- Home

- Collections

- MILLER OA

- You Can't Keep a Good Idea Down - A celebration of the YMCA in Hawke's Bay 1890-1995

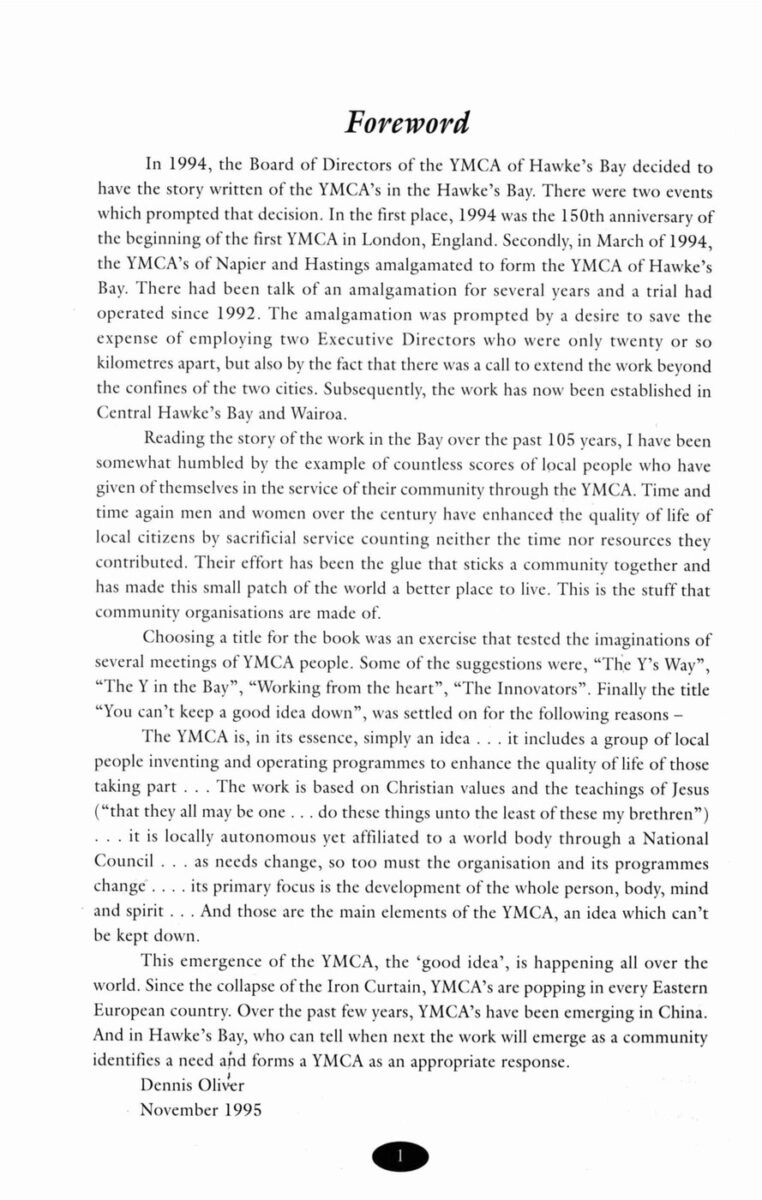

You Can’t Keep a Good Idea Down – A celebration of the YMCA in Hawke’s Bay 1890-1995

Page 1

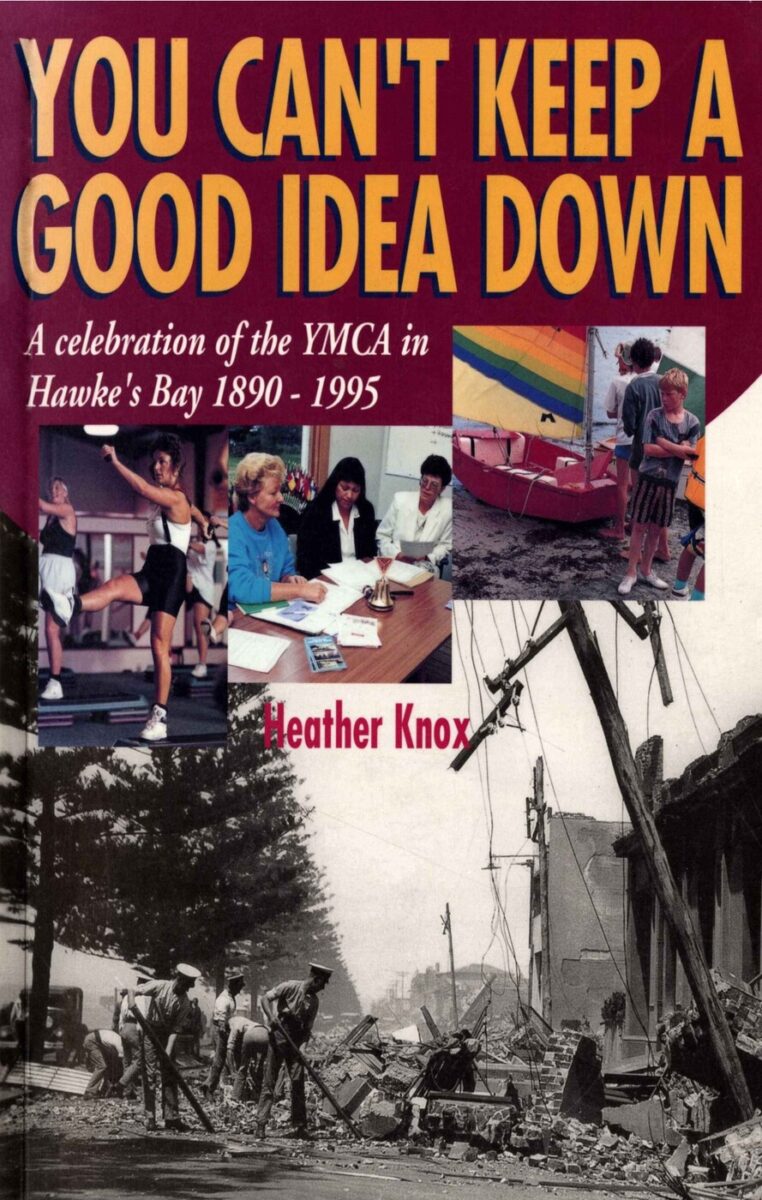

FOREWORD

In 1994, the Board of Directors of the YMCA of Hawke’s Bay decided to have the story written of the YMCA’s in the Hawke’s Bay. There were two events which prompted that decision. In the first place, 1994 was the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the first YMCA in London, England. Secondly, in March of 1994, the YMCA’s of Napier and Hastings amalgamated to form the YMCA of Hawke’s Bay. There had been talk of an amalgamation for several years and a trial had operated since 1992. The amalgamation was prompted by a desire to save the expense of employing two Executive Directors who were only twenty or so kilometres apart, but also by the fact that there was a call to extend the work beyond the confines of the two cities. Subsequently, the work has now been established in Central Hawke’s Bay and Wairoa.

Reading the story of the work in the Bay over the past 105 years, I have been somewhat humbled by the example of countless scores of local people who have given of themselves in the service of their commitment) through the YMCA. Time and time again men and women over the century have enhanced the quality of life of local citizens by sacrificial service counting neither the time nor resources they contributed. Their effort has been the glue that sticks a community together and has made this small patch of the world a better place to live. This is the stuff that community organisations are made of.

Choosing a title for the book was an exercise that tested the imaginations of several meetings of YMCA people. Some of the suggestions were, “The Y’s Way”, “The Y in the Bay”, “Working from the heart”, “The Innovators”. Finally the title “You can’t keep a good idea down”, was settled on for the following reasons –

The YMCA is, in its essence, simply an idea . . . it includes a group of local people inventing and operating programmes to enhance the quality of life of those taking part . . . The work is based on Christian values and the teachings of Jesus (“that they all may be one . . . do these things unto the least of these my brethren”) . . . it is locally autonomous yet affiliated to a world body through a National Council . . . as needs change, so too must the organisation and its programmes change . . . . its primary focus is the development of the whole person, body, mind and spirit . . . And those are the main elements of the YMCA, an idea which can’t be kept down.

This emergence of the YMCA, the ‘good idea’, is happening all over the world. Since the collapse of the Iron Curtain, YMCA’s are popping in every Eastern European country. Over the past few years, YMCA’s have been emerging in China. And in Hawke’s Bay, who can tell when next the work will emerge as a community identifies a need and forms a YMCA as an appropriate response.

Dennis Oliver

November 1995

Page 5

INTRODUCTION

One day in 1844 a small group of English drapery apprentices gathered for prayers after work, and started a social movement which was to spread throughout the world. The group called itself the Young Men’s Christian Association and grew from prayer services to evangelical meetings to lectures, always aiming to improve young men’s spiritual conditions. Between word-of-mouth and the work of founder George Williams, the idea spread to other parts of England and eventually overseas. R.B. Shalders, a London member, emigrated to New Zealand in 1855 and established a YMCA in Auckland, which was followed by Associations in Wellington, Christchurch, Nelson, Dunedin and Invercargill.

