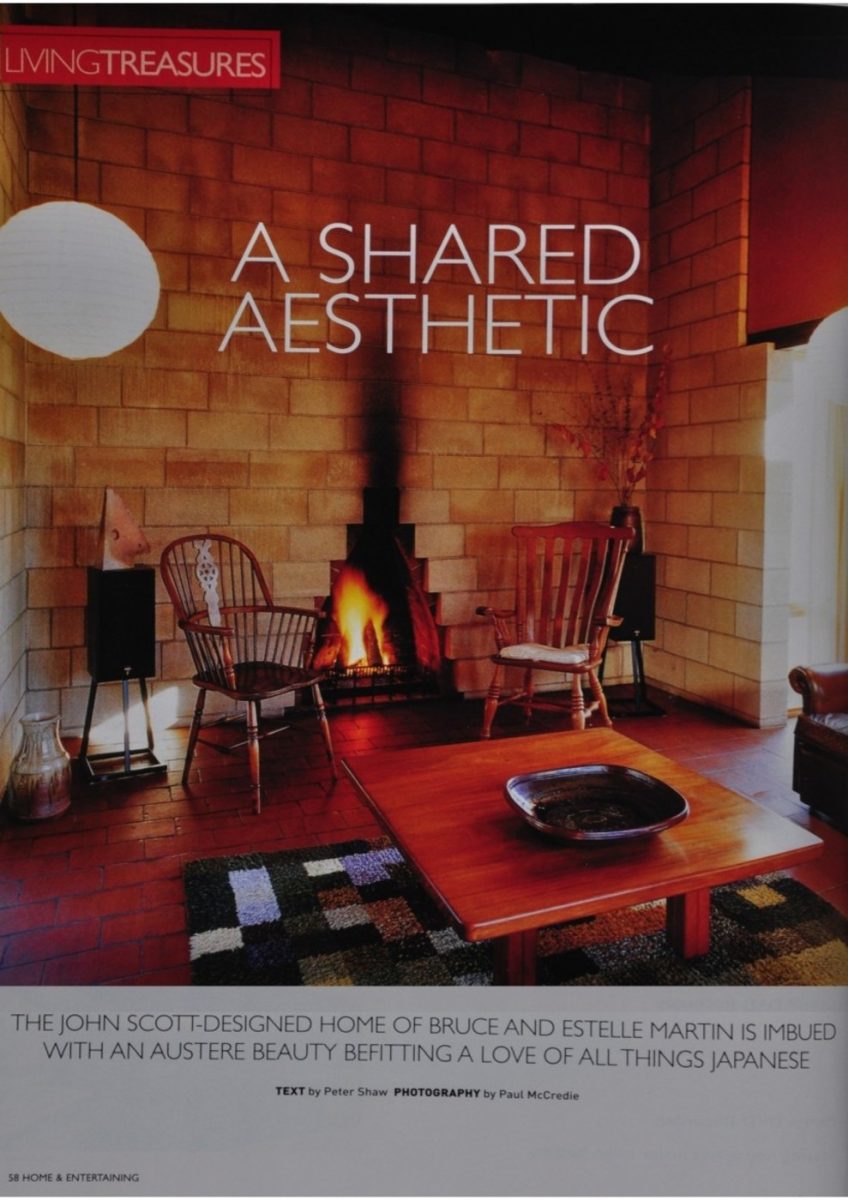

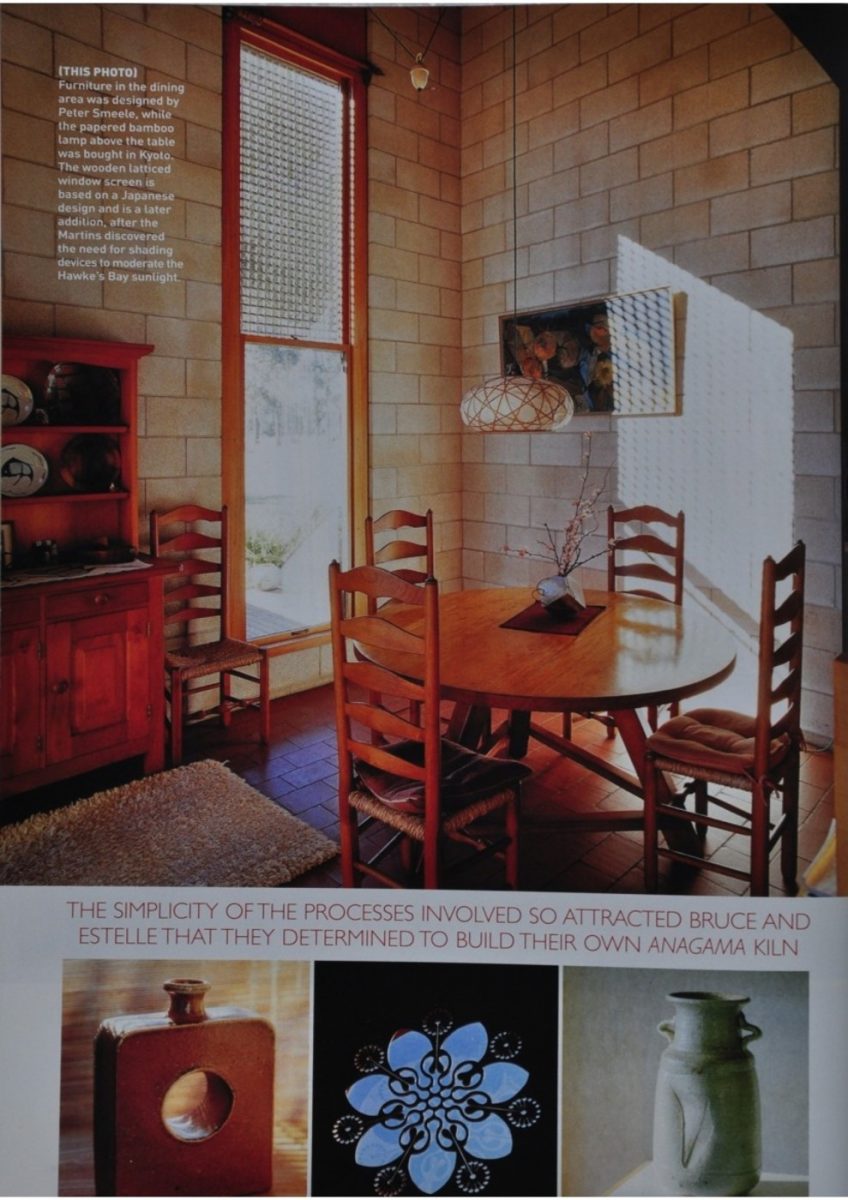

(THIS PAGE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT) When looking from the kitchen to the dining room and outside through open shelving displaying pottery, the post-and-beam structure is clearly visible; the dining table boasts a Bruce Martin unglazed anagama-fired cube vase, made for ikebana arrangements; Bruce and Estelle Martin in their Ngatarawa workshop. The Japanese anagama kiln is at the rear.

(FACING PAGE, BELOW, LEFT to RIGHT) A slab-built “holy” bottle by Bruce Martin; this window in the dining room was inserted after Bruce and Estelle, thinking the high wall plain, suggested to architect John Scott that a round window would help. One of his associates made this design, a precarious thing to cut; a Japanese hanaire vase by Estelle Martin, for holding tea ceremony flowers.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.