DESIGNED TO LAST

EVEN BEFORE HIS DEATH IN 1992 at the age of 68 John Scott was passing into legend. The architect had designed one of the most acclaimed buildings of the post-war era, Futuna Chapel (1961) at Karori in Wellington, as well as several other distinctive churches and institutional buildings, and a series of singular houses, many in his native Hawkes Bay [Hawke’s Bay]. Impressive as Scott’s work was (and posthumously, his reputation grows ever larger), his renown also has much to do with the way he worked, and the way he lived. “Brilliant, mercurial, usually barefoot, he worked all hours of the day and night and followed his own schedule,” writes Scott’s biographer Russell Walden in The Dictionary of National Biography. “He was no manager, nor did he make much money. However, his attitude to his profession was one of complete integrity.”

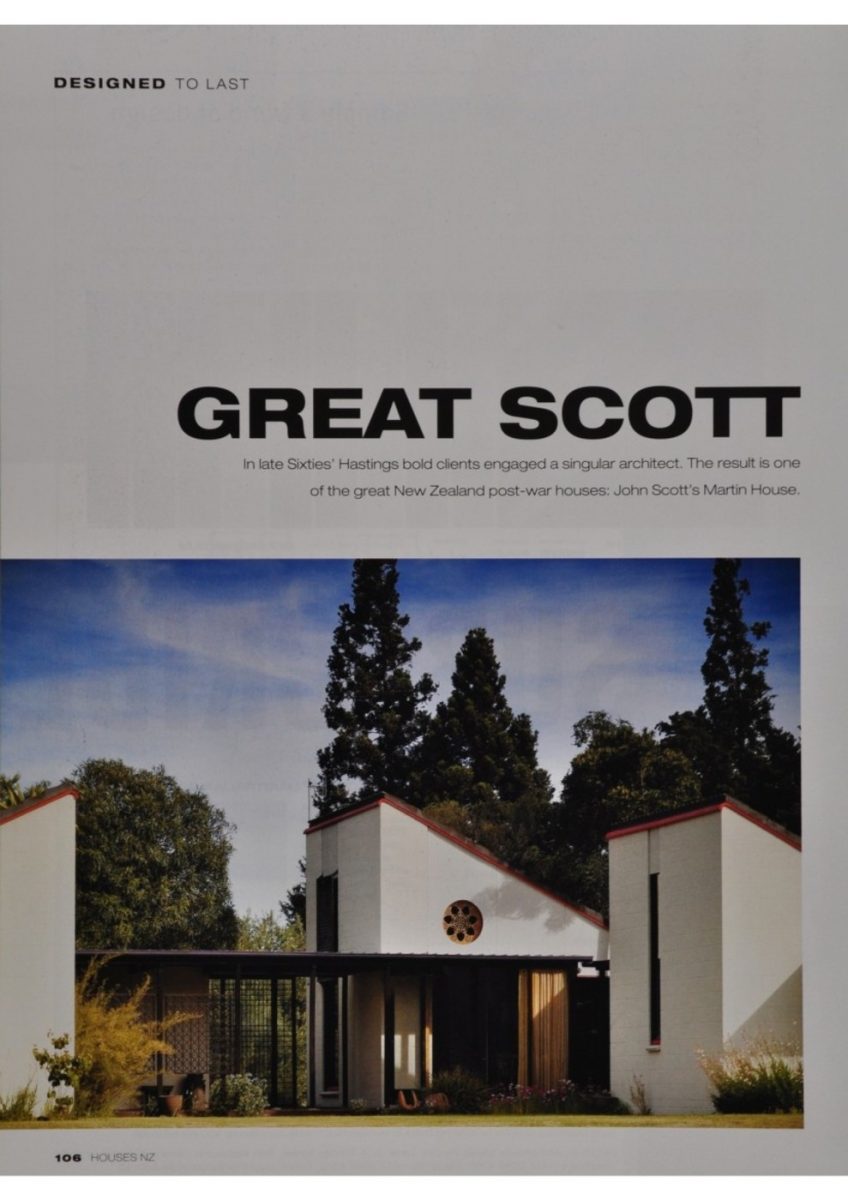

The problem with reputation is that it can cloud appreciation. You think you know about someone or something, but you really don’t; you think you’ve seen something, but you haven’t. You’ve just taken it for granted. With some buildings, what architects are wont to say is right: you just have to be there. The house John Scott designed in the late ’60s for the potters Bruce and the late Estelle Martin has been published in magazines and books over the years, but in actuality it is still a surprise. The house, located near Bridge Pa on the outskirts of Hastings, can only be glimpsed from the country road that passes by its 10-acre site – over the years the Martins planted their once-barren property with numerous trees, now matured. No driveway leads to the house; visitors have to take their cars on a slow slalom across the lawn.