The YMCA movement reached Hawke’s Bay at the turn of the century, and quickly became established as a strong community organisation, a profile which has endured to the present day despite the vast social changes of the past hundred years. In the 1890s, the area boasted a thriving agricultural and pastoral economy, and a population of around 15,000 settlers. Wealthy Pakeha landowners and businesspeople enjoyed a middle-class Victorian culture of genteel grandeur, while the majority of Maori lived a traditional lifestyle on the land. Over one hundred years later the Hawke’s Bay community is radically different, yet the YMCA is still an active force in the area. In 1995 the organisation runs forty programmes ranging from employment training to health and fitness to youth work, and employs thirty full-time and twenty-one part-time staff.

In the intervening years the organisation has been destroyed by earthquake and fire, forced to close through lack of funds and alternately praised and condemned for its social policies. The movement has operated in main centres and rural localities, opening and closing facilities according to local needs. Throughout these changes the YMCA has retained community needs and individual development as its priorities for action, and has consistently worked from a basis of Christian values

This book is an attempt to record these stories of continuity and change in the life of the YMCA in Hawke’s Bay. The inevitable constraints of time and resources have limited the depth and breadth of investigations on numerous occasions. There are also many instances where a lack of written records or memories means we know little of the organisation’s activities or people. While every effort has been made to obtain full and accurate information, omissions of names, dates and projects have nevertheless been unavoidable, and many worthy people and events remain unacknowledged.

The book is organised around the three main goals of the international YMCA movement – to develop the body, mind and spirit of members. Two further elements of the organisation in Hawke’s Bay have been significant enough to warrant separate chapters; firstly, the contribution of the YMCA in Hawke’s Bay to its local community, and secondly the people behind the organisation’s activities. It is hoped that this first published record of the YMCA in Hawke’s Bay provides a comprehensive description of the local movement’s development, and will lead to further research on the role of the YMCA in New Zealand’s past.

Page 6

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following individuals and groups have provided valuable assistance and advice during the course of this project:

Manuscripts Section, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Joy Axford, Hawke’s Bay Museum Library.

Bronwyn Dalley, Historical Branch, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington.

Tinaka Mahia-Stewart.

Valerie Tait, National Council of YMCAs of New Zealand.

Napier Public Library.

Oral History Unit, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Companies Office, Department of Justice, Napier.

Ruth Taylor, Hawke’s Bay Herald-Tribune, Hastings.

Hugh at Baytech Computer Services, Hastings.

The staff, Board members and friends, past and present, of the YMCA of Hawke’s Bay.

CHRONOLOGY

1890 YMCA established in Napier, calling itself the “YMCA of Hawke’s Bay”, with 37 inaugural members. Meetings held at Atheneum Hall.

1910 YMCA established in Hastings. Meetings held at Council Chambers.

1911 Hastings YMCA moves to leased building on corner of St. Aubyn Street and Station Street.

1920s Napier YMCA moves into premises upstairs from Murray Roberts & Co., corner of Emerson Street and Marine Parade.

Early 1920s Hastings YMCA operating from Queen Street.

1931 Earthquake severely damages both Napier and Hastings YMCAs. Napier building destroyed, and with no security for mortgage the association was declared bankrupt. Hastings building damaged and sold, and association went into recess with a Trust Fund for re-establishment held by joint Trustees Gordon Roach, Norm Tifford and Sir Edwin Bate.

Early 1950s Hastings YMCA re-established by Ray Whiteman and Guy Baillie.

1955 Camp Opoutama established by Hastings YMCA.

1960 Hastings YMCA stadium built in Railway Road.

1963 Napier Police Youth Club transferred to newly-formed YMCA. Operating from the recently closed Hastings Street School.

1967 Napier YMCA purchased Latham Street property from Hawke’s Bay Milk Treatment Company.

1983 Hastings stadium and hostel sold to Hastings District Council.

1985 Napier Health and Fitness Centre moved from Dickens Street to Latham Street.

1991 Fire at Napier Health and Fitness Centre.

1994 Hastings and Napier YMCAs amalgamated to form YMCA of Hawke’s Bay.

Page 7

Chapter One – The Body

Get out of doors’, ’tis there you’ll find

The better things of heart and mind

Get out beneath some stretch of sky

And watch the white clouds drifting by

And all the petty thoughts will fade

Before the wonders God has made.

– “Camping for Boys”, Hastings YMCA brochure, 1932.

The YMCA is probably best known in Hawke’s Bay for its physical recreation programmes, run either through gymnasiums and stadiums or in the outdoors. As with all YMCA activities, the particular focus of physical recreation programmes has shifted with social trends and current needs. At the turn of the century, the YMCA offered structured classes in gymnastics only, and initiated group camping. In later years, sports clubs proliferated as community needs widened, and camps were further developed. Since the 1970s, physical recreation programmes have diversified still further to accommodate the needs of people of varying abilities and ages. Throughout, however, the goal has been not only to develop and strengthen the body, but also to promote the healthy growth of spirit and mind.

The YMCA’s earliest physical recreation programmes were structured group events, in line with the organised nature of early twentieth-century leisure. From 1910 Hastings YMCA ran a Swimming Club at the Maddison Baths, and from 1912 Hastings YMCA ran gym classes for young men and women in their Station Street premises. The gym classes were particularly popular, and attracted youths and senior high school students from Napier, Hastings and surrounding districts. In a few years numbers grew from a single group of seventeen members to over sixty. The small number of girls were grouped together in a “Ladies’ Class”, while the boys were split into age groups. A full-time physical director was required, as well as the voluntary assistants, and Napier YMCA agreed to share the expense of the wages with Hastings.

With an increased membership, the gymnasium moved to a building on the corner of Market Street and Avenue Road. George Kemp remembers going to gym classes there on Saturday mornings in the mid 1920s;

We would do exercises, lunging and arm stretching, you name it we had it.

We had the springboard, we had the parallel bars, we had the vaulting horse and the rings, and the big mattress to land on. We thought this was marvellous.

These classes were led by Duke (Clarence) Maddox, and his younger brother, Max, assisted by a Mr Spooner. Duke had previously toured New Zealand and Australia as a professional boxer, and was hired as an instructor in 1923 to replace

Page 8

H.L. Firth. Firth had resigned to take up a similar post as physical instructor at the Hamilton YMCA. Ladies’ classes, which had first begun in 1912, also boomed and one of the first female members. Ivy Thompson, became Ladies’ Instructor in 1922.

In the late 1920s the Hastings YMCA gym club performed regular public displays of members’ abilities at the Hastings Municipal Theatre, and George’s group was one of those involved:

Tom, my brother, led the group of boys onto the stage, and we formed ourselves, eventually, after a little bit of a muckup, into a proper line and we did our routine of exercises. Max [Maddoxj, the clown . . . one guy would come along and grab hold of the bar and do his exercises on it, ups and downs and twirling around and straddling it, and Max would come along and make out that he was going to grab it and purposely miss it, and land flat on his tummy on the stage.

Being the smallest of his group, Tom Kemp had some particular roles in the display. Duke Maddox would show his strength by walking about the stage doing his exercises with Tom on his shoulders; and for the finale:

Photo caption –

“Ladies’ class at the Hastings YMCA gymnasium, 1912”.

Top row: Doris Corban, Vi Pitt, Alice Corban, – , Leila Pill, Chloe Bush.

Second row: Jean Thompson, – , Ivy Thompson, Mr Buchanan , Elsie Pitt, Amy Watts, Miss Read.

Third row: Bunty Mitchell, Bessy Mitchell, – Horton, – Reed.

– Reproduced with the permission of the Hastings District Library.

Page 9

There was a pyramid of six or seven [boys] high and I [Tom] was at the top. The whole thing would dismantle, tumble, tumble, tumble, til we all finished up in a square at the bottom. It must have been quite spectacular.

With the arrival of Eric Price as Hastings YMCA director in 1929, the boys’ clubs, numbering 120 boys in all, were rearranged and renamed. Each “natural group” was from the same school – Parkvale, Mahora, West – or from the same work area, such as the Newsboys. Tom’s group became the Tuxis Boys. At the end of each gymnastics session, the boys would stop for prayers and devotions and sing the Tuxis song:

Tuxis boys, up and on

Up to victory, on to fame

Watch your step and play the game

Tuxis boys, spell that noise

T- U-X-I-S, Tuxis, Tuxis boys

George Kemp remembers, too, the Bible verse his group of boys recited –

“Luke 2 and 52: Jesus increased in wisdom and in stature, and in favour with God and Man”. This was repeated after every devotion, following which the boys would have a mug of coffee and half a cabin lunch biscuit. The cabin biscuits were renowned for their hardness, “a little better than a dog biscuit”, as George puts it, but were nevertheless “gorged down marvellously”.

