Margaret Walmsley (nee Gilbertson) feels truly blessed to have grown up in Hastings where she had an abundance of freedom, but also knew her limits.

Lambs tails, teacake and family picnics

Growing up in the Bay

My parents, Douglas Gilbertson, an accountant with Rainbow and Hobbs, and my mother, Joceline (nee Nelson) were of farming families.

I was the younger of two daughters, my sister Josephine being three years older than me. Home was near the Duke Street end of Grays Road – a three-bedroom weatherboard house that cost the equivalent of $900 in 1933.

Born in 1937 my childhood was greatly influenced by the depression – not long past and World War 2 which began 2½ years later. We lived quite near Cornwall park; houses were dotted in groups with open spaces around – government houses came much later – and there was no building in war time,

There were a few houses in Duke Street between Grays Road and St James’s Hall where we went to Sunday school. Across the road from the hall was the beautiful home of the Rochfort family.

The area of Tawa, Rata and Rimu Streets, later known as Kilchatten Park, was several large paddocks, as were all the areas later used for government housing.

The Scout hut in Duke Street had an old rubbish dump nearby. Piles of wood and old drums provided material for makeshift boats and paddles. This area and Cornwall Park were the setting for endless imaginative games.

l would have been barely four years old when my eight-year-old cousin, seven-year-old sister and I would set off for Cornwall Park, something we did happily and safely for many years.

We climbed the lions, as did generations before and after us. We paddled in the pool, climbed up the slide, swung on the swings and spun the merry-go-round as fast as we could. We fed the ducks, pressed our noses to the wire-netting cages which housed a collection of exotic birds and the lucky ones sailed toy yachts on the lakes. The rest of us had just as much fun with little boats we made with half-walnut shells. On rare occasions we could buy a tiny one-penny ice-cream from Mrs Applebee, who ran the playground kiosk and who surely deserved a medal for acting as our talking clock.

Because of her we usually arrived home on time. We were never bored. Skipping, hopscotch, rounders, bullrush, and what’s the time Mr Wolf? were favourite games of the very young.

By the time I was nine yours old, friend Robyn and l were considered trustworthy enough to ride our bike to the old Pakowhai River – now Pakowhai Country Park. Rules were simple, stay in sight of the bridge and no swimming.

Building dams to house the collection of shrimps, tiny eels, found under stones and cockabullies, kept us well amused.

Riding home along Pakowhai Road we passed first through the beautiful poplar avenue which had sprung up from poles set in the ground as fence posts.

The sealing on the road was very narrow, about as wide as one traffic lane of the present day. In flood times the water would sometimes cover many acres of flat land as far as the present Palmer’s garden centre, then Wilson’s nurseries.

It is not surprising then that the road sides were very rough all the way to Stortford Lodge, and the same in Heretaunga Street. Cycling wasn’t a bit like it is today.

As we neared Duke Street and home, the huge prize Jersey bull known to us all as Breen’s bull would be waiting under the great oak tree. The bull – subject of many doubtless exaggerated stories of its ferocity, is long gone, but the tree still stands at Gracelands.

My sister and l shared a bicycle which meant doubling on expeditions around the district; perhaps to Havelock North to visit grandparents or slide on cardboard down grassy hills.

Golfers at Bridge Pa course must have alternately blessed and cursed us as we found balls that may or may not have been lost, and sold them back for threepence, and if they were unmarked, sixpence.

We roamed far and wide and if Mum worried, she never said. She herself loved the outdoors and would take us on picnics where she taught us to identify birds and their nests. Picnic food was a chop each, grilled over an open fire and put on a piece of thick bread as a plate. Sometimes we had potatoes cooked in a billy or thrown in the embers of the fire.

Billy tea came when we were older. With our farming connections, springtime saw us making a small fire in the back yard to cook lambs’ tails delivered by the sackful after docking.

The tails were thrown into the fire embers where the wool burned off and the flesh cooked in a few minutes. A squealing noise similar to that of a boiling kettle was the sign of a cooked tail.

The blackened tail would be raked out of the fire and left to cool a little before peeling the skin off to reveal the white flesh inside. Soon there would be a group of children with sticky, blackened faces and hands.

Golfers at Bridge Pa course must have alternately blessed and cursed us as we found balls that may or may not have been lost, and sold them back for threepence, and if they were unmarked, sixpence.

The Hawke’s Bay Spring Show provided the most eagerly awaited picnic of the year.

Bacon and egg pie was traditional for us, but for many farmers’ wives, show week baking was an enormous task as they prepared mountains of food for two days.

Other picnics are memorable not so much for the food as for the welcome break meal times provided on rare trips to Taupo. The road was long, narrow and very steep, with truly tortuous twists and turns. As it was unsealed it was either very muddy or very dusty.