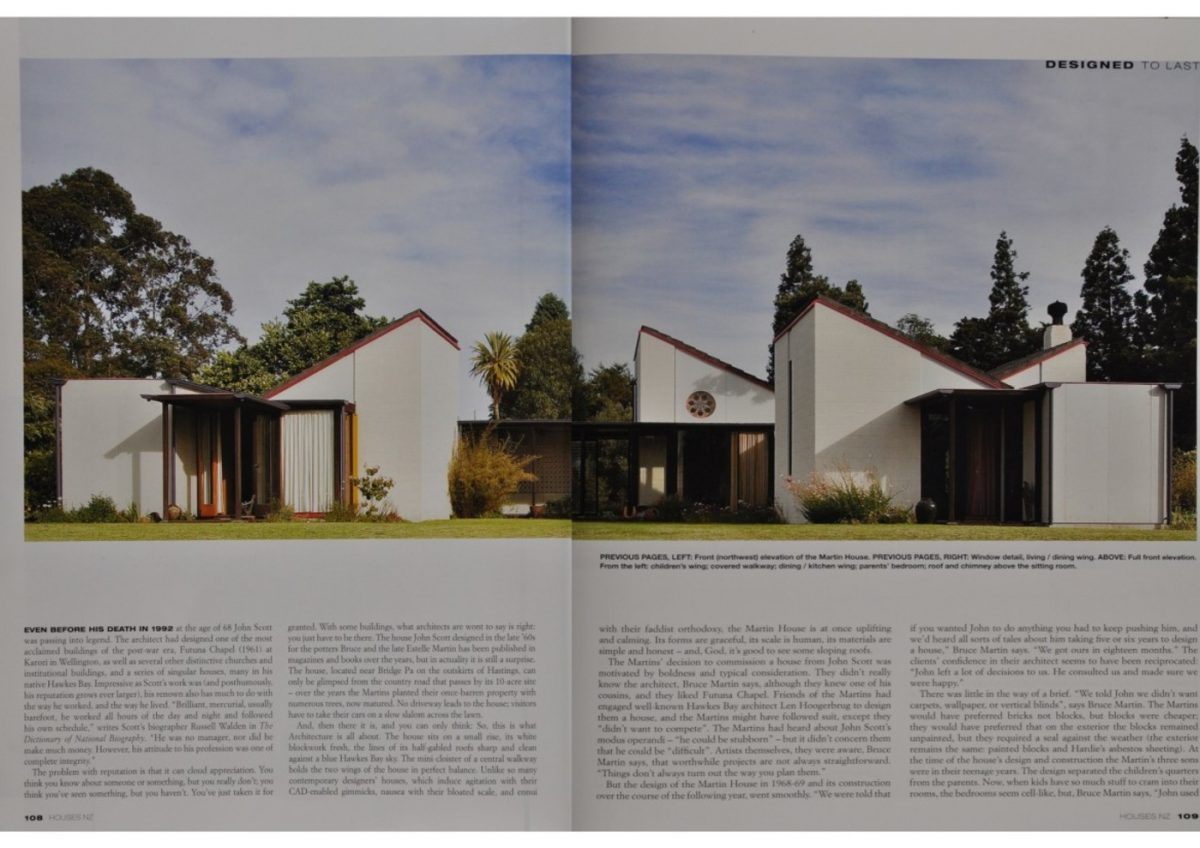

And, then there it is, and you can only think: So, this is what Architecture is all about. The house sits on a small rise, its white blockwork fresh, the lines of its half-gabled roofs sharp and clean against a blue Hawkes Bay sky. The mini-cloister of a central walkway holds the two wings of the house in perfect balance. Unlike so many contemporary designers’ houses, which induce agitation with their CAD-enabled gimmicks, nausea with their bloated scale, and ennui with their faddist orthodoxy, the Martin House is at once uplifting and calming. Its forms are graceful, its scale is human, its materials are simple and honest – and, God, it’s good to see some sloping roofs.

The Martins’ decision to commission a house from John Scott was motivated by boldness and typical consideration. They didn’t really know the architect, Bruce Martin says, although they knew one of his cousins, and they liked Futuna Chapel. Friends of the Martins had engaged well-known Hawkes Bay architect Len Hoogerbrug to design them a house, and the Martins might have followed suit, except they “didn’t want to compete”. The Martins had heard about John Scott’s modus operandi – “he could be stubborn” – but it didn’t concern them that he could be “difficult”. Artists themselves, they were aware, Bruce Martin says, that worthwhile projects are not always straightforward. “Things don’t always turn out the way you plan them.”