Organised YMCA camps also originated in these early years as a place for physical fun and growth. Hastings YMCA ran camps at Clive Grange from 1918, with members Fred Musson, Bert Heaton and Flewellyn King serving as the first leaders. Groups of eighteen to twenty boys from the surrounding districts, aged from twelve years, were taken out for up to six days. Camp programmes included explorations of the local area, hikes to Cape Kidnappers, and outdoor skills. In the 1920s YMCA camps were expanded to cover both summer and Easter holidays, and fifty to sixty boys each year spent up to ten days at Te Mata Peak and, from 1929, Waipunga, Eskdale. The Eskdale campsite was on the property of YMCA member D. Yule, and consisted of permanent sleeping quarters, a dining-room and cook house, playing fields and a swimming hole. The swimming hole was not only for swimming though – it was the compulsory early morning bath for campers, despite the often bitter cold of the Esk River.

Campers were warned to “Wear only Old Clothes!” and instructed to pack their gear in a sugar sack. Cycling camps were popular, with groups sometimes cycling to Waipunga, twelve miles from Napier, exploring the area by bicycle, and cycling home. Camp food was plentiful, beginning with huge cooked breakfasts of porridge, chops, eggs and sausages, and sometimes supplemented by crayfish caught by the boys with reeds. The camp programme was always a full one, including climbing, hiking, swimming, cricket, first-aid lessons and farm work for the Yules. Small parties of boys left the main camp, with an adult leader, to spend a night

Page 10

under the stars, and day or overnight trips were made to nearby attractions. Popular trips included Tongoio Falls (eleven miles distant), Darkey’s Spur, Lake Tutira, Waipatiki Beach and Rocky Basin. Tom and George Kemp recall one memorable trek to White Pine Bush:

It took all day, up hill and down dale, and we got there about nightfall. The highlight of going was picking blackberries, and we ate what we could on the way. There was one very long-legged guy from Mahora, Trevor Watts, and apparently he knew nothing about hills. One thing you don’t do on the hills is run downhill, unless you’re completely controlled; well, he had no idea about this. He had very long legs, and going down the hill he just got faster and faster, until he was a blur, completely out of control, going flat out. We could see it coming – down the bottom of the hill was a blackberry bush about half the size of a house, and he had no show of stopping. He didn’t have many clothes on, and he went straight into the bush. It took a long, long while to get him out, with hands and an odd knife, and we had to get sticks. He was really torn all over, and I think they had to get him to hospital. There was only one way to describe him – a bloody black mess”.

Sid Coles remembers a similar overnight trek to Te Puhoe [Pohue?]:

It was a mighty long hike. I remember when we got to lunchtime, one of the things we had was a leg of mutton, and we had a bottle of milk. When we opened the mutton to have a slice each, it was absolutely crawling! We really didn’t have a lot of tucker. It was really crawling and we had to throw it away. The milk, with all the travelling, well all you could see was a little knob of butter.

For some boys, the ghost stories told round the campfire were particularly

Photo caption – YMCA camps were based at this hay barn at Waipunga, Eskdale, from 1929 to 1932. Boys slept on straw palliasses upstairs in the barn, and bathed in a swimming hole behind the poplar trees.

Page 11

memorable. Tom Kemp remembers a story being told of a phantom horserider who rode across the bridge beside the Waipunga woolshed every night. At the moment this story was told, an accomplice of the storyteller would ride a horse across the bridge behind the campfire, to the shock, surprise and general fear of the young campers. The stories apparently “spooked” some Hastings parents too, as Len Webb recalls:

I was never allowed to go [to camp]. There were horrific stories that came out about what went on there, nothing immoral or anything, but ghosts parading around the place. Something in that place was meant to be haunted. As a youngster, when I went home and told the family about these ghost stories and how kids got frightened of it all, well my mother wouldn’t let her little darling go to a camp.

In addition to physical fun, early YMCA camping was also a place for educational and spiritual development. While the summer camps were run by “the Director”, usually Eric Price, and two young leaders, the Easter camp was run entirely by the boys themselves. The youths chose the campsite, planned the programme, budgeted for expenses and distributed the surplus of funds after camp. In addition to these lessons in organisation and management, Waipunga camps were intended to be thoroughly Christian camps. Daily chapel services were included in the programme, the New Testament appeared on the boys’ kit list, and the purpose of the camp was set out as “helping boys discover the better way – His way – for every activity.” This goal was frequently attained – the Hastings YMCA Annual Report of 1931 recorded that “eleven decisions to live for Christ were made in this period [of the Summer Camp] by eleven boys who would not be satisfied with less than the best.” As the information brochures proclaimed, “Camping and Character Go Hand in Hand At Waipunga”, and Eric Price, Hastings YMCA Secretary, described camping as a method through which boys are coming to love nature, to learn afresh how to live simply and take care of oneself, to experience the skill of friendship and comradeship, and to listen to the voice of God as He speaks to them in the quiet of the out-of-doors.

After World War II, twenty five years after the destruction of the YMCAs of Hawkes Bay in the 1931 earthquake, the movement was reformed and physical recreation programmes were amongst the first to be resurrected. During this period, sports were largely organised as individual clubs in response to community demands. Buildings and facilities were upgraded as numbers and needs grew, and YMCA camps also expanded further with the development of Camp Opoutama at Mahia.

Numerous YMCA clubs opened, operated, and sometimes closed, in the immediate post-war years. In Hastings, Ray Whiteman restarted the YMCA with a gymnastics club and youth group. Ross Duncan, who later became involved with the YMCA as an adult, remembers going to gymnastics at the Y:

Page 12

We would meet regularly, and I’m pretty sure it was a Friday night, because I have vivid memories of going into the Wesley Hall in Hastings Street and getting really hot and thirsty and at the end of the night along with chaps like Graeme Richardson, Bruce Jans and Warren Thom and some of those who were members at that time going down to the Excel milkbar and having a milkshake, and that was a regular Friday night activity. I guess that was where my love for gymnastics was born.

Representatives of the Hastings gymnastics group later travelled to compete at national YMCA Older Boys’ Tournaments. These tournaments also involved debating, volleyball and table tennis teams and were ideal places for boys to enjoy physical and social recreation simultaneously. Club member Graeme Richardson recalls the Hastings Club’s trips to Christchurch and Wellington, when the boys would travel by train and ferry, be billeted by locals and marvel at such local wonders as Canterbury’s mid-winter frosts. Club members also performed public displays of gymnastics on regular occasions, including the annual Gymnastic Display held in the Hastings YMCA Stadium. These programmes provided the public with a valuable insight into the activities of the YMCA, with children from five years old demonstrating folk dances, pyramids, rhythmical work and apparatus use.

In Napier, the newly-formed YMCA carried on the gymnastics classes run by the Police Youth Club. The success of the group was partly due to the instruction of Rex Smith, General Secretary of the Napier YMCA.

Rex had taught gymnastics at Lower Hutt YMCA and at Linton Army Camp, and his skills and enthusiasm helped create a large and popular club. Members travelled to National Older Boys and Older Girls Tournaments, and a special Silver Squad of children wanting individual, specialised coaching was formed. Doug Fraser, whose children were club members, became involved with the gymnastics group as voluntary assistant. Doug also served on the Napier YMCA

The Napier YMCA gymnastics group first met at the Hastings Street School as the Police and Citizens Youth Club. Here Rex Smith, Napier’s General Secretary, coaches the group in the school hall in the early 1960s. – Photograph courtesy of Rex Smith.

Page 13

Board, as Executive Director from 1975-1976, and in 1991 was made a Life Member of the Napier YMCA. A host of other voluntary assistants helped keep the clubs running with support, leadership and administration, including girls’ gymnastics instructors Elizabeth Gollop and Miss J. Wright. In 1968 the club moved from its original site at the old Hastings Street School to a new, larger YMCA facility on the site of the old milk treatment station in Latham Street. With more space the club boomed, increasing from 145 members in 1966 to 300 in 1967. Classes were also run from mid-1967 at the Taradale Rugby Club gymnasium, where a further 320 children were involved. Some of the club’s members were also regularly winning awards at the Hawke’s Bay Gymnastics Championships.

Trampolining was a popular part of the club, and later operated separately from the gymnasts. One especially talented member went on to be a New Zealand Trampolining Champion. Cyril Whitaker’s daughter was one of the YMCA trampoliners in Hastings, and Cyril, like Doug in Napier, became involved with the YMCA through his children. Cyril has served on the Hastings YMCA Board, as Hastings’ President, and in 1995 is a Hawke’s Bay YMCA Board member. The gymnastics clubs declined in the mid-1970s as schools began teaching gymnastics and the need for YMCA clubs disappeared. Rex Smith also sees the advent of televised trampolining as a blow to the previously popular trampolining and gymnastic displays provided by the club at schools and carnivals.