Especially nightmarish was the last stretch over the Rangataiki Plains. Wheels caused deep ruts and corrugations which made driving difficult but the chalk-like pumice dust got in to every little crack and crevice.

Hair-washing was a necessity on arrival in Taupo, as one couldn’t get a brush or comb through one’s hair.

At five years old I walked with my mother down the long lane to Mahora School. Mr Engebretsen was the headmaster and Miss Satchel the infant mistress. Strangely Miss Satchel had been infant mistress at a country school when my uncle first began many years earlier. This was 1942, the middle of the war years. Monday mornings were marked by a patriotic ceremony where we gathered around the school flagstaff. With fervour we sang God Save the King, God Defend New Zealand and the Star Spangled Banner. This was followed by a little recitation which went thus: “I honour my God, I serve my King, I salute my Flag.” Wonderful marching music was played as we trooped, arms swinging vigorously, into school. I have vivid memories of Colonel Bogey and other marches from this time.

Some months after the war finished, staff and pupils gathered in the playground at the back of the school.

Here our sense of excitement was replaced by absolute awe as we witnessed the sight of an enormous Lancaster bomber appearing seemingly just above the gum trees. Even today, low as it was, it would seem big, but then when the only planes we saw were the little yellow Tiger-Moth biplanes from Bridge Pa, it was huge!

Life was punctuated with reminders of the war. In the beginning Dad went away to Air Force camp. At times he was at Trentham, Whenuapai, and Ohakea giving me my first awareness of geography. There were shortages: needles and knitting needles caused me personal grief through misdemeanours.

Later I became aware of rationing. There were little passport-sized booklets with pages marked in the squares. Some of these little squares would be cut out each time items like sugar, butter, tea, clothing etc. were purchased. Petrol coupons were different – they came in thin cardboard sheets and the individual stamps were larger.

We were more fortunate than some as Mum was a very good vegetable gardener and grew all and more than we needed. She also kept fowls, whose eggs were preserved first with a vaseline-like product called ovaline and later in a kerosene tin full of waterglass mixture (isinglass). Yuk! All fat from meat – mostly mutton, was saved in a kerosene tin and exchanged for washing soap.

My mother worked hard for the war effort. She grubbed carrots for the Internal Marketing Division (IMD) and picked apples – dark red and delicious at Paynter’s orchard in Havelock Road. I remember being mystified by the net that grew on our front verandah – the first of several camouflage nets she made. Biscuits were baked for Red Cross parcels for the prisoners of war, and when food parcels were packed for overseas, they were wrapped in old sheeting which was sewn together into a very secure covering. Mum seldom sat down without picking up the latest pair of socks she was knitting for the troops.

Each pair always had a little tiny golliwog, made of wool scraps, sewn on for luck.

We were among the many families who billeted American servicemen on leave.

Very relevant today was the acute energy shortage. Coal was in very short supply and as gas was made from coal, there was very little for cooking – mainly by gas then. A long-handled enamel saucepan was purchased and used to boil vegetables over the open fire and then the saucepan was refilled with water for washing up. The best childhood bath I remember was when as a desperate measure the copper was boiled and I sat in the warm washhouse in the wooden tub with deep water instead of the usual two inches my sister and I shared. Even if my knees were under my chin, it was real luxury.

War-time memories could be almost anywhere but going to town was uniquely Hastings. Milk was delivered by Mr Tweedie every morning – ladled directly into jug or billy. Groceries were delivered once a week by Mr Cooper, whose shop was half-way along Grays Road, so going to town was different. No one-stop shopping then. Firstly we had to get dressed up, really dressed up, shoes polished, hair tied down, and “don‘t you dare get dirty” ringing in our ears. I distinctly remember Mum wearing a little fox fur, complete with beady-eyed head which made me very unhappy.

Setting out from home in our little Austin 10 car, we would travel along Grays Road. The roadsides were very steep and covered in long prairie grass – the seal was a narrow strip. As I said before, Heretaunga Street was also only sealed in a narrow strip with unsealed stony areas each side, and treacherously deep gutters.

Once in Heretaunga Street we would pass Odlin’s timber yard on our right, and then on the left was Dunningham’s service station for petrol. This is now a video shop. A little further on the left, at the corner of King Street and Heretaunga Street, was the Cosy picture theatre – later the Embassy. Opposite the theatre on the right-hand side of Heretaunga Street is the scene of one of my most vivid and treasured memories of the Hastings I first remember. I think it must have been about 1940-41. At that time Hastings was well served by two family-owned bus companies. Nimons, with the familiar green and ivory buses which did the Havelock, Hastings Hospital run and Frethey’s with milk-chocolate coloured buses which did suburban Hastings and Fernhill.