But the design of the Martin House in 1968-69 and its construction over the course of the following year, went smoothly. “We were told that if you wanted John to do anything you had to keep pushing him, and we’d heard all sorts of tales about him taking five or six years to design a house,” Bruce Martin says. “We got ours in eighteen months.” The clients’ confidence in their architect seems to have been reciprocated: “John left a lot of decisions to us. He consulted us and made sure we were happy.”

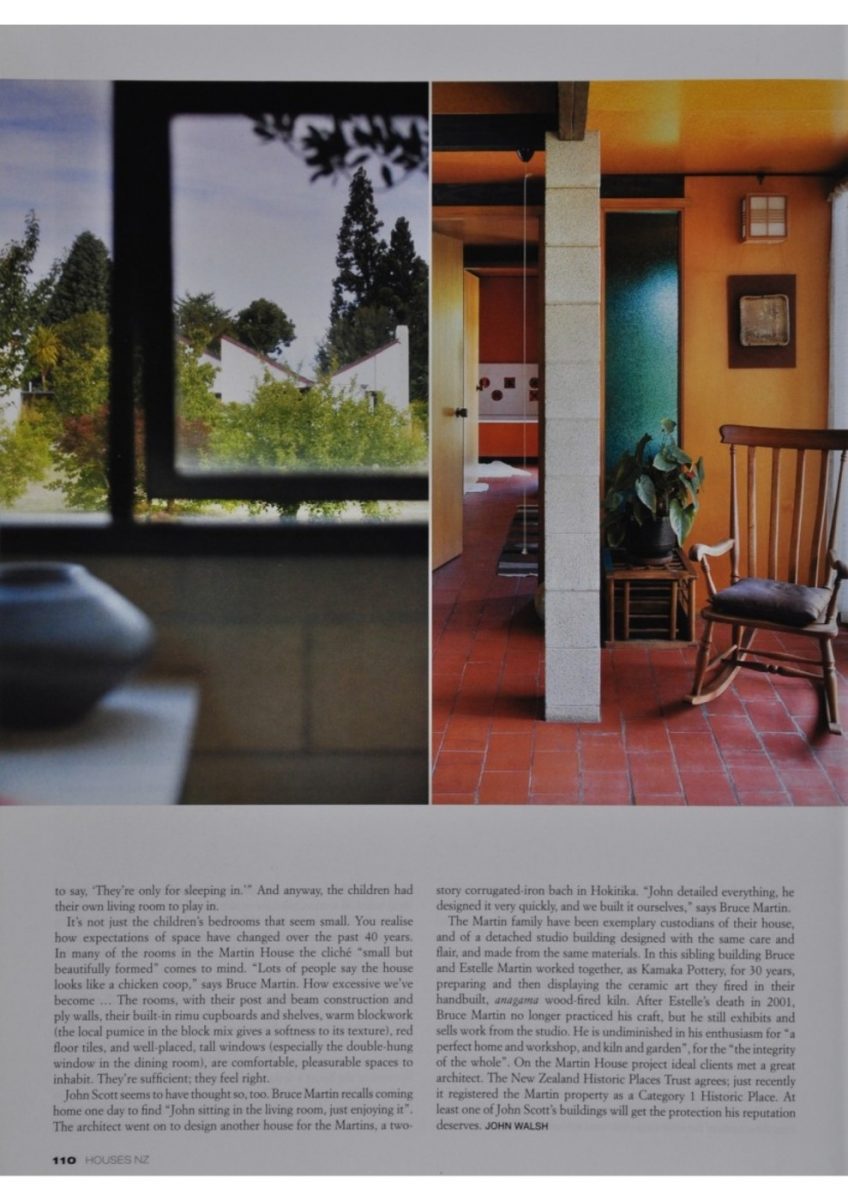

There was little in the way of a brief. “We told John we didn’t want carpets, wallpaper, or vertical blinds”, says Bruce Martin. The Martins would have preferred bricks not blocks, but blocks were cheaper; they would have preferred that on the exterior the blocks remained unpainted, but they required a seal against the weather (the exterior remains the same: painted blocks and Hardie’s asbestos sheeting). At the time of the house’s design and construction the Martin’s three sons were in their teenage years. The design separated the children’s quarters from the parents. Now, when kids have so much stuff to cram into their rooms, the bedrooms seem cell-like, but, Bruce Martin says, “John used

Photo captions – PREVIOUS PAGES, LEFT: Front (northwest) elevation of the Martin House. PREVIOUS PAGES, RIGHT: Window detail, living / dining wing. ABOVE: Full front elevation. From the left: children’s wing; covered walkway; dining / kitchen wing; parents’ bedroom; roof and chimney above the sitting room.

108 HOUSES NZ HOUSES NZ 109

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.