While Napier’s youth were enjoying gymnastics and trampolining in the Hastings Street School hall, the school’s classrooms were used for judo, wrestling and boxing lessons. The Judo Club, under Bill Madore’s guidance, was particularly active. The group had begun in Richard Bayliss’ Taradale garage in 1954 under the instruction of Kurt Dobrew, and as numbers grew it had moved around several temporary premises. When Bill Madore, the club’s Secretary/ Treasurer, joined the Napier YMCA Board at its inaugural meeting, he recognised the potential for cooperative growth. The Y wanted to encourage youth sports, and the Judo Club needed a more permanent support base, so the Judo Club affiliated with the YMCA and moved into the Hastings Street School rooms. At Hastings

A human pyramid, the finale of a gymnastics display by Hastings YMCA at a Pipe Band display, Easter 1966. – Reproduced from Hawke’s Bay Photo News, May 1966.

Page 14

Street the club was able to expand, and taught up to forty members. Bill Madore recalls one early member particularly well:

We had one chap who came along, he was still at school, and he stuttered very badly. He came and took up judo and just with the self-confidence he had from judo, he lost his stuttering. Six months after he started he’d improved so much that his mother came along and thanked the club for helping him.

The Napier Club also hosted two visiting Japanese judo experts, and when Japanese ships were in port Bill Madore and Frank Price, who was fluent in Japanese, arranged for crew members to come ashore and practise with the club. In 1957, the North Island Judo Championships were held at Napier, again largely due to Bill Madore’s organisation. Also at Hastings Street, Trevor Reed tutored wrestling, and T. Halpin coached boxing.

Both these teams made regular visits to other similar clubs, and entered members in regional competitions with some success. A highlight of these three YMCA groups’ early years was an invitation in the early 1960s to visit the Sydney Police Youth Club. Twenty eight youths representing judo, wrestling and boxing, and accompanied by Ray Frederickson of the Judo Club and Doug Fraser of the gymnastics group, were hosted by the Sydney club. The group stayed in the Police Youth Club

Photo captions –

The Hastings YMCA Trampolining Club gave public displays at events such as this Blossom Parade in 1967. Here Grant Bridges is on the trampoline while the public waits for their turn – one shillings per 1½ minute bounce.

Junior wrestlers Barry Patchett and Stephen Ulyatt in action, watched by the rest of the junior class. – Reproduced from The Hawke’s Bay Photo News, March 1956.

Page 15

dormitories, enjoyed sports matches with the Youth Club teams under the banner of “The Trans-Tasman Mat Games”, and had several days sightseeing around Sydney before returning to Napier. The Sydney group later made a reciprocal visit to Hawke’s Bay and were taken on rural activities such as sheep-shearing and top-dressing.

Both Napier and Hastings YMCAs found after a few years that their physical recreation facilities were unable to meet the demand from local youth, and both moved into larger premises and new programmes in the 1960s. The Napier YMCA acquired a fully functioning fitness studio through the work of supportive local men. A group of Napier businessmen purchased the failed Dickens Street Silhouette Club from its receivers in 1965, with the belief that such a facility’ was needed by the local community and should not be lost. Calling themselves the 325 Club, these men estimated that 325 members were required to keep the Health Studio solvent. Local businessmen Pat Magill, Doug Fraser, Gary Crichton, Brian Buchanan, Lloyd Duckworth and others canvassed their friends and colleagues for prospective members. One of the original Silhouette Club owners, Graeme Gardiner, joined as a subscriber and instructor, and later became involved with the Napier YMCA itself. In 1995 Graeme is an active Board member for the Hawke’s Bay YMCA, and has served the YMCA for many years. Harold Beer, who is still a keen YMCA gym member in 1995, was also one of the 325 Club. Harold remembers Pat Magill, one of his business clients, approaching him for a subscription.

Pat came around, roped me in on the 31st March 1966, coming in to where I was working and saying to me, “Harold, Silhouette’s gone bung, we’re going to start a 325 Club and you’re always selling me something, so sign here” So I signed up, one of the best things I ever did in my life.

Under the management of the 325 Club, the Dickens Street Studio cleared its debts within twelve months, but soon began to feel that stronger backing was required for the business to continue. Members such as Doug Fraser, who were also involved with the YMCA, suggested that the Club be gifted to the Napier YMCA as a going concern, which it was in 1967. Initially the YMCA Board did not want to be involved with such a potentially insecure undertaking, and declined the offer. However, following negotiations, the YMCA Board agreed to take over the running of the 325 Club provided that the Club guarantee any losses in its first twelve months. In the event, the Club returned good profits and was able to transfer sums of money to the YMCA on several occasions.

In 1967, the Napier YMCA Board purchased a four acre section in Latham Street from the Hawke’s Bay Milk Treatment Company. The existing structure consisted of a solid concrete building with several cool storage rooms and a loading platform, and considerable extensions were required. The original plans for rebuilding were drawn by a Mr J.W. Ogg, a friend of American YMCA man and professional fundraiser Hal Lucas. Mr Ogg had previously been a member of the

Page 16

North American YMCA Building Advisory Service, and devised a three-stage plan of building. In its entirety, the project included a chapel, cafeteria, squash courts, auditorium, handicraft rooms, youth lounge and a 22-bed hostel, although none of these were actually erected.

Instead, a temporary gymnasium was built around the existing Milk Company cool store. The YMCA provided materials, Bill Madore and Les Dobson co-ordinated a pool of voluntary labour, and a hall with separate judo rooms was eventually built. Bill remembers the work involved in building the judo rooms, which was done largely by club members and supporters:

Members’ wives used to down there during the week while their husbands were working, with their hammer and nails. There was always someone there to show them what to do. The wives put a lot of work into that building, perhaps more than the men because they had more time.

Club members and builders Peter Chambers and Peter Cavill provided their professional expertise, while others such as Ishpel Strandle and Barry Richardson provided the labour.

Also in the 1960s, the Hastings YMCA moved into a house in Railway Road and later built a stadium on the section. The house had belonged to local G.P. Dr Moore, and Graeme Richardson, a member of the YMCA youth group at the time, remembers the building when it was first purchased by the YMCA:

It was quite fascinating, there were all these rooms, and little handbasins in all the rooms. There were lots of stories about what used to go on there, and where the abortions went on. The rooms were full of old magazines and newspapers, the place was filthy dirty. You didn’t like to go in there,

Photo caption – One of the original plans for the YMCA building on Latham Street. This complex included a chapel, squash courts, hostel, and youth lounge, none of which were actually constructed.

Page 17

it was all these rooms filled with newspapers and old furniture, and incredibly dirty.

After many days of cleaning, and some building alterations, the main area of the house was used for gymnastics. An asphalt basketball court was laid behind the house; for some local youth this was their first experience of the new game, basketball. The Hastings YMCA Board built a sports stadium on the same site in the early 1960s. George Curtis, a Board member at the time, remembers the initial design of the building as “very elaborate, with a great domed roof. This plan was eventually abandoned due to the excessive building costs involved; George remembers that the drawings themselves had cost £3,000. The stadium was redesigned, and opened in 1963, although it was “pretty stark” to begin with. It was largely built of concrete block, supplied at a reduced cost, along with construction advice, by Firth Concrete Ltd. In later years a tongue-and-groove matai floor was laid at the cost of £4,000, followed by seating for 500 spectators and an ablution block.

These new premises enabled new YMCA clubs to open, and older ones to expand. In Napier, Rex Smith began to tutor fencing for a small but enthusiastic group. Hastings members participated on alternate weeks, and in 1968 merged to form a joint Hastings-Napier Fencing Club.

The existing Napier YMCA Judo Club boomed, and with its own rooms at Latham Street and new classes at Taradale and Greenmeadows attracted an additional 100 members in 1967-68. Several went on to success at the Hawke’s Bay Championships, and an adult member, David Christie, represented New Zealand in International Judo Competitions. The club made regular visits to judo groups, in Palmerston North, Wanganui, New Plymouth, Taupo, Wairoa, Gisborne, Waipukurau, Waipawa and Dannevirke, and ran a training weekend every two months for all East Coast clubs. These trips were organised by club secretary Bill Madore, who was also East Coast Area Director for the New Zealand Judo Federation, and was responsible for overseeing all the judo clubs in the area. The visits were usually weekend events, and always reciprocal, with the visited club later coming to Napier and being billeted

Page 18

there; as Bill says, “quite big friendships were built up”, both between adult officials and amongst the younger members. Although classes were segregated, the club was open to males and females, and by the late 1960s girls and women made up approximately half the group’s membership. Initially, women were taught a more “graceful” and technique-oriented style of judo the men’s competition-style, than but women tended to prefer the male style and the women’s section was eventually disbanded in favour of mixed classes. Bill Madore continued to oversee the club as Senior Instructor and Secretary until 1968, with Bill Wickstead and Brian Davies assisting him. Mrs E. Crosbie tutored the women’s section, and at Greenmeadows John and Ulia Hadfield and Richard Bayliss, one of the club’s founding members, provided coaching.