There was a bus stop for the Fernhill bus outside the De Elsa woolshop, opposite the Cosy Theatre. It was usual to see a group of up to 20 elderly Maori women and a few old men waiting here. As they gathered together they were talking away in a language I now realise was Maori; by their sides were large kit bags (kete) filled with newspaper-wrapped parcels and in their hands they held white clay pipes which they were smoking. What I recall most vividly about these women is that under the creases of those aged faces, all the women had the soft blue-grey lines of the tattooed moko on their lips and chins. The whole scene was repeated regularly and was so unique that though I was four years old at the time, I recall it vividly more than 60 years later. Once I began school I didn’t see them again.

Many more memories of shopping are unique to Hastings. Businesses were largely family-owned except for chainstores like Woolworths and McKenzies. These stores had long wide aisles running the length of the shop. On eitpartlyher side of the aisle were counters with little compartments holding everything from safety pins to singlets. Behind the counters were the very glamorous shop girls, black frocks, white collars, long red fingernails. Some of the many family owned shops were big clothing stores such as Roach’s, Bairds, Westermans, men’s outfitters like Blackmores, Millar & Giorgi, Poppelwells, variety stores like Bon Marche, anpartlyd Hunts, toys – Bunkers, Onward Cycles, as it says, Fletcher’s and Thompson’s butchers and Hector Jones electrical, not to mention F L Bone, Garlands and Grieves Jewellers and so many, many more.

Hastings was very much a market town for country business with stock and station firms abounding. Williams and Kettle and Hawke‘s Bay Farmers were but two of many. Both had grocery departments run by men in spotless white aprons, but the Hawke’s Bay Farmers was special. They had a lift – the first in town – and it went up to the second floor with the tearooms. Entering the foyer to the tea rooms one could sense a feeling of pleasurable anticipation. Of those who experienced it, who could forget lunch or afternoon tea at the Farmers tea rooms. Red and white checked tablecloths, tiered cake stands, happy chatter, where town and country met.

I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but we had freedom in abundance – in return we knew our limits and obeyed the rules we did have. Money was scarce, treats few, but we lived freely in a benevolent and kindly society. Hastings was a wonderful place to grow up and we were truly blessed.

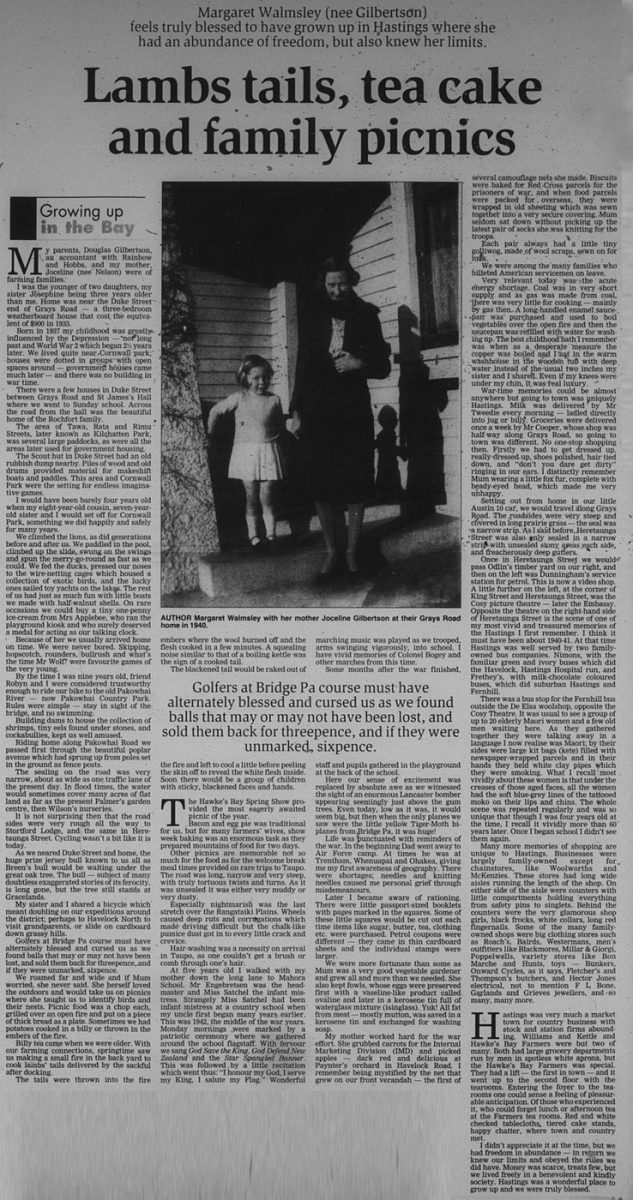

Picture caption –

Author Margaret Walmsley with her mother Joceline Gilbertson at their Gray’s Road home in 1940.

Do you know something about this record?

Please note we cannot verify the accuracy of any information posted by the community.