YMCA volleyball and basketball teams, relatively new sports, were also begun in the 1960s. These were strong clubs, particularly after the building of the Hastings stadium provided the basketball players with an indoor venue. They had previously been playing on an asphalt court on the Railway Road section. Both Napier and Hastings YMCAs had girls and boys teams, under the leadership of John Hampson [Hampson] and Fred Chu. In 1964 Hastings YMCA hosted the North Island Indoor Basketball Tournament.

The YMCA Basketball Club eventually moved out of the stadium as a result of a disagreement over rental continued elsewhere fees to and operate under a different name.

A third popular and strong group was the

Photo captions –

A fencing demonstration, part of the Napier YMCA^s end-of-year Gymnastics Display at the Majestic Hall, December 1966. The fighters were Lewis Harrison of Hastings (facing the camera) and John Joanes of Napier. Reproduced from The Hawke’s Bay Photo News, December 1966.

An early photograph of the Napier YMCA Judo Club showing three of the founding members. From right in the front row are Bill Madore, Ray Frederickson and Richard Bayliss. – Photograph courtesy of Bill Madore.

Page 19

Hastings YMCA Badminton Club which opened in the early 1960s. Bill Cummins, who had already started a club at Colenso High School in Napier, started the Hastings group at the stadium even before the wooden floor was laid. The asphalt was painted with the court markings and played on regardless. Bill and his wife Trish, also a keen badminton player, were the mainstays of the club, and worked hard to develop the club. Together, they ran training weekends for young badminton players from around the country. The players would sleep in the house at Railway Road, with Trish and Bill as chaperones. Trish remembers that the girls slept upstairs and the boys downstairs, and “there were always footsteps running up and down the stairs at night”. Peg Thorn, one of the camp caterers, came in to do the cooking for these weekends. Bill and Trish also organised inter-club tournaments with those Hastings clubs which had not amalgamated with the YMCA group. The Hastings club travelled afield further too, and made regular exchange trips to clubs around the Wairarapa, Manawatu, Mangakino and Taupo. Bill later became involved at a national level, and served a term as President of the New Zealand Badminton Council, as well as organising two New Zealand Championship tournaments and an international New Zealand-Australia tournament in Hastings. Under Bill and Trish’s guidance the Hastings YMCA stadium became known as the centre of badminton in the central North Island, and indeed still is a strong club in 1995.

In addition to these clubs, the YMCAs also ran general “keep-fit” programmes in Napier and Hastings. Napier’s Dickens Street Health Studio catered for over 400 members in 1967, providing all the standard fitness equipment and classes to members. Facilities included an exercise room, steam room, sauna bath, sunroom and massages, and sessions were segregated, allowing men-only and

Photo caption –

The Hastings YMCA Indoor Basketball team the “Leopard LLs”, 1970.

Back row: (L-R) G.T. Willis, B. Godber, .W. Nash, I.L. Hampson.

Front row: (L-R) C.W. Daly, P.M. Tegg, F. Chu (Coach), J.O. Hampson (President), B.R. Hooker (Captain).

Page 20

women-only times. Originally, the Studio was only open to members who had joined and paid for twelve months’ membership. However Board member Dulcie Malcolm argued that women were less likely than men to have the funds for a twelve month membership, and suggested that the Studio also offer casual memberships and per-visit charges. This idea was a great success, with women’s gym memberships booming to over 200 within a few months. Dulcie Malcolm was also a strong force behind the introduction of women’s yoga, ante-natal and post-natal classes at the Health Studio in 1967. Keep Fit classes for women were also taught at the Latham Street gymnasium. Classes were taught by Mrs H. Lloyd and covered a variety of exercises; although the General Secretary reported in 1964 that “strangely enough, it is the trampoline which is the main attraction” of the Married Women’s class. In Hastings, Fred Chu and Don Nordhaus taught fitness classes at the YMCA stadium. These classes included jogging, calisthenics, trampolining, gymnastics, stretching exercises and general fitness and aerobic work. Both evening classes and morning classes, where children were welcome, were held. A journalist from the Hawkers Bay Herald-Tribune visited the daytime class in August 1965 and reported:

Most of the women had young families and felt that they didn’t keep fit enough just doing the house work. Quite a number had been involved in outdoor sports before being married and wanted to keep active. Others simply wanted to lose weight.

Saturday mornings were also busy times at the stadium, when up to 150 children attended gymnastics sessions. A “round-robin” circuit was set up, with the children rotating around activities such as tumbling, running and trampolining. Few schools owned stadiums at this time and for many children the YMCA gymnasium was the only place for them to enjoy indoor gymnastics activities.

YMCA camping flourished in the post-World War II years also, perhaps partly as a natural result of the post-war baby boom. Hastings YMCA took a lease on land at Opoutama, near the Mahia Peninsula, from the Department of Conservation in 1954 and developed a campsite there for the youth of Hawke’s Bay. Bill Cummins, later a Hastings YMCA member, remembers taking a group of Gisborne YMCA

Photo caption – The Hastings YMCA Orbits team, pictured after the North Island Indoor Basketball Tournament held at Hastings in October 1964. The players are: Bernice Smith, Margaret Morris, Lynn Robinson, Ngaire Tinning, Heather Flack and Yvonne Cosford.

Page 21

children camping at Opoutama in 1954 while he was living in the town:

There was nothing there. There was a trench to put a fire in, and that was where you cooked, and you had old tin walls around a space and that was your toilet.

Ray Whitemans son, Murray, recalls the early days of Camp Opoutama;

“Camp Opoutama was begun the first year we were at Hastings. We used the area near the Blue Bay Park Motor Camp to begin with until the present camp site was found. The camps were an amazing achievement.

Each year an advance guard party would arrive at camp to prepare for the arrival of the first group for Campers. For many years the camp was run prior to Christmas and for all of January and consisted of ten day spells with 150 children being the normal number in camp. They all used to arrive from either Hawkes Bay or Gisborne by railcar and arrivals and departures occurred on the same day. The boys walked to camp from the railway station but their luggage was taken on a truck driven by Mr Todd. “Old Todd’s Truck,” was sung at camp many times. He also helped get the gear from overnight camps at Morere where the boys made bivouacs and generally learned to rough it outdoors, swim, abseiling and trek, then hot pools before heading back to Camp Opoutama. You may be aware that all camping was done under tents for the whole ten years that my father ran the camp. The only buildings on site were the cookhouse, food storage shed and eventually, the directors cabin apart from the structures built for pit toilets. Camp activities were as follows, Archery, rivalry, commando course, trampoline, swimming, boating, surf skiing, fishing, morning devotions at a chapel under the trees, tennis quoits and other similar activities. A day trip to Mahia and back by foot was also a firm favourite.

I can remember one year when it rained for the entire 10 days that one group of boys were in camp. As they were all under canvas we had to use the local school hall for sleeping eating and general activities which included many movies. A ten day camp for girls was trialed after a number of years, and these proved to be a great success. I can recall an amusing situation on the first night after all the girls camp was sent to bed that an orderly procession of lights could be seen coming down from the tents. Upon investigation it was discovered that they were all coming to have a wash. They were soon put right on that as water was a scarce commodity at camp.”

Soon after, George Curtis and a team of voluntary builders began the development of the camp and erected sleeping shelters, a dining hall, confidence course, ablutions and toilet blocks. Fred Chu, of Hastings YMCA, invited Napier’s Rex Smith to assist in camp work, and together with numerous parents, members

Page 22

and staff who volunteered their time and expertise, a strong and popular camp was established. Cyril Whitaker, Randal Hart, Ray Whiteman, John Harris, David Bullock and Elizabeth Gollop were some of the many who also contributed their time. Leaders were mainly young male teachers to begin with, and camp staff was generally wholly male. Local residents helped with camps too; a Mr Todd voluntarily appointed himself caretaker, and would bring in the milk, meet the train and clear away rubbish; George Foster at the local garage repaired the camp equipment and vehicles. Camping was also perhaps one of the first YMCA activites to involve a substantial number of women participants working alongside men, such as nurses Ngaire Bone and Fiona Whitaker, and cooks Nell Drown and Peg Thom (or “Thommie”). These women provided often crucial services, as well as creating a “family” atmosphere within the camp. Rex Smith remembers that a homesick young boy would be sent to the camp kitchen “for chores” on the understanding that the cooks would “make a fuss of him” and he would soon “come right”. Indeed, Camp Opoutama was often literally a “family camp”, as whole families would sometimes be in residence together. Cyril Whitaker, a Board member, and his wife Fiona, camp nurse, would on occasion have all five of their children in camp simultaneously as leaders, helpers and campers. One of the Whitaker daughters even met her future husband at Camp Opoutama when they shared camp leadership responsibilities one summer.

Camp groups were split into Seniors and Juniors, Boys and Girls, with Seniors staying ten days and Juniors seven days. Programme activities were firmly centred on the outdoors, such as archery, fencing, hiking, climbing, outdoor skills and swimming. Overnight out-camps at Mourere were also popular. Campers would sleep “rough” in a bush bivouac, and cook their own meals from provided rations. Other treks included waterfalls, pools, caves and hot springs and Maumakai Mountain. Spiritual development was not neglected, though, and camp leaders held daily prayer meetings for all campers. The post-war camps also saw the establishment of special Camp Opoutama traditions, many of which endured for some time. The campfire ghost stories of Ray (“Soapy”) Whiteman were particularly memorable, as was the special campfire on the last night

Photo caption – A tent group – Opoutama 1956.

Page 23

of camp, as Fiona and Cyril Whitaker remember:

There was one campfire that had a special place, you had to go there through the pines in a special way, and that was kept for the last campfire. They’d all go there, and the campfire would all be set. They told the story of the ghost of a little lad who went to camp, and they called on the ghost to come and light the campfire. Everybody would be sitting round in a circle, the campfire had been set, all ready to go, nobody was near it, and at a certain time all of a sudden this wisp of smoke came up out of the fire and it started to go. They’d been sitting there for an hour or more! It was a case of Candy’s Crystals and paraffin in a tube, and the person telling of the story just pulled the cord and let the Candy’s Crystals drop into the paraffin and away it goes!

Since the 1970s, Hawke’s Bay YMCA’s concept of physical recreation has broadened to include groups not previously active in the predominantly male, able-bodied YMCA. The special needs of women, the disabled, children and the aged have increasingly been catered for in addition to main-stream programmes, and smaller facilities have replaced the stadiums and gymnasiums.

The YMCAs of Hawke’s Bay have trialled and adopted a variety of programmes especially designed to fill the recreation physical needs of specific groups. In the early 1970s women’s self defence classes were taught with some success, and ante-natal and post-natal exercise classes have been run intermittently. The pregnancy classes held in 1990 involved a no-impact exercise class to music, followed by an informal discussion group with invited childcare speakers. These classes, run by midwives and a physiotherapist, were designed to maintain fitness, strength and flexibility for expectant women. The Napier Health and Fitness Centre also recognised the needs of mothers in its decision to provide child-minding facilities during aerobics classes, with fully-qualified supervisors on the staff. The YMCA has also occasionally offered physical recreation programmes tailored to specific groups such as intellectually handicapped youths in the 1970s, A.C.C. rehabilitation clients in 1988 and cardiac patients since 1992. Jim Thorne, programme director at Napier YMCA, was particularly active with special needs

Photo caption – Around the campfire.

Page 24

children in the mid-1970s, teaching members of Marewa Special School, Disabled Workshop, Fairhaven School and the Intellectually Handicapped Children Society weekly for several years. Pre-schoolers were first invited into the YMCA in the early 1970s, with the “Tiny-Ys” programme. The Napier Tiny-Ys group began with over 100 children aged between 2 and 5 years, but it is not clear exactly how long the group operated before closing. A “kindergym” was also run by Philip Ferrier of the Hastings YMCA at Flaxmere Church Centre from 1976. Philip constructed the necessary equipment himself, including a mini-vaulting box and mini-beam, and the group attracted up to 35 children each week. A similar group was also run at Havelock North from 1977. In 1995, YMCA youth worker Debi Robinson revived pre-school gym classes and runs twice-weekly “Ys Gym” sessions for fifteen to twenty pre-school children.

The 1970s was also a boom time for YMCA sports clubs. Ian Johnson co-ordinated canoeing groups in both Hastings and Napier, taking groups on weekend expeditions during 1977 and 1978. In Napier, brothers Bruce and Derek Campbell led a badminton club, and Tong Too instructed a Tae Kwon Doe club. A judo club, under Mrs Davies, a trampoline group (with Rowan Shields and Simon Daly) and a tennis club also operated from Napier’s Latham Street premises. The Napier YMCA wrestling club continued to operate with the guidance of father-and-son Trevor and Kevin Reid, although by 1978 the club had outgrown the YMCA facilities and shifted to a larger venue. The YMCA boxing club was the only one in Napier, and grew to forty members by the late 1970s. In Hastings, Brian Lee ran a weightlifting club which grew to over fifty members. This wide range of clubs offered a greater variety of recreational options to the Hawke’s Bay community than in previous decades, and enabled a greater diversity of people to become involved in YMCA activities.

Physical recreation programmes have traditionally neglected the needs of older people; however the national YMCA Ys Walking programme attempted to fill this gap. Begun in Hawke’s Bay in 1983, the Hastings group foundered and closed within a few years. The Napier group, however, has had a particularly dedicated commitee [committee] and instructors, and is still active in 1995 with up to twenty six regular walkers, all over the age of fifty. Ys Walking involves twice weekly walking groups and exercise programmes, and occasional half-marathon events. The aim is to provide low impact aerobic exercise, develop an active lifestyle for older people and introduce a new interest for the retired. Or, as a local promotional pamphlet put it:

WHAT IS ALL THIS Y’S WALKING ABOUT?

Men and women mostly on the high side of 50 pounding of the pavements of Napier’s reserves and streets! Striding it out!z

IT’S ABOUT people beginning to feel good, losing weight, lowering blood pressure, feeling relaxed, having fun, enjoying the sociability.

The Napier group also has a Sunday Club which makes longer walks and hikes, and

Page 25

the group’s committee organises social functions during the year. Much of the success of the group is due to its co-ordinator Doug Fraser, who resigned as Instructor in 1993. The strong committee led by Bill Creek and Paul Rowling have continued to lead the group.

The YMCA interest in the value of walking as physical recreation is also apparent in the formation of the Napier YMCA Tramping Club. The idea for a club was first discussed by Doug Fraser and Pat Magill while on the 1971 Napier-Taupo sponsored walk to raise funds for the YMCA’s “Pub With No Beer” project. Both Doug and Pat felt that the public of Napier would benefit from exploring the natural attractions of their surrounding area, and resolved to begin by offering an organised walk around Lake Waikaremoana. After much planning and help from many people, the walk took place in January 1974, as Doug Fraser remembers;

107 walkers ranging in ages from 70 to 7 years met at Mokau Landing where tents and food were ready to greet the participants. Each day for four days the walkers travelled a section of the Lake walk carrying lunch and day packs. Willing helpers dismantled camp sites and transported them to the day’s destination and when the weary campers arrived tents and food were already waiting for them.

The event was such a success that during the walk participants suggested that the walk become an annual event to enable Napier people to enjoy the bush and mountains. Although Hastings people had a well-established Heretaunga Tramping Club, Napier had no similar group to organise such an event. So, as Doug reports,

Y’s Walking Group outside Napier YMCA and Michaels Place, Latham Street.

From left: Bill Creek, ?, Roz Jones, ?, ? , Bette Creek, Eileen Perry, ? , ? , Doug Eraser. – Photograph courtesy of Bill Creek.

Page 26

the embryo of the Napier YMCA Tramping Club came into being, around the campfire, in the stillness of the Urawera [Urewera] bush, with the sound of long tail cuckoos screeching their song and the moonlight glistening on the “Sea of Rippling Waters”.

On the group’s return to Napier, the idea of a Tramping Club was put to the YMCA Board and the Club duly formed. Its first office-holders were Doug Fraser, Ross Keating, Merhyl Anderson and Tony Des Landes, with the assistance of Alan Lee, Christine Sinclair and Ed Smith. The Club’s first tramp was a day trip to Kaweka J, the highest point in Hawke’s Bay, on 5 October 1974; every following year on the club’s anniversary members have re-enacted the same walk. The Waikaremoana walk also became an annual event, although in some years, such as 1975, the event was expanded to a family camp with day trips from Mokau Landing. The club operated successfully in association with the YMCA for some years, enjoying social events, educational lectures and regular day, weekend and longer tramps, all of which Harold Beer faithfully recorded in the club logbook. Impressions of one of the earliest tramps, a three-day trip into the Urewera National Park led by Doug Fraser, were reported by party members in the first club newsletter in 1974:

Some glorious impromptu swims in waterfalls and river (even one by our leader); lots of fun negotiating upstream, narrow difficult gorge complete with waterfall; dramatic readings from Jonathan Livingstone Seagull; those delightful little orange huts appearing through the foliage, a death defying crossing of a flooded river by swing bridge, and on a more earthy note “The Loo with a View” – best view in the Ureweras!

The importance of junior members was always acknowledged, and youth took an active part in the running of the club. In 1980 the club formally broke away from the Napier YMCA, and continued to operate as the Napier Tramping Club.

The majority of these post-1970s YMCA physical recreation programmes have been centred In Napier, as the Hastings YMCA moved away from physical recreation in the early 1980s. The Napier programmes were shifted from Dickens Street to the YMCA’s Latham Street building in 1985, but have continued in a similar manner. The shift was a cost-cutting measure following the financial burden of the Pub With No Beer project, and aimed to utilise existing YMCA space and remove rental costs from the Studio budget. In Hastings, the Railway Road stadium was under-utilised, with only two YMCA groups, basketball and badminton, using the facility on a regular basis. Outside groups rented the building for the remainder of the time, relegating the YMCA to the role of “a property developer”, as Dennis Oliver described it. The stadium also required extensive, costly maintenance work that the debt-ridden Hastings YMCA could not afford. The Hastings Board, working with Dennis Oliver who was then the National YMCA Council’s Management Consultant in Hastings, refocused the organisation towards training

Page 27

and education, and the stadium became superfluous to the Association. After several months’ negotiation, the Hastings City Council purchased the building for $580,000 in February 1983. The Board and the public had some initial unease regarding selling a facility that the community had contributed to financially for many years. However, the burden of debt on the Association was so huge that the sale came to be seen as helping the people of Hastings, by returning the YMCA to an economically viable and efficient organisation capable of serving the needs of its community. The proceeds of the stadium sale were sufficient to pay off the Hastings YMCA’s considerable debts, and to purchase smaller properties more appropriate to the Association’s new direction.

Since the 1970s YMCA camping has undergone few changes and continues to grow and strengthen. Camps are no longer segregated, and places are reserved especially for underprivileged children who are sponsored by local service groups to attend. Camps have been held at Waikaremoana and on the property of Darcy Wareham at Awapawanui in addition to the Opoutama site. New activities have been introduced to camp programmes, often through the generosity of service and community groups. In 1990 a fleet of Optimist yachts were donated to the camp by the Napier Lions Club and the Havelock North Rotary, at the cost of more than $10,000. The latest camp project is Dennis Oliver’s plan to purchase and run a YMCA train to take campers to Opoutama. Since the 1988 Cyclone Bola disaster destroyed part of the East Coast railway line, the passenger rail service has been discontinued and campers have travelled by road; a much less enjoyable and more expensive means of travel than the train. As of 1995, the project has involved the purchase and conversion by volunteers of two guard’s vans for passengers, and negotiations continue for the purchase of two further units.

The emphasis of the YMCA Hawke’s Bay on the physical development of its members has been consistent in all its operations since the 1890s. Its particular nature has responded to changing needs and interests, with the result that YMCA recreation has always been topical and popular. From its gymnasium classes in the nineteenth century, through the first camps in the late 1910s, and on to the expansions and diversifications of the post-World War II years, the YMCA has reflected wider social changes in recreation choices to remain a relevant and popular physical recreation provider for the local community.

Page 28

MISSION STATEMENT

Building on the international heritage of Christian Action and believing in the infinite capacity of people to grow and change when they are treated with trust, love and respect.

The Mission of the YMCA in Hawke’s Bay is the development of people towards the fullness of their potential, through the creation of special programmes, towards a community based on diversity, equality and service.

BICULTURAL STATEMENT

In New Zealand the YMCA:

– Recognises that the Treaty of Waitangi is the founding document of New Zealand.

– Agrees that New Zealand is a bicultural country with a multi ethnic society and that acknowledging biculturalism is to accept a willingness to share power and resources on a fair and just basis.

The YMCA in Hawke’s Bay endorses the National YMCA statements and further:

– Seeks to have on the Board and staff a balance of Maori and Pakeha that reflects the local community and the people it serves.

– Encourage each person to acknowledge their own uniqueness and appreciate the uniqueness of others.

(YMCA of Hawke’s Bay 1995)

Page 29

Chapter Two – The Mind

“I don’t think anyone ever stops wanting to learn whatever their age.”

– Jill Rhodes, founding member of Hawke’s Bay U3A.

In addition to the physical development of YMCA members, the Hawke’s Bay YMCAs have also maintained a consistent interest in members’ mental stimulation and development. As with physical programmes, YMCA courses have been adapted to meet the particular educational requirements of the local community. In the nineteenth century, this meant supplying reading material and newspapers to members; in later years the community needed more specialised knowledge, and since the early 1980s the Hawke’s Bay YMCA has focused on the education of people for specific vocations and employment.

From its first opening in 1890, the Napier YMCA reserved a room in its premises for reading and study to “afford instruction and enjoyment to the young men”. Members donated books, periodicals and newspapers to form a library, and the YMCA committee subscribed to British periodicals on behalf of the library. The YMCA reading room was a useful source of books and reading material for Napier people; British periodicals in particular were much sought after by colonists for their news of Home, and ready access to them at the YMCA would have been considered valuable.

At the turn of the century, Hastings youth had only limited educational facilities available to them, and as a result the Hastings YMCA provided a source of training and education. Napier was considerably better off, with both public and private high schools, but Hastings had only a technical secondary school in the area, and demand for this type of education was low. For much of the 1910s, then, the Hastings YMCA taught night classes in commercial subjects such as book-keeping, shorthand and clerical duties from its Station Street rooms. The first tutors were local men H.E. Stanton, T. Atkinson, T.H. Gill and Mr Sheffield. Mental stimulation was also provided in the form of literary and debating clubs, and a “mock parliament” group.

Following World War I these classes were in even greater demand, as returned servicemen needed retraining to re-enter the workforce. YMCA Huts were constructed in 1919 at both Napier and Hastings Hospitals for outpatients of the Soldiers Wards, and a range of lessons were taught there. Trades such as bootmaking, wool-cleaning and carpentry were offered in addition to commercial subjects, and crafts such as basketry and leatherwork. In the first four months of the Huts’ operations 125 soldiers passed through its doors. From 1921 a Repatriation Farm at Tauherenikau trained up to forty war veterans in agricultural work.

Vocational guidance work was first trialled by the Hastings YMCA in the late 1920s. Lectures were delivered to high school classes in an attempt to give boys

Page 30

some knowledge of different careers. The 1930 programme of lectures each attracted one hundred students, and included electrical engineer Mr J.H. Scott, accountant Mr V. A. Thompson, and orchardist Ralph Paynter. These lectures were particularly valuable to students as career counselling was unknown at this time, and most young people followed their parents’ advice or direction into “suitable” work.

The post-World War II rebirth of the Hawke’s Bay YMCAs occurred at a time of national prosperity and full employment, and social and recreational programmes were in far greater demand than educational classes. However, by the 1970s times had changed and vocational education and training were increasingly important community needs for the YMCA to meet. Napier responded to these needs with unconventional but successful education programmes. In Hastings, the town’s early 1980s unemployment rate was the highest in the country, and the area reported the second lowest response rate to training courses. The Hastings YMCA took up the challenge to train these unemployed, and taught Government-funded courses on a contract or sometimes pilot basis, as well as initiating programmes specifically tailored to the needs of Hawke’s Bay job-seekers.

The Downtown Y drop-in centre in Napier, although established in 1971 as a youth centre, also developed an alternative education programme for its youth in the 1970s. Many of the youth going to the Downtown Y had behavioural problems and were either failing school or not attending at all, and some had been placed in borstal. Pat Magill and the Downtown Y committee, with the agreement of the Social Welfare Department, decided to offer these youth an alternative learning environment more suited to their needs. Two school teachers, Mr and Mrs Titchener, from Hiliary College in Auckland were hired to teach students, and classes began at the Downtown Y in 1974. Lessons were designed to interest and stimulate the students, develop confidence, teach skills and strengthen their identified abilities. Maths, for example, was taught by playing darts. Other classes included reading, spelling, typing, art, speech, physical co-ordination, sewing, hygiene and personal appearance, shopping and budgeting. Craft classes were also held, as a report submitted to the local Education Department Inspector by the Titcheners in August 1974 described:

Activities at the workshop-school have varied according to individual students but all have been involved in making mats, cushions and oven-mitts with materials supplied through Mr Magill’s furnishing business. This common activity is of social value in giving unity to the group which has grown to about five students. The craft nature of the work is relaxing and confidence developing and gives the group an opportunity to contribute to the workshop-school’s finances. Students were also given help with job-seeking skills and helped into jobs when they were prepared. After twelve months the classes were proving highly successful, and the Minister of Education, Phil Amos, and the Minister of Maori

Page 31

Affairs, Matiu Rata, were invited to visit in July 1974. Both officials were impressed with the progress and performance of students, and had the students filmed at work. The curriculum and style of teaching of the unit was also incorporated into the state education system on a trial basis. In 1974 the school was renamed the Napier Community Activities Centre, and was taught by Marian Tait and later Judie Booth. Around 1980 the school was shifted to Napier Boys’ High School, and in 1995 operates as the Napier Community High School, catering for dysfunctional and problem boys.

The Napier YMCA also branched into cultural education courses in the 1970s. As increasing numbers of rural Maori moved into towns and cities, their contact with marae life and culture disappeared. For many Maori, it became difficult to continue practicing their culture and language, and classes such as those at the Napier YMCA were a successful alternative to marae-based lessons. Te Rina Sullivan-Meads tutored a junior Maori culture class on Maori mythology and waiata, while Tui Cunningham led a senior group. Sam Paenga coached a men’s haka class, and M. Waapu and A. Nuku taught Maori craft. This latter group produced kowhaiwhai for the Matahiwi meeting house, taniko belts and feathered bags. These classes were popular during the late 1970s, attracting up to 35 members each, but appear to have declined and disappeared in the 1980s.

From the 1980s Hawke’s Bay YMCA education programmes have been run on a contract basis with Government agencies such as the Regional Employment Advisory Council (REAC) and the Education and Training Support Agency (ETSA). As Government personnel and priorities alter, these courses have changed in both their title and goal. The first work schemes such as PEP were superseded by the skills-based programmes Steps and Tracks, followed by Tap, Access and Tops. These changes have generally been accompanied by an increase in government demands for planning, paperwork, documentation and bureaucratic procedures, and trainers now spend much of their time on administration. While some courses have survived these changes and continued to operate regardless, others have come to an end due to changing government requirements and community needs.

The earliest courses, PEP, TEP, YPTP aned the Work Skills Development Programme, were run with the Department of Labour and focused on providing work opportunities for youth. Those on the schemes were most often engaged in general labouring work, such as digging ditches and painting fences, including some work establishing the Hastings YMCA’s Maraekakaho orchard. This was work which kept people occupied, but didn’t necessarily help them develop marketable workskills. In an attempt to provide more skills-based training and employment preparation, the STEPS (School leavers’ Training and Employment Preparation Scheme) programme for 15-16 year olds was initiated in the early 1980s. The pilot programme was run at Hastings YMCA by a staff of six for forty participants. The course involved a series of training modules such as Home Management,

Page 32

Woodwork, Communication, Career Selection and Bushcraft. The course exceeded all expectations and was acknowledged by the Government as a “model scheme”. In the twelve months to May 1984, 98% of the 105 trainees who went through the Steps programme had no school qualifications. The success of the course is proven by the fact that 53% of these trainees found employment within two months of finishing the course. Steps continued through the mid-1980s as an extremely popular course, with up to 80 young people participating in the course each year. In 1985, the Pathways life skills course began operating at the Hastings YMCA. The programme, initially run by Shelley Oliver, focused on enhancing life skills and work readiness and aimed to develop participants’ “confidence and a belief in their worthiness within a positive climate for learning”. Modules in driving lessons, outdoor pursuits, mechanical skills, literacy and job search skills were taught, and in 1992 a group called Awhina-Koka-Tamariki was formed to teach parenting skills. The group, of about twenty young mothers, has sessions in childbirth education, dealing with Social Welfare, Plunket clinic visits, and general motherhood and parenting education. Trainees have always been encouraged to set goals and work toward them, no matter how difficult they might at first appear; a Herald-Tribune article in March 1987 reports a trainee who told her supervisor:

I’d love to be a pop singer, in black leather and high heels, but it’s only a dream. It could never be. But the trainer told her charge that if she “wanted a pop singing career to out and get it”. The trainee did just that. She organised guitar and singing lessons and is now on the way to acquiring the necessary career skills.

In addition to running these courses on government contracts, the Hastings YMCA also took an active role in developing a skill-based training course for the government, called Tracks. A National YMCA team designed the programme, pointing out that

Where jobs are available current employment programmes often have little relevance and are frequently unrelated to the local job market. This is, in part, due to a lack of research based planning and lack of consultation with employers.

Therefore Tracks aimed to develop skills which had been identified by local employers and unions as necessary for employment in the local industry. Job market research was to be carried out in each locality to identify growth industries for training, and local industry representatives were to be consulted in the planning of the training units. Hastings YMCA ran the pilot scheme for the Tracks programme in 1985-86, and taught sixty trainees in units of Horticulture, Hospitality, Construction and Forestry. Trainers and supervisors were supported by a committee of employer, union and YMCA Board representatives, and a Local Standards Advisory Group, and co-ordinated by Programme Manager Ron Sharp. The course was open-ended, and trainees could leave whenever they had learnt the necessary

Page 33

skills, and move on to work-based training. The first full year of the programme saw 162 trainees pass through, 68.5% of whom secured jobs or further training on completion of the course. Tracks was later adopted as a national programme, although the role of Hastings YMCA in developing the course to this level was not always acknowledged by government agencies.

Despite several name and administrative changes, some Tracks and Steps courses have continued to be taught by the YMCAs in Hawke’s Bay in a relatively similar form. The Hospitality Unit has experienced fluctuations in programme content, location and trainee numbers, yet has continued to produce high calibre graduates with a high rate of post-training employment. Cyril Whitaker, chair of the Hospitality unit committee, reported in 1988 that of all the unit’s success stories, the “biggest success is Tonto who came to us from 10 years at Whakatu and who is now a full-time barperson at the Mayfair Motor Inn.” Melanie Jacobs, a graduate of the Bar Services course, became in 1992, New Zealand’s first certified woman Cellar Master. The unit first operated from Michael’s Place in Napier, then from a coffee shop in Flaxmere and since 1988, from Rainbow Cottage in Eastbourne Street, Hastings. In 1995 YMCA Hospitality training was extended to Wairoa, where tutor Colleen Sullivan opened the Rainbow Cafe.

The Horticulture Unit has operated from Maraekakaho since 1982, when the proceeds of Hastings’ stadium sale were redistributed to new projects. The Hastings YMCA purchased 28 hectares of land on Highway 50 at Maraekakaho and seconded community worker Wally Hunt from the Hawke’s Bay Community College for six months to establish the orchard. PEP workers planted shelter belts, laid irrigation pipes, cleared land and generally prepared the section for its first intake of trainees. The project attracted some criticism from local fruit growers who predicted that the competition of a low-budget orchard would “disrupt normal market forces” and force local growers out of business, despite the comparatively small quantity of produce expected from the land. Nevertheless, the Rural Training Centre received approval first from the Hawke’s Bay County Council and the Department of Labour, and later from REAC and ETSA, and has run horticulture, orchard and farm skills courses for over ten years. In this time the Unit has received National Certification, diversified into crops such as asparagus and herbs, exported produce to Japan and in 1995 prepared a proposal for a viticulture course. The emphasis of the training courses is on encouraging a sense of responsibility in the trainees; the orchard is divided into four farmlets, with five trainees pooling their knowledge to work together on each section of land. Two stories typical of the Rural Training Centre’s outcomes were reported in the Herald-Tribune in January 1986:

Raewyn Hill is rapt with the job opportunity the programme has given her. . . She is on a six-week trial employment with a nursery in Havelock North. “It’s really good and I’ve learnt heaps in the weeks I’ve been here,” she said. “I knew a little but they’ve taught me propagating and picking

Page 34

and planting methods.” Another trainee, Graeme Tekuru, also 16, spent six months learning basic horticultural techniques under Tracks. He now has a job with an orchard in Hastings. ”I like the job… The orchard here is helping me.”

The Te Rito programme, which began in the early 1980s, operates in an expanded form in 1995. Napier youth workers Mo Ropitini and Toro Waaka developed a twelve-week course in the 1980s, which covered life and work skills including personal development, leadership skills, work readiness, first aid, driving, and budgetting [budgeting].

In 1994 this curriculum was expanded to a twenty four-week course including sexual harassment, cultural identity and discrimination and stress management. The course caters for up to twelve at-risk youths, usually aged sixteen or seventeen years, and aims to prepare trainees to undertake further, more specialised training.

The YMCA Literacy and Numeracy programme has also run continuously since the Association first began offering training courses. Individual tutoring is available to all trainees in all courses, and follows the philosophy of South American literacy trainer Paulo Freire. Rather than using the same programme with all trainees, each trainee is taught words and sentences around a topic of personal interest to them, whether it be motorcycles, gardening, or surfing. Classes include word games, puzzles, “Trivial Pursuits”-type board games, and crossword exercises. The programme occasionally produces “miracle” students, as Dennis Oliver

Photo caption – Trainees at the Hastings YMCA Rural Training Centre display their handiwork – a sprayer for use at the training orchard, built in September 1986. Left to right: Dave Whitfield, Anzac Hawkins, Paul Trower and Mike Prebble. – Photograph courtesy of Daily Telegraph.

Page 35

describes them: “it’s quite marvellous – the whole world opens up for them.”

Some YMCA training courses, however, have been more transient in their operations as needs and requirements shift. Napier YMCA taught a sales and marketing course briefly until its contract was not renewed in 1992. The Hastings YMCA’s Forestry Unit, established in 1986, ceased to operate in 1991, partly as a result of an unstable industry. A Construction course to train people as building labourers was set up in 1985 at Ruahapia Marae, and from 1988 House Maintenance and Child Care courses were run at Waipatu Marae. In January 1990, Waipatu Marae decided to manage the courses themselves, independent of the YMCA. Since 1991, the YMCA has intermittently run Conservation Corps projects with the Department of Conservation and the Ministry of Youth Affairs. Each course takes ten people, and teaches job search and recreation skills as well as completing a major environmental project. Past projects have included the construction of a footbridge and boardwalk at Tongoio [Tangoio], the eradication of noxious weeds from the Maraetotara Valley, and improvements to Riverland Park. Future plans for Conservation Corps projects include the construction of a firebreak around Camp Opoutama and a fish sampling scheme.